Kent Coast Sea Fishing Compendium |

East Kent Inshore Wreck Table |

There are three common formats for writing degrees, all of them appearing in the same latitude-longitude order:

| DMS | Degrees: Minutes: Seconds | 51° 14' 05" N | 1° 24' 12" E |

| DM | Degrees: Decimal Minutes | 51° 14.083 | 1° 24.2 |

| DD | Decimal Degrees (generally with 4-6 decimal numbers) | 51.234722° | 1.403425° |

DMS is the most common format, and is standard on all charts and maps, as well as GPS and geographic information systems (GIS).

DD is the most convenient if a need for calculation or computation might arise, avoiding the complexity and likely introduction of errors by mixed radix degree minute second arithmetic.

A degree of latitude is approximately 69 miles, and a minute of latitude is approximately 1.15 miles. A second of latitude is approximately 0.02 miles, or just over 100 feet. A degree of longitude varies in size. At the equator, it is approximately 69 miles, the same size as a degree of latitude. The size gradually decreases to zero as the meridians converge at the poles. At a latitude of 45 degrees, a degree of longitude is approximately 49 miles. Because a degree of longitude varies in size, minutes and seconds of longitude also vary, decreasing in size towards the poles.

There are several formats for writing degrees, all of them appearing in the same latitude-longitude order:

DMS: Degrees:Minutes:Seconds (49° 30' 00"N, 123° 30' 00"W)

DM: Degrees:Decimal Minutes (49° 30.0', -123° 30.0'), (49d 30.0m,-123d 30.0')

DD: Decimal Degrees (49.5000°,-123.5000°), generally with 4-6 decimal numbers.

DMS is the most common format, and is standard on all charts and maps, as well as GPS and geographic information systems (GIS). DD is the most convenient if a need for calculation or computation might arise, avoiding the complexity and likely introduction of errors by mixed radix degree minute second arithmetic. A DMS value is converted to decimal degrees using the formula (D + M/60 + S/3600).

How To Convert Decimal Degrees (DD) to Degrees Minutes Seconds (DMS)

- The whole units of degrees will remain the same (i.e. in 121.135° longitude, start with 121°).

- Multiply the decimal by 60 (i.e. .135 * 60 = 8.1).

- The whole number becomes the minutes (8').

- Take the remaining decimal and multiply by 60. (i.e. .1 * 60 = 6).

- The resulting number becomes the seconds (6"). Seconds can remain as a decimal.

- Take your three sets of numbers and put them together, using the symbols for degrees (°), minutes ('), and seconds (") (i.e. 121° 8' 6" longitude)

Click here to convert Decimal Degrees (DD) to Degrees, Minutes, Seconds (DMS)

How To Convert Degrees: Decimal Minutes (DM) to Decimal Degrees (DD)

Decimal Minutes (DM) values are converted to Decimal Degrees (DD) by dividing the DM minutes and seconds by 60 e.g. for 51.28.527 divide 28.527 by 60 to give 0.47545 and add that decimal value to the degrees: 51.47545

|

A DMS value is converted to DD using the formula |

D | + | M | + | S |

| 60 | 3600 |

| 51 + | 14 | + | 05 |

| 60 | 3600 |

| 51 | + 0.233333 | + 0.001388 | = 51.234722 |

A DD value is converted to DMS as follows:

- the whole units of degrees will remain the same (i.e. in 51.234722 latitude, start with 51)

- multiply the decimal by 60 (i.e. 0.234722 x 60 = 14.08332)

- the whole number becomes the minutes (14')

- take the remaining decimal and multiply by 60 (i.e. 0.08332 x 60 = 5)

- the resulting number becomes the seconds (5")

- take your three sets of numbers and put them together, using the symbols for degrees (°), minutes (') and seconds (") (i.e. 51° 14' 05" latitude)

How to convert Degrees Minutes Seconds (DMS) to Decimal Degrees (DD)

Click here to convert degrees, minutes, seconds (DMS) to decimal degrees (DD).

Wrecks and Aircraft Crash Sites at Sea in Dover District

Summary

The Strait of Dover is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the World. The Channel has seen the arrival of invasion fleets and raiding vessels and has been the scene of many naval conflicts. In times of peace it has acted as an important trade route, both for vessels visiting the District's ports as well as those passing by on route to other designations across the globe. Off the coast of Deal lies The Downs, an important naval anchorage that has acted as a place of refuge for many vessels over the centuries. The business of the Channel along with the presence of the hazardous Goodwin Sand Banks has resulted in an immense number of wrecks off the District's coastline. The Channel also acted as a frontline during the aerial conflicts of the Second World War, with numerous aircraft shot down over the Channel during the Battle of Britain.

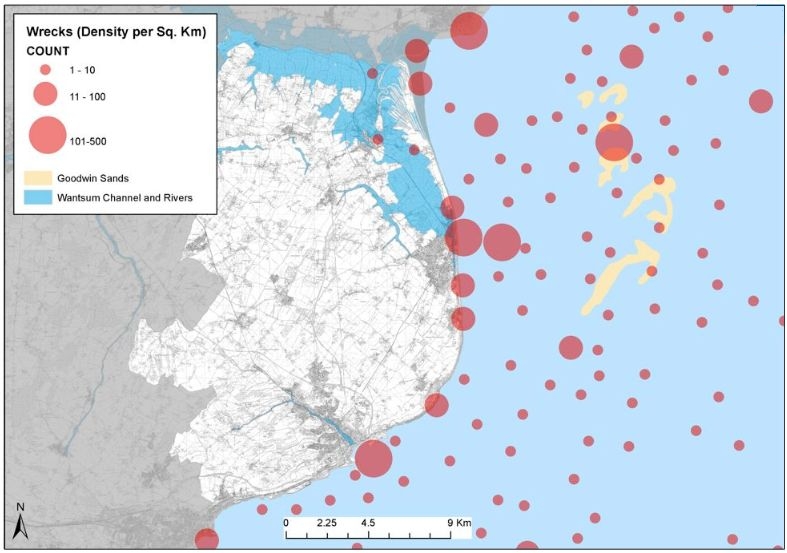

Wreck sites per square kilometre as recorded on the Kent Historic Environment Record

Introduction

As recent as 15,000 years ago much of the North Sea and the English Channel was part of the continental land mass. As sea levels rose following the last ice age this land mass became submerged beneath the growing Channel and North Sea retreating to a land mass which bridged between Britain and the continent from what is now East Kent and East Anglia. Around 6000 BC the connection with the continental landmass was finally breached creating the Dover Strait and the island we live in today.

With Dover being the closest point to continental Europe and commanding the southern shores of the narrow Strait, the history of the District has been inexorably linked with the maritime use of the Strait ever since. Forming the link between the North Sea and the English Channel, the Strait of Dover has become one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. Vessels passing between the north countries and southern Europe and beyond would often use the sheltered waters of the Channel rather than risk the more hazardous Atlantic passages. As the shortest crossing point between Britain and the continent the Strait has been used for cross-Channel travel since prehistoric times. Great Roman ports of entry developed at Richborough and Dover and later the ports of Dover, Sandwich and Deal became prominent in the nations maritime and naval history.

As well as being a conduit, the sea between the District and the continent has also formed a barrier and the first line of defence against invading armies. The coastal waters of Dover District have seen the arrival of invasion forces, many raids on the coast and ports, and numerous naval engagements from Roman times to the Second World War. All of this, coupled with the natural dangers to shipping and the presence of the hazardous Goodwin Sands off the east coast of Deal have resulted in an immense number of wrecks in the District's coastal waters.

As well as naval engagement, the war in the air, particularly in the Second World War extended over the Channel. Many Allied and German aircraft were shot down and the remains of their wrecked aircraft can be found in the District's coastal waters. Although not strictly maritime in their nature, these sites will be described and discussed below.

The Goodwin Sands and The Downs

The Goodwin Sands is an extensive line of sand banks which lie approximately four miles off shore east of Deal. The sand banks which are around nine miles in length have long been a major navigational hazard to shipping in this narrow historically important sea route and the scene of many a shipwreck leading to the Goodwins becoming known as 'The Shyppe Swallower'.

As well as presenting a hazard, the Goodwin Sands also provided a relatively sheltered anchorage known as The Downs for shipping in times of bad weather or as they waited for the favourable conditions to round the North or South Foreland. The Downs became a strategically important naval anchorage and by the sixteenth century was protected by the artillery forts at Deal, Walmer and Sandown. The subsequent development of the towns of Deal and Walmer owes much to the importance of the anchorage and the need to service and provision the ships that lay there.

More than 1,000 shipwrecks have been recorded on the Goodwin Sands since the first in 1298 though the true toll is likely to be far greater. One of the most tragic events in the history of the sands was the Great Storm of 1703. The hurricane which ripped through the country in November 1703 wrecked six naval vessels and numerous merchantmen on the Sands. Amongst these were the third rate ships of the line HMS Stirling Castle, HMS Northumberland and HMS Restoration and the fourth rate HMS Mary. In all more than 1,500 seamen are estimated to have drowned nationally during the Great Storm, with around 1,190 lives being lost on the Goodwin Sands despite the efforts of the Deal boatmen who rescued over 200 souls. While many wrecked ships have been fully swallowed by the sands, the masts of a number of twentieth century wrecks can be seen at low water. The shifting nature of the sands has caused the remains of wrecks to be exposed. In 1979 divers found the remains of HMS Stirling Castle, which had been revealed following a large shift in the sands. Subsequent diving on the wreck, which has deteriorated since its exposure, has resulted in a number of objects being recovered and these were put on display in the Ramsgate Maritime Museum prior to its closure in 2009.

| On Saturday, 27th November 1703 the Mary (originally built as the Speaker in 1649) was lost on the Goodwin Sands. 272 men and Rear-Admiral Beaumont were drowned. Her captain, Edward Hopson, and the ship's purser were both ashore at the time. The sole survivor, seaman Thomas Atkins, was thrown from the deck of the Mary as it floundered and broke up and, whilst in the water clinging to a piece of timber, saw Rear-Admiral Beaumont leave the ship's quarterdeck and drown. A freak wave then flung Atkins onto the upper deck of the Stirling Castle. Minutes later, as the Stirling Castle became wrecked and Atkins was shipwrecked for a second time, he was again thrown into the waves but again had a huge slice of luck as he was washed into the only lifeboat to have broken adrift from the Stirling Castle and eventually beached on the Kent coast and survived despite suffering from exposure. |

Over three centuries later, that storm is still considered the greatest storm to ever strike Britain in recorded history. Some historians argue that the storm lead to profound changes in Britain's social and industrial structure. It also spawned one of the earliest books written solely on a weather event - "The Storm" - the first published work of Daniel Defoe which tells the story of the thirteen Royal Navy ships lost and the 1,500 sailors drowned.

Wrecks

The Kent Historic Environment Record records around 1,500 known wrecks or the sites where vessels have reportedly foundered within 15 kilometres of the District's coastline. Many of these have been broken up by time and tide along with direct clearance efforts carried out more recently. Despite this, a great many survive as buried or part-buried maritime archaeological sites and some are even visible depending on tides.

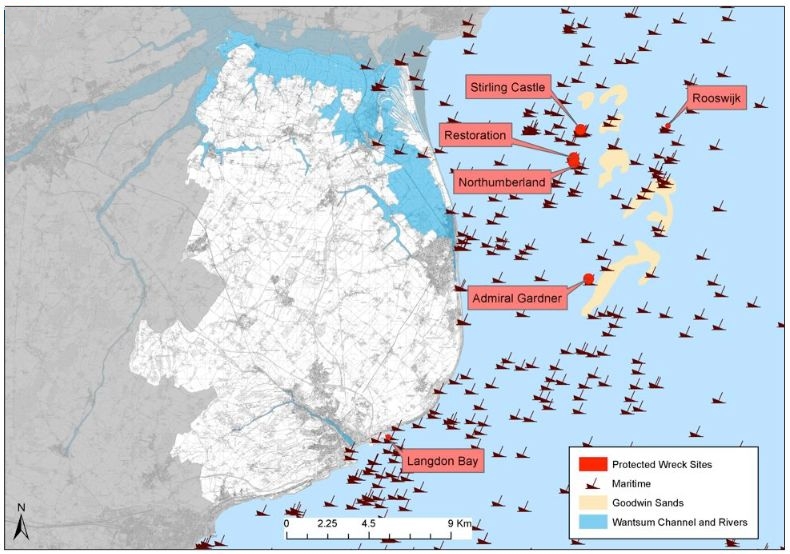

Protected Wreck Sites

A number of wrecks, recognised as being of historical, archaeological or artistic importance are designated through the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973 to prevent uncontrolled interference with their remains. The Act defines a restricted area where it is an offence to tamper with, damage or remove any part of the wreck or associated objects, carry out unlicensed diving or salvage activities or to drop materials on to the wreck or the restricted area from above. There are six Protected Wreck Sites off the Dover District coastline whilst a seventh, an unnamed wreck coded Goodwins and Downs 8 (GAD8), was being considered for protection in 2012.

The earliest known wreck and a Protected Wreck Site is the site of a Bronze Age wreck at Langdon Bay dating to around 1100 BC. The site was discovered by divers from the Dover Sub-Aqua Club in 1974 who noticed a number of bronze objects on the sea floor. Nothing of the structure of the vessel has been found but to date over 360 bronze objects have been systematically recovered from the sea floor. The objects include tools, weapons and ornaments of a type that are made in France and rarely found in Britain. Current interpretation is that the site represents the remains of a vessel carrying a cargo of scrap metal from France to Britain, implying cross channel trade and exchange in the Middle Bronze Age.

Three of the Protected Wreck Sites lying on the Goodwin Sands are the remains of the three Third Rate ships of the Royal Navy - HMS Stirling Castle, HMS Restoration and HMS Northumberland - lost during The Great Storm of 1703. The three vessels form an important group of vessels which representing a historical event of national significance, are a valuable archaeological resource that can help to illustrate warship technology and way of life in the Royal Navy of the late seventeenth to early eighteenth centuries.

Wrecks and Protected Wreck Sites as recorded on the Kent Historic Environment Record.

Note: each wreck symbol may represent numerous reports and are the location of foundering as well as wrecks.

HMS Stirling Castle, Restoration and Northumberland were all 70-gun ships of the line that had been built in 1678-9 as part of Samuel Pepys' regeneration of the English navy. The Stirling Castle was built at Deptford while the Northumberland was significantly the first Third Rate ship built under contract after it was realised that the naval dockyards could not cope with the production of the number of ships that Pepys requested. All three ships were re-built and refitted at Chatham from 1699 to 1701. Part of a returning squadron from the Mediterranean, the three ships anchored in the shelter of The Downs to escape the storm but were swept on to the Goodwin Sands along with many other vessels. Overall 1,190 lives were lost on the Goodwin Sands during The Great Storm.

All three wrecks lie in around 15 to 20 metres of water. HMS Stirling Castle was found by divers from Thanet in 1979 after the ship had been exposed by shifts in the Goodwin Sands. The exposed hull was seen to be in remarkably good condition and the divers recovered many objects that were at risk of being lost in the sands. The site was purchased by the Thanet Archaeological Unit (now the Trust for Thanet Archaeology) but the site became lost in the sands until it began to re-emerge in 1998. The ship was surveyed in 1999 and found to have undergone substantial movement and internal collapse since its original discovery. As the ship has become exposed a large number of artefacts considered to be at risk have been recovered. These include both organic and inorganic artefacts that have survived to a high level of preservation. Artefacts recovered have included guns and their carriages, navigational equipment, anchors, rigging elements and ropes, a unique intact Stuart copper galley kettle, a medical box and many personal items including book covers. The wreck has been identified by the recovery of a ship's bell marked with the naval arrow and '1701' and initials on pewter objects. Some of the items are on display at the National Maritime Museum and others were housed in the former Ramsgate Maritime Museum.

The site of HMS Northumberland was discovered in 1980 as part of a systematic investigation of fishing net fastens. The wreck site consists of scattered mounds of debris and some pieces of large ship structure. Divers made an initial survey and recovered numerous portable objects including coils of anchor cable, ordnance, copper cauldrons, a box of musket shot and like the Stirling Castle a ship's bell marked with the naval arrow and date '1701'. Detailed surveys, including geophysical survey, were carried out of the site between 1993 and 1998 and more recently in 2002. Currently the site appears to be relatively stable though items are sometimes exposed by the shifting sands.

There is no definitive evidence that the third Protected Wreck Site is that of HMS Restoration although it seems likely. The site consists of two debris mounds and it is unclear whether these are from a single vessel or from two. It is possible that they may be parts of the Fourth Rate ship HMS Mary, sunk at the same time as the Restoration. The site was discovered during the fishing net fasteners survey in 1980 and although side scan sonar and magnetometer surveys have been carried out in recent years, the site has not been surveyed in detail. Material recorded on the sea bed includes large ships timbers, several cannon, an anchor and galley bricks. A bell reported to be from the Restoration was handed into Ramsgate Maritime Museum but without the arrow and stamped '1692' it may belong with the Mary.

The other Protected Wreck Sites are two merchant vessels, testifying to the post-medieval mercantile nature of much of the traffic in these waters. The first is the Rooswijk, a Dutch East Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie) built in 1737, which became stranded on the Goodwin Sands in 1740 while en route from Texel in the Netherlands to the East Indies. After several years of documentary research and a magnetometer survey ingots marked 'VOC' were recovered in 2004. A survey in 2006 found that the site consists of two (now three) main areas of wreckage. The timber hull and interior framework at the stern was found to be in remarkably good condition and groups of iron bars were observed sitting on timbers. The findings at the site of the Rooswijk indicate that large sections of the wreck are buried and preserved to a high degree.

Rooswijk

This site is designated under the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973 as it is or may prove to be the site of a vessel lying wrecked on or in the sea bed and, on account of the historical, archaeological or artistic importance of the vessel, or of any objects contained or formerly contained in it which may be lying on the sea bed in or near the wreck, it ought to be protected from unauthorised interference. Protected wreck sites are designated by Statutory Instrument. The following information has been extracted from the relevant Statutory Instrument.

- List Entry Number: 1000085

- Date first designated: 13th Januray 2007

- Statutory Instrument 2007/61

- Location Description: Kellet Gut, Goodwin Sands, off Deal, Kent

- Latitude: 51.27405000

- Longitude: 1.57561700

- National Grid Reference: TR4948758840

Summary of Site

The remains of a Dutch East Indiaman which foundered towards the north-eastern end of the Kellet Gut, after grounding on the Goodwin Sands, in 1739. At the time of loss she was bound from Amsterdam and the Texel to Jakarta with coin, bullion and a general cargo, including sheet copper, sabre blades and stone blocks, as well as passengers.

History

The Rooswijk is a vessel of the Dutch East Company (VOC) built in 1737 which stranded on the Goodwin Sands in 1739 while en route from the Texel to the East Indies. The vessel is described as a 'retourschip', a specific type of Dutch East Indiaman which was designed to withstand the lengthy voyages of 18 months to three years typically undertaken en route to Batavia (Indonesia). The site was found after several years of documentary research and following a magnetometer survey on the site.

Designation History

Designation Order: No 61, 2007 Made: 13th January 2007 Laid before Parliament: 17th January 2007 Coming into force: 9th February 2007 Protected area: 150 metres within 51 16.443 N 001 34.537 E. No part of the restricted area lies above the high-water mark of ordinary spring tides.

Documentary History

Built in 1737 in Amsterdam for the Amsterdam Chamber of the Dutch East India Company, the Rooswijk was lost on the Goodwin Sands one day out from the Texel on her second voyage to the Indies in January 1739. Her previous voyage had been to Batavia (Jakarta). The day following her departure from the Texel, the Rooswijk is recorded as being wrecked with all hands and troops. "A great many pieces of wreck and packets of letters, all directed to Batavia, have been taken up." Many pieces of wreckage were found floating in the Downs. There were numerous newspaper reports on her loss, including the London Written Letter: "We had this morning an account from Deal of a Dutch East India Ship outward bound, being ashore on the Goodwin Sands; and this afternoon it was reported to be lost, and all her crew." Contemporary newspapers record "the violent storm of wind, etc. which has held for two days past, has done considerable damage to shipping lying in the River (Thames) …"

It therefore appears from sources that the vessel was caught up initially in an easterly storm which afflicted the eastern coast of England from north to south. This would have driven her directly onto the Goodwin Sands on her outward-bound passage from Amsterdam, and the "contrary winds" mentioned in some sources would have caused her to shift on the sands. In turn this would have contributed to the ship breaking up rapidly, consistent with the wreckage and mail being all the clues left to her loss, together with the total loss of life. Doubtless, however, the severe cold also contributed to the total loss of the crew.

Prior to 1752, the New Year fell on 25th March. The date of loss therefore probably occurred circa 30 December 1739.

Archaeological History

A sport diver found the remains of the Rooswijk after extensive documentary research and magnetometer survey. The discovery was kept secret to enable the recovery of bullion. In December 2005, silver found aboard the wreck was handed over to the Netherlands Finance Minister, representing the Dutch Government as heirs to the Dutch East India Company, having taken the company over in 1798. Dutch archaeologists expressed regret that they had not been part of the salvage operation.

The seabed consists of fine-grained, mobile sand with broken shell. Some small patches of stones were observed in areas of scouring around upstanding wreck material. Small sand waves have been recorded in all areas searched, separated by small hollows.

The salvage of the Rooswijk prior to designation is believed to have recovered more than 1,000 artefacts including a musket stock; 2 musket side plates marked "VOC"; a musket trigger plate; two wooden chests and lids; 21 ebony knife handles; 2 concreted knives; a Mexican pillar dollar; 553 silver ingots marked "VOC"; a tobacco tin; a huntsman's sword hilt; a gilt sword hilt; a sword scabbard belt hook; part of a leather scabbard; a brass wine pot with a missing leg; a pistol stock; a cutlass handle; a cutlass scabbard; a copper alloy cauldron; and 3 stoneware vessels.

The floor timbers collapsed following the wreck and the contents of each deck fell on top of each other, reflecting the physical and social layers of shipboard life. The top layer therefore included items from the officers' dining room, including pewter dinner plates and a mustard pot, wine glasses, a copper cauldron, brass candlesticks and a box of eye glasses.

The silver bullion was also found in this area in 4 lb bars, having been mined in Mexico, and sold on to the Amsterdam Chamber of the VOC, whose imprint is on the bars of silver, for use in the coinage of Batavia.

The layer immediately underneath comprised the contents of the ship constable's cabin. As he was responsible for the maintenance of law and order on board, 50 muskets were found in the area. Beneath this again was the vessel's 'cartridge locker' containing bar and round shot, while three cannon and a gun port were located in an area thought to represent part of the gun deck.

A pair of Frechen mugs, dated 1550 - 1600, was located within the site and represented an anomaly, possibly indicating that there is wreckage from more than one vessel on this site, although it could be that, owing to their robust nature and widespread use, they were still in use on a vessel such as the Rooswijk in 1739.

The Maritime Museum in Vlissingen will house objects recovered from this wreck and handed over to the Dutch.

The final Protected Wreck Site is that of the Admiral Gardner. An 800 ton East Indiaman, built in 1797, the Admiral Gardner was wrecked on the Goodwin Sands during a gale in 1809. Bound for Madras with a mixed cargo of anchors, chain, guns, shot and iron bars, she also carried 48 tons of copper tokens to be used as currency by the East India Company.

The site of the wreck was first noted when tokens were found in sand dredged from the Goodwins in 1976. The site was located in 1983 by divers investigating a fisherman's snag and subsequent salvage operations recovered over a million tokens. With concerns over the lack of archaeological standards being applied in the recovery, the site was designated in 1985, this was revoked in 1986 and it was re-designated in 1990. The wreck lies in an area of the sand banks which is highly mobile and an area of approximately 15 x 20 metres of wreckage mounded to 1 metre above the sea bed has been exposed. In a second area away from the main mound, two guns and an anchor have been found. At present the site is fairly stable though the traces of the salvage works can be seen in the wreckage. Visible on one of the cargo mounds of the wreck are iron stocks and anchors, ships timbers and a scatter of loose tokens. The ship remains vulnerable to unauthorised diving and the shifting sands.

The wrecks of the Rooswijk and the Admiral Gardner represent important archaeological evidence for the practice of large-scale commerce between Europe and Asia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They are good representative examples of the powerful ships that plied the trade to and from the Dutch and British colonies. In the case of the Admiral Gardner the cargo illustrates the wealth, influence and control the East India Company had in the Asian sub continent.

In 2010 Wessex Archaeology undertook diving investigations of a number of wreck sites west of the Goodwin Sands in the area of sea known as the Downs. Among the sites investigated was a wreck coded Goodwins and Downs 8 (GAD8). The diving investigations recorded a scatter of at least seven pieces of cast ordnance along with a substantial section of coherent structural timbers. Dating evidence suggests that the site represents the wreck of an armed wooden sailing vessel dating to between 1650 and 1750. It has been suggested that the wreck may represent the remains of the fourth rate British warship HMS Carlisle which accidentally exploded and sank in 1700, although this has not been confirmed. Ships and boats of this period are rare and survival of in situ pre-1750 ship material is rare nationally and the identification of intact timbers shows the site's archaeological potential. The Goodwins and Downs 8 (GAD8) wreck is currently being considered for protection as a protected wreck site and illustrates the potential for further significant wreck sites to be exposed on the Goodwin Sands or the Downs.

Merchant Shipping Act 1995 and Protection of Military Remains Act 1986

The vast majority of the wrecks lying offshore from the District are not safeguarded through the Protection of Wrecks Act 1973. Two other pieces of legislation which afford some protection to shipwrecks are the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 and the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986.

The Merchant Shipping Act 1995 requires that all wreck material that comes from UK territorial waters and any wreck that is landed in the UK from outside these waters must be declared to the Receiver of Wreck. Wreck is defined as anything which is found in or on the sea, or washed ashore or in tidal water that may have come from a shipwreck or vessel regardless of age or importance. Finders who report their finds to the receiver of Wreck have salvage rights.

The Protection of Military Remains Act 1986 deals with military remains of both aircraft and ships. All military aircraft are automatically designated under this legislation but shipwrecks are not. Vessels are not automatically designated but may be designated under this Act either as a 'Protected Place' or as a 'Controlled Site'. Divers may visit a Protected Place as long as they do not disturb the remains but are prohibited from visiting Controlled Sites. Designation as a 'Controlled Site' is only applicable to wrecks of less than 200 years age (since sinking) in UK waters and for 'Protected Places' vessels lost after the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. Wrecks designated as 'Protected Places' can include UK vessels outside UK Waters and foreign vessels lost within UK waters. The Ministry of Defence’s criteria for designation include:

- Whether the wreck represents the last resting place of servicemen;

- Whether the wreck has suffered disturbance and looting, and whether designation is likely to stop such disturbance;

- Whether diving on the wreck attracts public criticism; and

- Whether the wreck is of historical significance.

In addition wrecks that are considered dangerous are designated as 'Controlled Sites' as might be those wrecks designated as 'Protected Places' which suffer sustained disturbance.

The Ministry of Defence has been undertaking a rolling programme of designation since 2001. To date the wrecks of twelve vessels have been designated as 'Controlled Sites', none of which are in the District's offshore waters. Fifty Five wrecks have been designated as 'Protected Places', only one of which lies within the District's coastal waters, the German submarine U-12. U-12 was a Type II-B U-Boat built in 1935 and sunk near Dover on 8th October 1939 after striking a mine with the loss of all 27 of her crew. The exact position of the U-12 is not known but the wreck was nominated by the German government to be a 'Protected Place' as a representative of all others lost within UK jurisdiction.

Undesignated Wrecks at Sea

The overwhelming majority of the wrecks off the coast of Dover District are not covered by designation. As well as the recorded loss of individual ships and in some cases identified wreck sites, there are likely to be a vast number of other vessels which have been lost without specific record. With use of the offshore waters for coastal and cross channel navigation since prehistoric times and later as a conduit for longer sea voyages the remains of craft lost through the natural dangers of weather, navigation through the narrow strait and the hazardous sand banks of the Goodwins are likely to be found in the off-shore waters of the District. Occasionally large numbers of vessels have been recorded lost through major storm events such as The Great Storm in 1703 described above or that in 1624 when many ships and their crews perished in The Downs.

As well as the natural events, the waters off the shore of the District have been the scene of many documented raids, invasion and conflicts from Iron Age times to the twentieth century. In 55 BC, the coast in the region of Deal saw the arrival of a Roman expedition led by Julius Cæsar with more than a hundred vessels packed with troops and supplies. The Roman fleet beached or anchored (presumably in The Downs) was more suited to the conditions and tides of the Mediterranean than of the English Channel and many vessels were wrecked or rendered unseaworthy. Cæsar returned a year later with a fleet quoted by him to be of 800 vessels. Once again the ships were damaged at anchor in a storm and Cæsar was forced to salvage and repair his fleet. AD 43 saw the arrival at Richborough of a vast Roman invasion fleet under Aulus Plautius carrying four legions and a similar number of auxiliaries.

In the Roman period there is evidence of commercial traffic between the Kent coast and the Continent but no confirmed Roman wrecks are known in the waters of the District. Towards the end of the Roman period the coast was subjected to coastal raids by North Germanic tribes and this saw increased activity by the Roman navy (the Classis Britannica) that had bases at Dover and Richborough. Wrecks relating to this military activity may await discovery. The Anglo-Saxon chronicles hint at the arrival of invaders and settlers immediately following the withdrawal of Roman rule and record ninth century raids by Vikings along the East Kent coast and a number of sea battles between the Anglo Saxons and Vikings off the coast of Sandwich in AD 851, 853 and 885.

Naval conflicts off the District's coastline continued into the medieval period. On 24th August 1217 the naval Battle of Sandwich saw an English Plantagenet English fleet commanded by Hubert de Burgh sally from Sandwich and attack a Capetian French armada of eleven troop ships and seventy other vessels. The armada, under the command of Eustace the Monk and Robert de Courtney, was intended to supply the forces of Prince Louis of France who held London at the time. The English took the flagship and leaders and most of the supply vessels. Only nine troop ships and six supply vessels managed to gain refuge at Calais.

The fifteenth century saw raiding by the French on the Dover coastline which culminated in the burning of Sandwich in 1457. In January 1460 a naval skirmish during the War of the Roses also known as the Battle of Sandwich saw the Yorkist Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick defeat and disperse a Lancastrian fleet.

21st October 1639 saw the Battle of the Downs during the Eighty Years War or the Dutch War of Independence from Spanish rule. With overland routes blocked by the French, the Spanish sent a fleet of an estimated 74 ships to relieve and supply their last foothold in Flanders at Dunkirk. After a short battle with an inferior Dutch fleet off Calais, much of the Spanish fleet took refuge in The Downs under English neutrality. Initially blockaded by the Dutch, the Spanish were attacked by an overwhelming force led by Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp and decisively beaten. There are conflicting estimates on the losses by the Spanish though it seems that a number of ships ran aground on the Goodwin Sands of which some were later refloated, but others were burnt, sunk or captured.

The frustration of the English navy in being unable to intervene in the flagrant violation of their neutrality caused a lingering resentment that may have contributed to the outbreak of the Anglo-Dutch Wars later in the century. On 19th May 1652 (29th May 1652 Gregorian calendar), the first naval engagement of the war took place off the Dover coastline and was known as the Battle of Goodwin Sands. Here a Dutch convoy with forty escorts under the command of Admiral Maarten Tromp refused to dip their flag to a fleet of 25 English vessels under Robert Blake as had been required by Cromwell of foreign vessels using the Channel. Warning shots were exchanged with casualties and then a full five hour battle broke out. The English gained a narrow victory capturing two Dutch vessels one of which later sank.

Many of the vessels lost in the waters off the District's coastline date from the First and Second World Wars. The Dover Strait was an important line of defence preventing German naval craft entering the English Channel in the First World War. This line of defence was maintained by the Royal Navy's Dover Patrol which operated from both Dover and Dunkirk and was involved in many skirmishes. Perhaps the most significant engagement was that of the Battle of Dover Strait in 1916 when on 26–27th October 1916 flotillas of German torpedo boats based in Flanders attacked the Dover mine barrage and destroyed several naval drifters, a destroyer and damaged several others.

The Second World War saw the Strait of Dover and the English Channel as the first line of defence between Britain and occupied Europe. Dover played a key role in the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from 26th May to 3rd June 1940 from Dunkirk receiving over 200,000 of the evacuated personnel and overseeing command of Operation Dynamo from the tunnels beneath the White Cliffs. In 1940 the Battle of Britain raged over the District's coast. Many ships were lost during the war due to bombing, striking mines or from attack by U Boats. A number of U Boats themselves were also lost in the Strait including three which hit mines in quick succession in 1939.

The wrecking of ships, particularly on the Goodwin Sands, has continued since the Second World War. In 1954 the South Sand lightship was lost with seven crew members. The sister ships Luray Victory and the North Eastern Victory were both lost on the Goodwin Sands in 1946 and were notable as they were not swallowed by the sand and their masts remain visible to the present. In 1991 the MV Ross Revenge used by the pirate radio station Radio Caroline was salvaged from the Goodwin Sands. This link to Pathe news footage illustrates the grounding of the Italian steamer Sylvia Onorato in 1948.

Wrecks on land

As well as wrecks at sea, other wrecks may be found on land which has since been reclaimed from the sea. The Wantsum Channel was an important navigable sea route until medieval times and is likely to have ancient wrecks amongst its buried archaeological assets. A dug-out canoe was discovered within the silts of the Wantsum during sewer trenching through the marshland near Great Downs Bridge, just to the east of Sandwich, in April 1936. The craft is reported to have been taken to Sandwich for more detailed study but unfortunately it is never heard of again and nothing more is now known of it locally. Its date remains unknown - it could have been prehistoric, but it might equally well have been later.

In 1936 B.W. Pearce, a senior archaeologist excavating at Richborough, obtained an interesting report from one of his workmen. He recounted how in a gravel pit at Stonar the timbers of a 'Roman galley' had been found some years previously. The timbers were reported to have been preserved in waterlogged gravels and had seemingly been cut by an adze. Experts were said to have been brought in to view the vessel, but once they had left the workmen tried to drag out the remains with a crane, the result being that the vessel broke-up. The pieces were taken away but it is again not known what happened to them and the Roman date of this vessel cannot now be confirmed. Whatever the date it would seem that the remains at Stonar related to a vessel of some considerable size and antiquity. Other areas such as the Lydden Valley and the mouth of the Dour may also have buried wreck sites.

Hulks, etc

The District's archaeological remains will also include many vessels which have been abandoned and left to the elements as 'hulks'. The earliest known vessel of this type and one of the District's most notable heritage assets is the Dover Bronze Age Boat, found in the silts of the Dour estuary during construction works in 1992. The wreck was found six metres beneath Townwall Street in Dover during the construction of a subway. The discovery comprises more than half of a disassembled vessel, one of the most complete vessels of the period ever found and internationally important. While a large part of the boat was excavated and lifted to form the centrepiece of a gallery at Dover Museum, a substantial part of the boat was outside of the work's cofferdam and remains buried beneath Dover. The likelihood of similar boats surviving elsewhere in the Dour, Wantsum and Lydden Valley alluvium is strong.

Later hulks are also likely to survive in these alluvial deposits. Accounts of the two landings by Julius Cæsar refer to the wrecking, salvage and repair works to his fleet. The anchorages around the Roman port of Richborough and that at Dover, the medieval ports of Sandwich and Stonar are likely to be the focus of abandoned vessels. In Sandwich the rare remains of a late fourteenth century merchant vessel were found during sewer works in 1973. The Sandwich Boat as it has come to be referred to appears to have been laid up in a small creek to the east of the town walls and is an important example of a vessel of the period. The timbers from dismantled ships may have been reused in medieval buildings or in waterfronts in the historic coastal towns of the District.

In the First World War a great military port was established at Richborough in the mouth of the Stour to supply the Western Front. Special barges were constructed at the port to transport goods across the Channel to the canals that battlefields. Whether any traces of the boat building or vessels that used the port survive in the Stour has not been established. Perhaps the latest abandoned hulk in the District of any heritage significance can be found in Stonar Cut. Here a German 'Raumboot', a fast mine sweeping vessel dating to the Second World War was abandoned in the 1980s and can be seen mostly submerged in mud at low water.

Aircraft crash sites at sea

There are 47 known aircraft crash sites in the coastal waters of the District and there are likely to be many more which as yet have not been discovered. The majority of these sites date to the Second World War when both Allied and German forces incurred huge losses in the region during the Battle of Britain. One aircraft, a Dornier 17 shot down by fighters of No. 264 Squadron in August 1940, has recently been discovered in extremely good condition on the Goodwin Sands and is due to be raised for display in the RAF Museum at Cosford in spring 2012. The Dornier attempted a crash landing on the sand banks but flipped on landing killing two of its four man crew. The survivors were rescued.

All military aircraft crash sites as explained above are designated as 'Protected Places' under the Protection of Military Remains Act. It is illegal to interfere with the wreck of a crashed military aircraft unless licensed to investigate by the Ministry of Defence.

As with ship wrecks, the location of many crash sites remains unknown and vulnerable to activities such as dredging. In recent years Wessex Archaeology have been commissioned by English Heritage through the Aggregates Levy Sustainability fund to review aircraft crash sites in our coastal waters and provide guidance for dredging companies.

Statement of Significance

Dover District has a wealth of wreck sites both offshore and potentially inland in areas reclaimed from the sea. These wrecks are an immensely valuable resource testifying to the prolonged importance of the region for maritime trade, transport and defence and the long history of navigation through and across the Strait of Dover. Collectively, and due to the number of very important individual examples, the wrecks are of outstanding significance.

Evidential Value

The wreck sites have considerably high value in potentially providing important evidence on a number of nationally important issues. The vessels themselves demonstrate the history and nature of navigation through and across the Dover Strait and along the coastal waters and channels from prehistoric times. The evidence of their cargoes in particular can provide important new information on the trade contacts and the movements of goods and in some cases peoples to and from the continent, around Europe and further afield. Many of the wrecks have particular value in representing exemplars of vessel types, cargos and particular maritime activities, namely transport, trade and warfare and demonstrate the development of craft and boat building skills through the ages. They also provide considerable potential to help us understand the lives of the mariners. For example, the well-preserved wrecks of the Stirling Castle, Northumberland and Restoration provide an important resource to better understand the navy of the beginning of the eighteenth century. Many wrecked vessels and crashed aircraft can be associated with documented events such as the great naval conflicts and the Battle of Britain. They have considerable potential to provide direct evidence of these conflicts.

Historical Illustrative Value

The wreck sites have the potential to illustrate the development of maritime craft from early times through to the twentieth century. They can help to illustrate the development of navies and naval warfare and the lives of naval seamen. Through the cargoes the historical development of trading contact between Britain and Europe and later between the European powers and their developing overseas empires.

Historical Associative Value

Many of the wrecks can be associated with nationally significant events. There is considerable potential to provide direct evidence for both the expeditions by Cæsar in 55 and 54 BC and the later Roman invasion of AD 43. Wrecks or hulks associated with these events would help to confirm the location of the three landings. There is potential for the remains of wrecks associated with the various documented conflicts that have taken place in the waters around the Dover coastline including those between the Saxons and Danes, the two Battles of Sandwich and the Battle of the Downs between the Spanish and Dutch fleets. There is even greater potential for wrecks associated with natural events such as the Great Storm of 1703 which wrecked a large number of vessels in the Downs. The remains of vessels associated with the First and Second World War and aircraft lost in the Battle of Britain can help to illustrate these nationally significant events.

Aesthetic Value

The presence of wrecks protruding from the Goodwin Sands are evocative reminders of the maritime past and the hazards that the coastal waters held for the shipping and mariners. Many of the great naval conflicts have been captured in evocative and dramatic works of art and in literature. Many of the accounts of the wrecking are evocative in their telling.

Communal Value

The connection of the District's coastal communities with their maritime heritage is strong. The shipwrecks themselves provide reminders of the past and for Deal in particular a strong connection between the town and the wrecks on the Goodwins. The role that Deal Boatmen and the lifeboats at Deal and Walmer played in saving numerous lives at sea is a point of local pride. The Walmer Lifeboat still rescues mariners from these waters.

The naval life, particularly at the time of the French and Napoleonic Wars generates a significant level of public interest particularly through popular fiction by Forester, O'Brian and others. The discovery of shipwrecks fires the public's imagination and helps to illustrate the events and times associated with them. As artefacts recovered from the seabed are often well preserved the wrecks can provide discoveries that immediately connect with the public. The wrecks of the twentieth century and the aircraft crash sites of the Battle of Britain serve as memorials to these conflicts and are losses that still live in the memories of the coastal communities of the District.

The history of the wrecks and objects salvaged from them have considerable interpretative potential. The closure of the Maritime Museum at Ramsgate and the temporary closure of the Deal Maritime Museum have reduced the interpretation of the District's Maritime Heritage. The Bronze Age Boat Gallery at Dover Museum is an important heritage visitor attraction and demonstrates the tourism and educational potential of the boat.

Vulnerabilities

The most significant threat to the long term future of the historic wrecks and crashed aircraft at sea is from the dynamic environment in which they rest. The sand banks of the Goodwin Sands are highly mobile and wrecks appear and are re-buried quite regularly. Monitoring of wrecks such as the Stirling Castle have illustrated how a well preserved wreck can quickly deteriorate once it is exposed to the marine processes with the wreck structures suffering collapse and objects being washed away. The condition and exposure of the more important wreck sites in the District's coastal waters should be regularly monitored through inspection and geophysical survey with systematic recording and recovery of objects when necessary.

English Heritage have reviewed the condition of the country's Protected Wreck Sites and included seven on its Heritage at Risk Register for 2011. Four of these wrecks lie on the Goodwin Sands – the Northumberland, Restoration, Stirling Castle and the Rooswijk. All wrecks were recognised as suffering from the mobile nature of the Goodwin sediments:

"Sands change morphology on a seasonal basis leading to periodic exposure of the vessel's wooden hulls. Exposed timbers are weakened by biological attack and may be subject to detachment and dispersal by tide and wave surge during winter storms." (Northumberland and Restoration).

"As with other sites in the Goodwins, archaeological material is at risk owing to mobile sediments causing periodic exposure." (Rooswijk)

The wrecks and aircraft crash sites also remain vulnerable to interference and disturbance by divers. All but seven of the District's wreck sites are not protected by designation and divers are able to legally dive on the wrecks without licence. Most act responsibly, respect and do not disturb the wrecks and report findings to the Receiver of Wreck. Under the Marine and Coastal Areas Act anyone who wishes to remove an object from a wreck, or from the seafloor, with the aid of a platform, vessel or other surface support system must first have a marine licence, which are granted by the Marine Management Organisation. Many divers belong to clubs with codes of responsible diving and the British Sub Aqua Club have an Underwater Heritage Advisor and support initiatives to protect the country’s wreck heritage. There are a minority however who undertake unauthorised access on wrecks, disturb and remove artefacts irresponsibly and without reporting either for souvenirs or for potential financial gain.

Dredging operations at sea and the exploitation of the sand and shingle of the sea floor can have a significant impact on wrecks and crash sites. While the location of known wrecks can be highlighted to operators, many sites are not located and are at considerable risk. While new areas of sea bed operations are normally assessed prior to granting of a licence, there remains a high potential for new wrecks to be discovered and disturbed. Recognising this the British Marine Aggregate Producers Association, English Heritage and the Crown Estates have in place a protocol for reporting finds and a guidance note for archaeological good practice developed by Wessex Archaeology to assist in protection of the submerged heritage. The following links will take the reader to the finds reporting protocol and the guidance note:

- http://www.wessexarch.co.uk/projects/marine/bmapa/index.html

- http://www.wessexarch.co.uk/projects/marine/bmapa/dredging-hist-env.html

Other forms of sea bed development, such as the construction of off shore wind farms, the laying of sea bed cables and pipelines can also have an impact on submerged wrecks and crashed aircraft. English Heritage works to ensure any marine development within the English area of the UK's territorial waters includes a full consideration of the potential for impacts on maritime heritage assets in the project planning stage. In this way such impacts are appropriately mitigated prior to the commencement of any works and in addition there is also now a protocol for reporting finds during offshore windfarm development projects. Disturbance can arise not only from development works, but also from the anchoring of vessels on wreck sites. Fishing with nets is a further potential source of damage to wrecks, though normally most fishing vessels have good knowledge of the location of submerged obstructions.

Wrecks and hulks buried within the alluvial sediments of the District's reclaimed lands could potentially be well preserved as the waterlogged and anaerobic conditions help to preserve organic remains including timber. The change in hydrology of the sediments around these preserved remains could lead to accelerated loss of the organic remains. The remaining part of the Dover Bronze Age Boat left beneath properties in Dover may be particularly vulnerable as the construction of the adjacent underpass is likely to have altered the environmental conditions of the area. As with any buried archaeology the buried hulks and wrecks are vulnerable to development works where they coincide though this would generally be through deep groundwork such as piling.

Opportunities

There is little that can be done to prevent the exposure of wreck sites to the elements but through a programme of regular monitoring through diver observation and remote survey can help management decisions to be undertaken. English Heritage is encouraging a programme of voluntary licensees to help monitor the Protected Wreck sites around our coast both in terms of their condition and access.

Support for programmes of survey that identify the locations and significance of key wreck and crash sites will assist in considerations of where additional protection through designation is required and where further monitoring should be in place. Information on the location of known wreck sites and clear guidance on their safeguarding should be made available in an accessible form, to stakeholders, particularly those who have operational interests off shore and with the sea bed such as divers, dredging operators and fishermen.

At present the position of finds from wrecks very much remains to emphasise a 'look but don't touch approach'. Any finds must first be reported to the Receiver of Wrecks who plays the main part in identifying them and then determining their ownership. Nevertheless the process would benefit from improved procedures for findings that are reported to the Receiver of Wrecks to be updated on to the Kent Historic Environment Record.

The discovery of wrecks and aircraft often catches the public attention and imagination. Opportunities should be taken to promote the District's maritime heritage in conjunction with such discoveries and to take advantage and celebrate key events such as the forthcoming lifting of Dornier 17, the possible reconstruction of the Dover Bronze Age Boat or key anniversaries of some of the significant events in the District’s maritime history.

The Deal Maritime Museum is an important interpretation asset for the theme and even more so since the closure of the Maritime Museum at Ramsgate. The Museum should be encouraged to play a lead role in celebration and interpretation of the maritime history of the District. There is a role for interpretation panels at public locations on the promenades at Deal and Dover that explain the wrecks and the maritime history of the area.

A DMS value is converted to decimal degrees using the formula (D + M/60 + S/3600).

Click here or here to convert DMS coordinates to DD (and vice versa).

| Name | Type | Date | Weight | Latitude N (DM) | Longitude E (DM) | Depth (m) | Proud (m) | Latitude N (DMS) | Longitude E (DMS) |

| Unknown | WWII Cargo Ship | 31 | 7 | 51° 03' 45" | 01° 22' 03" | ||||

| Unknown | 30 | 6 | 51° 04' 20" | 01° 22' 54" | |||||

| SS Maloja | Ocean Liner | 1916 | 12431 | 51.04.270 | 1.18.520 | 21 | 5 | 51° 04' 51" | 01° 18' 18" |

| W.A.Scholten | Dutch Liner | 1887 | 2589 | 33 | 12 | 51° 04' 54" | 01° 24' 40" | ||

| Amplegarth | Collier | 1918 | 3707 | 51.05.379 | 1.20.252 | 32 | 11 | 51° 05' 20" | 01° 20' 21" |

| Unknown | Steamer | 30 | 5 | 51° 05' 27" | 01° 16' 31" | ||||

| SS Amulree | Yacht (Steamer) | 1940 | 86 | 51.05.477 | 1.21.437 | ||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 30 | 10 | 51° 05' 35" | 01° 21' 21" | ||||

| Helene | 26 | 51° 05' 36" | 01° 16' 17" | ||||||

| HMT Peridot | Armed Trawler | 1940 | 398 | 51.05.600 | 1.25.733 | 30 | 10 | 51° 05' 36" | 01° 25' 44" |

| Empire Lough | Steamer | 1944 | 2824 | 8 | 1 - 2 | 51° 05' 38" | 01° 14' 40" | ||

| Halcyon | Steamer | 1916 | 1319 | 21 | 7 | 51° 05' 38" | 01° 16' 01" | ||

| Unknown (small) | 20 | 51° 05' 41" | 01° 16' 15" | ||||||

| Traquair | Collier | 1916 | 1067 | 26 | 8 | 51° 05' 42" | 01° 18' 53" | ||

| Efford (part) | Cargo Steamer | 1940 | 339 | 25 | 5 | 51° 05' 42" | 01° 20' 14" | ||

| Unknown | Steamer | 23 | 4 | 51° 05' 48" | 01° 19' 37" | ||||

| HMS Torbay II | Steam Drifter | 1940 | 25 | 4 | 51° 05' 49" | 01° 17' 52" | |||

| SS Strathclyde | Cargo Steamer | 1876 | 1951 | 51.05.633 | 1.21.225 | 22 – 30 | |||

| MTB | Motor Torpedo Boat | 51.05.917 | 1.21.300 | ||||||

| Unknown | Cargo Steamer | 22 | 4 | 51° 05' 54" | 01° 18' 52" | ||||

| Efford (part) | Cargo Steamer | 1940 | 339 | 24 | 6 | 51° 05' 54" | 01° 19' 43" | ||

| MTB | Motor Torpedo Boat | 25 | 4 | 51° 05' 55" | 01° 21' 18" | ||||

| The Groove | Seabed Fissure | 51.05.933 | 1.20.867 | 21 | 51° 05' 56" | 01° 20' 52" | |||

| Unknown | 21 | 51° 05' 58" | 01° 19' 38" | ||||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 29 | 10 | 51° 06' 07" | 01° 22' 06" | ||||

| Unknown | 15 | 1 | 51° 06' 18" | 01° 20' 09" | |||||

| U-11 | Submarine | 1914 | 46 | 9 | 51° 06' 20" | 01° 29' 45" | |||

| Unknown | 14 | 2 | 51° 06' 22" | 01° 20' 18" | |||||

| Unknown | 17 | 1 | 51° 06' 27" | 01° 19' 00" | |||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 19 | 4 | 51° 06' 27" | 01° 21' 04" | ||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 21 | 5 | 51° 06' 28" | 01° 21' 30" | ||||

| Unknown | 12 | 1 | 51° 06' 33" | 01° 19' 14" | |||||

| Lady Stella | Motor Vessel | 1958 | 5160 | 51.06.566 | 1.20.900 | 18 | 2 | 51° 06' 34" | 01° 20' 54" |

| Ouzel | 51.06.117 | 1.22.100 | |||||||

| Unknown | 12 | 2 | 51° 06' 34" | 01° 19' 03" | |||||

| Unknown | 13 | 51° 06' 35" | 01° 20' 19" | ||||||

| HMS War Sepoy | WW1 Standard Tanker | 1940 | 5800 | 51.06.836 | 1.19.753 | 51° 06' 42" | 01° 19' 45" | ||

| Unknown | 21 | 6 | 51° 06' 42" | 01° 21' 30" | |||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 20 | 5 | 51° 06' 44" | 01° 21' 42" | ||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 27 | 4 | 51° 06' 45" | 01° 22' 57" | ||||

| Unknown | 24 | 3 | 51° 06' 45" | 01° 22' 34" | |||||

| Unknown | 26 | 6 | 51° 06' 46" | 01° 23' 57" | |||||

| Spanish Prince | WW1 Blockship | 51.06.776 | 1.19.736 | 11 | 1.1 | 51° 06' 47" | 01° 19' 51" | ||

| Unknown | 26 | 3 | 51° 06' 48" | 01° 24' 27" | |||||

| MTB 218 | Motor Torpedo Boat | 1942 | 35 | 39 | 7 | 51° 06' 52" | 01° 37' 10" | ||

| Unknown 1 | 51.06.300 | 1.20.150 | |||||||

| Unknown 2 | 51.06.367 | 1.20.300 | |||||||

| Unknown 3 | 51.06.450 | 1.21.067 | |||||||

| Lisbeth M | 51.06.511 | 1.20.946 | |||||||

| Unknown 4 | 51.06.583 | 1.20.317 | |||||||

| Unknown 5 | 51.06.700 | 1.21.500 | |||||||

| Unknown 6 | 51.06.733 | 1.21.700 | |||||||

| Unknown 7 | 51.06.750 | 1.22.567 | |||||||

| HMS Rondino | Admiralty Trawler | 1940 | 230 | 51.07.000 | 1.23.917 | 27 | 5 | 51° 07' 00" | 01° 23' 55" |

| Unknown | 15 | 1 | 51° 07' 01" | 01° 20' 59" | |||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 25 | 3 | 51° 07' 03" | 01° 25' 53" | ||||

| Unknown | 44 | 51° 07' 07" | 01° 35' 28" | ||||||

| Fancy | British Gaff Cutter | 1974 | 51° 07' 12" | 01° 21' 12" | |||||

| Unknown | 13 | 1 | 51° 07' 13" | 01° 21' 12" | |||||

| UC-46 | Submarine | 1917 | 51.06.849 | 1.37.019 | 35 | 51° 07' 13" | 01° 30' 07" | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 51° 07' 15" | 01° 21' 12" | ||||||

| Unknown | Barge | 1989 | 11 | 3 | 51° 07' 18" | 01° 20' 44" | |||

| HMS Kingston Galena | Admiralty Trawler | 1940 | 550 | 51.07.333 | 1.24.789 | 25 | 5 | 51° 07' 18" | 01° 24' 52" |

| Maine | 51.07.549 | 1.30.218 | |||||||

| Comfort | 51.07.550 | 1.27.010 | |||||||

| Unknown | Bronze Age Arms Trader | 1100 BC | 51° 07' 36" | 01° 20' 48" | |||||

| HMS Bonar Law | Admiralty Trawler | 1915 | 284 | 51.07.699 | 1.24.569 | 27 | 5 | 51° 07' 38" | 01° 24' 39" |

| Sigrid | Dutch 3-Masted Schooner | 100 | 5 | 51° 07' 40" | 01° 21' 02" | ||||

| Summity | Motor Vessel | 1940 | 554 | 51° 07' 42" | 01° 20' 52" | ||||

| SS Toward | Merchant Steamer | 1915 | 1218 | 51.07.758 | 1.25.015 | 25 | 8 | 51° 07' 44" | 01° 25' 02" |

| Falcon | Steamer | 1926 | 675 | 51° 07' 52" | 01° 21' 07" | ||||

| Emma (Dover) | Swedish Steamer | 1940 | 990 | 51.07.966 | 1.23.695 | 25 | 7 | 51° 07' 56" | 01° 23' 47" |

| SS Eidsiva | Norwegian Cargo Steamer | 1915 | 1092 | 51.08.061 | 1.25.149 | 27 | 10 | 51° 07' 59" | 01° 25' 15" |

| Preussen | Steel Sailing Ship | 1910 | 5081 | 51° 08' 01" | 01° 22' 10" | ||||

| Notre Dame de Lourdes | Fishing Vessel | 1917 | 47 | 51° 08' 01" | 01° 22' 10" | ||||

| SS The Queen | Merchant Steamer | 1916 | 1676 | 51.08.067 | 1.27.405 | 27 | 8 | 51° 08' 03" | 01° 27' 24" |

| HMS Othello II | Admiralty Trawler | 1915 | 206 | 51.08.101 | 1.24.616 | 27 – 29 | 5 | 51° 08' 04" | 01° 24' 40" |

| Unknown 8 | 51.08.129 | 1.31.946 | |||||||

| Unknown 9 | 51.08.133 | 1.32.000 | |||||||

| White Rose | Wooden Sailing Vessel | 25 | 3 | 51° 08' 05" | 01° 23' 38" | ||||

| HMS Aries | Admiralty Yacht | 1915 | 268 | 51° 08' 07" | 01° 23' 48" | ||||

| Unknown | 46 | 51° 08' 08" | 01° 32' 00" | ||||||

| SS Hundvaag | Cargo Steamer | 1940 | 690 | 28 | 6 | 51° 08' 08" | 01° 26' 46" | ||

| Saint Ronan | Trawler | 1959 | 568 | 51.08.167 | 1.32.667 | 36 – 50 | 51° 08' 10" | 01° 32' 40" | |

| Francesco Ciampa | Italian Steamer | 1927 | 3611 | 51.08.216 | 1.29.733 | 27 | 9 | 51° 08' 13" | 01° 29' 44" |

| G-42 | German MTB Destroyer | 1917 | 1147 | 48 | 10 | 51° 08' 17" | 01° 34' 57" | ||

| SS Carmen | Panamanian Steamer | 1963 | 4240 | 51.08.312 | 1.36.319 | 43 | 17 | 51° 08' 17" | 01° 36' 26" |

| Andaman | Swedish Motorship | 1953 | 4765 | 49 | 24 | 51° 08' 21" | 01° 33' 57" | ||

| HMS The Boys | Admiralty Drifter | 1940 | 92 | 51.08.337 | 1.31.380 | 46 | 51° 08' 30" | 01° 32' 12" | |

| Submarine (East) | Submarine | 51.08.383 | 1.28.333 | 20 | 51° 08' 23" | 01° 28' 20" | |||

| HMS Weigelia | Admiralty Trawler | 1916 | 262 | 51.08.530 | 1.27.109 | 25 | 5 | 51° 08' 32" | 01° 27' 13" |

| SGO Lightvessel 69 | Lightvessel | 1940 | 51.08.642 | 1.28.151 | 25 | 3 | 51° 08' 36" | 01° 28' 13" | |

| (freshwater spring) | 27 | 3 | 51° 08' 37" | 01° 29' 47" | |||||

| Unknown 12 | 51.08.902 | 1.24.107 | |||||||

| Unknown 10 | 51.08.946 | 1.24.117 | |||||||

| SS Hundvaag | Cargo Steamer | 1940 | 686 | 51.06.133 | 1.26.767 | 25 | 8 | 51° 08' 41" | 01° 27' 55" |

| HMS Cayton Wyke | Anti-Submarine Trawler | 1940 | 373 | 23 | 5 | 51° 08' 58" | 01° 28' 17" | ||

| Unknown | Steamer | 34 | 6 | 51° 08' 52" | 01° 32' 28" | ||||

| Sambut | Liberty Ship | 1944 | 7176 | 51 | 19 | 51° 08' 52" | 01° 33' 27" | ||

| Eleonora | German Motor Vessel | 1979 | 499 | 51.08.995 | 1.30.119 | 26 | 7 | 51° 08' 55" | 01° 30' 08" |

| SS Loanda | Steamer | 1908 | 2702 | 51.08.982 | 1.24.583 | 20 | 7 | 51° 08' 57" | 01° 24' 43" |

| Etoile Polaire | Trawler | 51.08.986 | 1.28.197 | ||||||

| SS Friesland | Cargo (Steamer) | 1940 | 681 | 51.09.0 | 1.28.0 | ||||

| UAT | 51.09.121 | 1.25.727 | |||||||

| U-16 | Submarine | 1939 | 329 | 51.09.133 | 1.28.126 | 25 | 6 | 51° 09' 05" | 01° 28' 12" |

| HMS Unknown | Armed Trawler | 21 | 6 | 51° 09' 06" | 01° 25' 41" | ||||

| Unknown | 27 | 1 | 51° 09' 15" | 01° 30' 31" | |||||

| Unknown | Coney Burrow Point | 2 | 1 | 51° 09' 16" | 01° 23' 59" | ||||

| Unknown | 27 | 4 | 51° 09' 18" | 01° 32' 36" | |||||

| Olympia | Sailing Ketch | 1918 | 51.09.400 | 1.24.533 | 16 | 1 | 51° 09' 24" | 01° 24' 32" | |

| HMS B-2 | Submarine | 1912 | 287 | 51.09.427 | 1.24.421 | ||||

| HMT Saxon Prince | Armed Trawler | 1916 | 237 | 51.09.600 | 1.25.753 | 15 – 23 | 51° 09' 33" | 01° 25' 48" | |

| Unknown | Steamer | 28 | 5 | 51° 09' 37" | 01° 32' 38" | ||||

| Nancy Moran | American Tug | 452 | 51.09.617 | 1.27.733 | 24 | 51° 09' 37" | 01° 27' 44" | ||

| HMS Lydian | Armed Trawler | 1915 | 244 | 51.09.711 | 1.26.083 | 24 | 7 | 51° 09' 39" | 01° 26' 14" |

| Hosanna | Beam Trawler | 1980 | 97 | 51.10.102 | 1.34.112 | 47 | 51° 09' 45" | 01° 34' 24" | |

| Bucket Dredger (Deal) | Dredger | 51.09.617 | 1.26.500 | 23 | 6 | 51° 09' 49" | 01° 26' 30" | ||

| L'Armandeche | Wooden French Fishing Trawler | 1982 | 51° 09' 53" | 01° 30' 37" | |||||

| Unknown | Fishing Vessel | 23 | 51° 09' 54" | 01° 31' 00" | |||||

| Unknown 11 | 51.10.853 | 1.35.575 | |||||||

| Santagata | Italian Motor Vessel | 1950 | 7011 | 5 – 18 | 51° 10' 27" | 01° 31' 24" | |||

| Agen | French Steamer | 1952 | 4186 | 26 | 12 | 51° 10' 42" | 01° 31' 44" | ||

| Unknown | Fishing Boat | 44 | 51° 10' 50" | 01° 35' 40" | |||||

| Le Pelerin de la Mer | 45 | 51° 10' 52" | 01° 34' 00" | ||||||

| Golden Sunset | Fishing Vessel | 1977 | 300 yds off Kingsdown Beach | 51° 10' 58" | 01° 24' 30" | ||||

| Unknown | 7 | 51° 10' 59" | 01° 31' 50" | ||||||

| Luray Victory | American Steamer | 1946 | 7612 | 1 | 51° 11' 03" | 01° 31' 38" | |||

| Unknown | Steamer | 41 | 7 | 51° 11' 07" | 01° 38' 10" | ||||

| Unknown | 26 | 6 | 51° 11' 07" | 01° 33' 00" | |||||

| The Hulk | 21 | 5 | 51° 11' 10" | 01° 27' 18" | |||||

| Peter Hawksfield | Paddle Steamer | 16 | 5 | 51° 11' 11" | 01° 25' 54" | ||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 51 | 6 | 51° 11' 28" | 01° 36' 41" | ||||

| PSS Dolphin | Paddle Steamer | 1885 | 641 | 51.11.490 | 1.25.260 | 7.6 | 3 | 51° 11' 49" | 01° 25' 26" |

| Admiral Gardner | East Indiaman | 1809 | 813 | 51.12.010 | 1.30.454 | 51° 12' 00" | 01° 30' 56" | ||

| Unknown | Sailing Ship | 51° 12' 02" | 01° 24' 27" | ||||||

| The Adjutant | Steamer | 10 | 51° 12' 12" | 01° 26' 15" | |||||

| Unknown | 18.1 | 1 | 51° 12' 12" | 01° 28' 15" | |||||

| North Eastern Victory | Victory type Liberty Ship | 1946 | 7176 | 3 | 51° 12' 22" | 01° 31' 24" | |||

| Unknown | 48 | 8 | 51° 12' 36" | 01° 35' 54" | |||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 16 | 3 | 51° 12' 44" | 01° 31' 14" | ||||

| Flandres | Belgian Steamer | 1940 | 5827 | 15 | 2 | 51° 12' 51" | 01° 27' 21" | ||

| Silvio Onarato | Italian Steamer | 1948 | 2327 | 51° 12' 53" | 01° 33' 04" | ||||

| James Harrod | Liberty Ship | 1945 | 7176 | 51° 12' 59" | 01° 24' 38" | ||||

| Longhirst | Steamer | 1901 | 2048 | 49 | 51° 13' 00" | 01° 36' 00" | |||

| SS Patria | Ocean Liner (Steamer) | 1899 | 7188 | 51.13.01 | 1.26.03 | 10.5 | 2 | 51° 13' 01" | 01° 26' 03" |

| HMS Tranquil | Requisitioned Trawler | 1942 | 294 | 17 | 5 | 51° 13' 08" | 01° 27' 51" | ||

| Britannia | Wooden Ship (East Indiaman ?) | 51° 13' 08" | 01° 32' 02" | ||||||

| HMS Carlisle | Ship of the Line (4th Rate) | 1700 | 709 | 51.13.071 | 1.26.476 | ||||

| Jacob Luckenbach | American Steamer | 1916 | 2793 | 14 | 2 | 51° 13' 10" | 01° 26' 33" | ||

| HMS Niger | MTB | 1914 | 810 | 51.13.120 | 1.26.290 | 14 | 3 | 51° 13' 12" | 01° 26' 29" |

| Brick Barge | 12 | 1.5 | 51° 13' 15" | 01° 25' 48" | |||||

| HMS Greyhound | Frigate - 6th Rate | 1781 | 617 | 51.13.334 | 1.27.562 | ||||

| Dinard | French Steamer | 1939 | 522 | 6 | 2 | 51° 13' 34" | 01° 25' 04" | ||

| Africa | British Steamer | 1915 | 1038 | 4 | 51° 13' 50" | 01° 24' 43" | |||

| Nora | Dutch Motor Vessel | 1940 | 298 | 51° 13' 50" | 01° 25' 10" | ||||

| Unknown | 52 | 12 | 51° 14' 00" | 01° 36' 48" | |||||

| Marauder | Bomber | Kellett Gut | 19 | 51° 14' 02" | 01° 31' 29" | ||||

| HMS Aragonite (stern) | Armed Trawler | 1939 | 315 | 4 | 51° 14' 08" | 01° 24' 59" | |||

| British Navy | Sailing Ship | 1881 | 1216 | 11 | 4 | 51° 14' 08" | 01° 26' 31" | ||

| HMS Aragonite (bow & midsection) | Armed Trawler | 1939 | 315 | 3 | 51° 14' 14" | 01° 25' 00" | |||

| Ashley | British Collier | 1940 | 1323 | 51° 14' 25" | 01° 34' 29" | ||||

| Mahratta | 1909 | 5730 | 15 | 1 | 51° 14' 27" | 01° 28' 52" | |||

| Unknown | 11 | 1 | 51° 14' 38" | 01° 27' 14" | |||||

| HMS Napia | British Tug | 1939 | 155 | 6 | 1 | 51° 14' 41" | 01° 25' 11" | ||

| HMS Marcella | Yacht | 1916 | 127 | 51.14.44 | 1.26.08 | 10 | 5 | 51° 14' 44" | 01° 26' 08" |

| Mahratta II | 1939 | 6690 | 17 | 11 | 51° 14' 45" | 01° 30' 05" | |||

| Unknown | 2 | 51° 14' 46" | 01° 34' 15" | ||||||

| Rynanna | Steamer | 1940 | 3 | 51° 14' 52" | 01° 34' 22" | ||||

| Llaro | British Merchantman | 1915 | 2799 | 5 | 3 | 51° 14' 53" | 01° 24' 39" | ||

| Montrose | Liner (Blockship) | 1914 | 7207 | 1 | 51° 14' 56" | 01° 34' 12" | |||

| SS Belgier II | Cargo (Steamer) | 1939 | 5182 | 51.14.550 | 1.29.120 | ||||

| Kabinda | Belgian Steamer | 1939 | 5030 | 12 | 3 | 51° 15' 03" | 01° 29' 17" | ||

| Unknown | 1945 | 6 | 1 | 51° 15' 06" | 01° 25' 11" | ||||

| Unknown | 21 | 51° 15' 10" | 01° 34' 03" | ||||||

| Piave | American Steamer | 1919 | 6000 | 16 | 2 | 51° 15' 17" | 01° 30' 20" | ||

| Lancresse | Steamer | 1935 | 4 | 51° 15' 21" | 01° 27' 48" | ||||

| Unknown | 10 | 51° 15' 28" | 01° 34' 35" | ||||||

| Unknown (x2) | 9 | 1 | 51° 15' 33" | 01° 34' 43" | |||||

| HMS Northumberland | Ship of the line - 3rd Rate | 1703 | 1041 | 51.15.27 | 1.30.07 | 51° 15' 45" | 01° 30' 12" | ||

| East Goodwins Lightvessel | Lightvessel | 1940 | 46 | 6 | 51° 15' 49" | 01° 36' 46" | |||

| HMS Restoration | Ship of the line - 3rd Rate | 1703 | 1018 | 51.15.360 | 1.30.078 | 51° 15' 60" | 01° 30' 12" | ||

| Unknown | Steamer | 14 | 51° 16' 00". | 01° 34' 59" | |||||

| HMS Stirling Castle | Ship of the line - 3rd Rate | 1703 | 1059 | 51.16.426 | 1.30.516 | ||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 4 | 51° 16' 17". | 01° 29' 30" | |||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 16 | 5 | 51° 16' 23". | 01° 34' 27" | ||||

| La Nantaise | British Steamer | 1945 | 359 | 10 | 51° 16' 30". | 01° 29' 02" | |||

| Koenigshaven | Norwegian Steamer | 1917 | 1245 | 13 | 3 | 51° 16' 38". | 01° 28' 03" | ||

| Malta | 1917 | 1245 | 13 | 5 | 51° 16' 39". | 01° 28' 13" | |||

| Lord Hamilton | Barge | 1924 | 64 | 19 | 2 | 51° 16' 52". | 01° 34' 19" | ||

| Unknown | Steamer | 14 | 51° 17' 03" | 01° 29' 23" | |||||

| Egero | Norwegian Steamer | 1916 | 1373 | 14 | 2 | 51° 17' 06" | 01° 29' 04" | ||

| Egero | Norwegian Steamer | 1916 | 1373 | 14 | 2 | 51° 17' 06" | 01° 29' 04" | ||

| U-48 | Submarine | 1917 | 940 | 51.17.00 | 1.31.00 | 51° 17' 06" | 01° 29' 48" | ||

| SS Mersey | Merchant Steamer | 1940 | 1037 | 51.17.00 | 1.28.00 | 12 | 2 | 51° 17' 10" | 01° 28' 09" |

| Unknown | Steamer | 12 | 4 | 51° 17' 24" | 01° 29' 45" | ||||

| Lancaster Bomber | Pegwell Bay | 2 | 51° 17' 40" | 01° 23' 12" | |||||

| Unknown | 20 | 3 | 51° 17' 40" | 01° 35' 50" | |||||

| Brendonia | Collier | 1939 | 313 | 11 | 2 | 51° 17' 54" | 01° 29' 44" | ||

| Unknown | 11 | 1 | 51° 17' 59" | 01° 28' 07" | |||||

| Brighton Belle | Paddle Steamer | 1940 | 396 | 11 | 2 | 51° 18' 00" | 01° 30' 25" | ||

| Bravore | Norwegian Collier | 1940 | 1458 | 51.18.380 | 1.30.540 | 12 | 1 | 51° 18' 30" | 01° 30' 51" |

| HMS Harvest Moon | Trawler | 1940 | 72 | Richborough Channel Blockship | 51° 18' 45" | 01° 22' 07" | |||

| HMS Alfred Colebrook | Drifter | 1940 | 56 | Richborough Channel Blockship | 51° 18' 47" | 01° 22' 08" | |||

| Unknown | 15 | 0.5 | 51° 18' 51" | 01° 33' 38" | |||||

| Unknown | 18 | 5 | 51° 18' 59" | 01° 36' 38" | |||||

| Rydal Force | British Collier | 1940 | 1101 | 9 | 51° 19' 02" | 01° 30' 59" | |||

| Neg Chieftain | Panamanian Tug | 1983 | 3 | 51° 19' 14" | 01° 27' 42" | ||||

| Harcalo | British Steamer | 1940 | 5081 | 7 | 3 | 51° 19' 36" | 01° 30' 12" | ||

| Merel | British Steamer | 1939 | 1088 | 11 | 51° 19' 37" | 01° 30' 49" | |||

| HMS Arctic Trapper | Admiralty Trawler | 1941 | 352 | 11 | 1 | 51° 19' 37" | 01° 31' 07" | ||

| Unknown | Dutch Schooner | 1940 | 24 | 7 | 51° 19' 37" | 01° 37' 40" | |||

| HMS Elizabeth Angela | Admiralty Trawler | 1940 | 253 | 14 | 3 | 51° 19' 51" | 01° 33' 05" | ||

| Correct | Steamer | 1916 | 13 | 2 | 51° 19' 51" | 01° 33' 14" | |||

| Liberator | B-24 Bomber | 19 | 4 | 51° 20' 04" | 01° 30' 05" | ||||

| UB-12 | Submarine | 1918 | 142 | 51° 20' 04" | 01° 30' 05" | ||||

| Greypoint | Steamer | 1917 | 894 | 10 | 51° 20' 20" | 01° 29' 30" | |||

| Unknown | 7 | 2 | 51° 20' 24" | 01° 28' 17" | |||||

| Alert | British Cableship | 1945 | 941 | 18 | 2 | 51° 20' 44" | 01° 37' 40" | ||

| Klar | Norwegian Collier | 1915 | 518 | 12 | 51° 21' 03" | 01° 32' 49" | |||

| Yvonne | Belgian Steamer | 1940 | 668 | 51° 21' 06" | 01° 32' 48" | ||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 19 | 7 | 51° 21' 25" | 01° 37' 51" | ||||

| Unknown | 20 | 4 | 51° 21' 37" | 01° 37' 54" | |||||

| Unknown | Steamer | 22 | 3 | 51° 21' 38" | 01° 37' 17" | ||||

| Unknown | 12 | 51° 21' 54" | 01° 33' 30" | ||||||

| Cathy | Danish Steamer | 1915 | 4076 | 14 | 3 | 51° 22' 00" | 01° 34' 25" | ||

| HMS Frons Oliviae | Admiralty Trawler | 1915 | 98 | 12 | 2 | 51° 22' 02" | 01° 32' 34" | ||

| SS Lolworth | Merchant Steamer | 1940 | 1969 | 51.22.00 | 1.26.00 | 9 | 1 | 51° 22' 07" | 01° 30' 59" |

| Obstruction | 3 | 1 | 51° 22' 36" | 01° 27' 20" | |||||

| Dunbar Castle | 1940 | 10002 | 18 | 3 | 51° 22' 38" | 01° 36' 18" | |||

| Rock Pinnacle (?) | 11 | 3 | 51° 22' 50" | 01° 30' 49" | |||||

| Wreckage | 11 | 1 | 51° 22' 58" | 01° 30' 44" | |||||

| Cedrington Court | British Standard Ship | 1940 | 5160 | 16 | 2 | 51° 23' 02" | 01° 35' 49" | ||

| Selma | Norwegian Steamer | 1915 | 1654 | 17 | 51° 23' 02" | 01° 34' 25" | |||

| HMS Carilon | Admiralty Trawler | 1915 | 226 | 13 | 3 | 51° 23' 26" | 01° 31' 18" | ||

| Surrey | British Dredger | 1960 | 12 | 3 | 51° 23' 30" | 01° 32' 31" | |||

| Unknown | 14 | 3 | 51° 23' 38" | 01° 31' 06" | |||||

| HMS Tourmaline | Trawler | 1941 | 641 | 15 | 51° 23' 44" | 01° 31' 14" | |||

| HMS Fauvette | Armed Boarding Steamer | 1916 | 2644 | 17 | 4 | 51° 24' 01" | 01° 29' 00" | ||

| Unknown | 17 | 4 | 51° 24' 02" | 01° 36' 19" | |||||

| Opal | Barge | 1921 | 9 | 51° 24' 03" | 01° 22' 03" | ||||

| Unknown | 8 | 51° 24' 16" | 01° 23' 23" | ||||||

| Emile Deschamps | French Auxiliary Minesweeper | 1940 | 349 | 51.24.18 | 1.29.18 | 12 | 2 | 51° 24' 21" | 01° 29' 21" |

| HMS Tartarus | Sailing Ship | 1804 | 344 | 51.26.429 | 1.19.713 | ||||

| Karmt MV | Tanker | 1945 | 4991 | 51.27.0 | 1.43.0 | ||||

| Rooswijk | Dutch East Indiaman | 1740 | 850 | 51.27405 | 1.575617 | 18 | <1 | ||

| SS Newlands | Cargo (Steamer) | 1945 | 1556 | 51.28.00 | 1.28.00 | ||||

| SS Menapier | Cargo (Steamer) | 1915 | 1886 | 51.28.050 | 1.35.150 | ||||

| SS Girasol | Merchant Ship (Steamer) | 1940 | 648 | 51.28.50 | 1.22.15 | ||||

| SS Dingle | Merchant Ship (Steamer) | 1916 | 593 | 51.28.527 | 1.33.463 | ||||

| UC-6 | Submarine | 1917 | 225 | 51.30.107 | 1.34.706 | ||||

| SS Joséphine Charlotte | Cargo (Steamer) | 1940 | 3422 | 51.32.00 | 1.33.00 | 51° 32' | 01° 33' |

252 wrecks in total

Location data for Latitude and Longitude Degrees Decimal Minutes (5th & 6th columns) taken from www.wrecksite.eu