Kent Coast Sea Fishing Compendium |

Shingle Beaches |

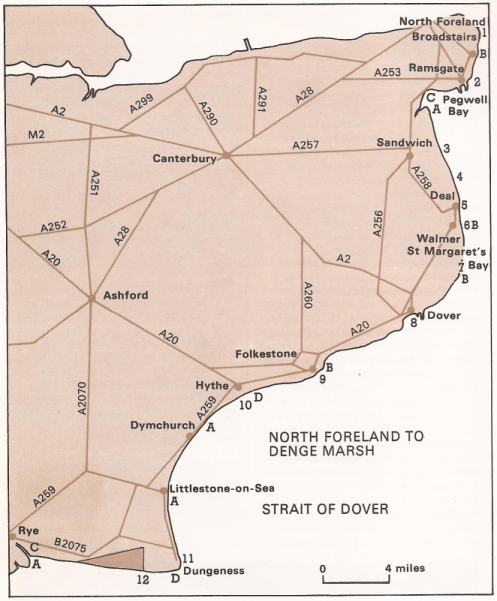

Fishing is possible along the entire stretch of beach comprising the east Kent coast from Pegwell Bay in the north through Sandwich Bay, Sandown, Deal and Walmer, Kingsdown, St Margaret's, Dover, Folkestone, Hythe and Dungeness in the south. Much of this beach is steeply banked shingle going onto sand.

"The Sea Angler Afloat and Ashore" (1965) Desmond Brennan at pages 19 & 20

The Sea

Beaches vary greatly in their nature and extent but break down roughly into three main types: (i) shingle beaches, (ii) beaches of small gravel and coarse sand, and (iii) flat firm beaches of muddy sand. Beaches are often a mixture of these main types but the predominant character of a mixed type of beach determines what food and what fish are likely to be present on it.

Shingle beaches are usually very exposed and subject to heavy surf or wave action which builds up steep banks of shingle. They are usually found along a rugged coastline but can also be formed as spits in estuaries, or bays or near headlands where strong tidal currents build them up. The shingle may be composed of small pebbles, or rounded stones as big as six inches across and usually has a very steep slope. Owing to the constant movement of the pebbles caused by wave action it is the most unstable of shores. On account of this and also because it cannot hold water, nothing either plant or animal can live on or within the shingle. The fact that there is no food on this type of shore does not mean it is not worth fishing. These types of beaches usually drop off steeply into deep water or are washed by fast tides or strong currents. Small fry or sand eels are often plentiful off these beaches either having swum in against continued offshore winds or having been channelled along it by strong tides or fast currents. In these conditions there is often very good fishing for mackerel, bass, sea trout and tope and in winter time cod. On the whole, however, this is the least productive type of beach.

Sandown (i.e. the 5½ mile stretch of beach from Sandown Castle to Pegwell Bay, the river Stour estuary), Deal and Walmer beaches are predominantly type (i) shingle beaches but include sections of type (ii), particularly after a major storm event during which the surf can denude the beach of its shingle between MHW and MLW.

To the north, Sandown beach gives way to a smooth, sandy seabed in the nature of a type (iii) beach between Sandwich Bay Estate and Pegwell Bay.

Fishing a Shingle Beach

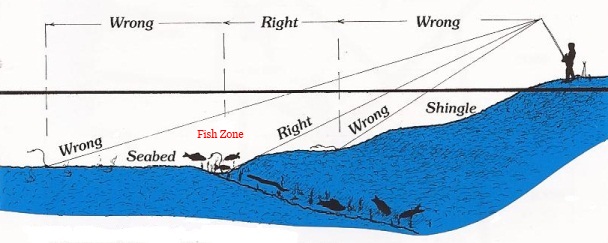

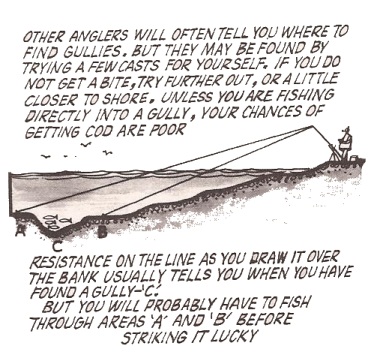

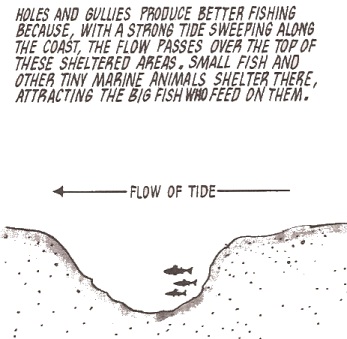

Although shingle beaches are barren, lacking food to attract fish, anglers will catch good fish from such beaches when casting a suitable bait into the gulley where the sandy or muddy seabed meets the shingle, being the zone where the fish look for food.

"Hooked on Sea Angling" (2011) Martin & Dave Beer

|

|

"The Sea Angler Afloat and Ashore" (1965) Desmond Brennan at pages 20, 21 & 22 (cont)

The Sea

The second type of beach is also an exposed one, subject to surf and to the surges of the open sea. They are often extensive, backed by rolling sand dunes and in places by banks of shingle. Near low water mark these beaches are often comparatively shallow, sloping gradually up towards high water mark, then rising quite steeply. The coarse gravelly sand high up on the beach is not fully stable, being subject to heavy surf, but it is much more stable than shingle, it retains water and contains abundant if specialised life, e.g. sand hoppers. This loose coarse textured type of sand is often the home of sand eels, a very important food for may fishes, while lower down on the strand and below low water mark the sand may be more stable and more productive of life. Smelt may also be present on these beaches and in summer small fry. This type of beach can provide excellent surf fishing for bass which are often plentiful and at times shoal after sand eels and fry along these beaches. Flounders are usually plentiful and sometimes small turbot, plaice and other flatfish. If there is a fair depth of water close in, tope can often be taken; and in winter the rough water along the beaches may prove attractive to cod.

The first two types of beaches are usually called storm or surf beaches and differ greatly from the last type of beach which is only found in sheltered conditions where it is not exposed to heavy wave action. These are flat or gently sloping beaches composed of firm muddy sand, corrugated and rippled on the surface by gentle wave action. On account of their small slope they are extensive beaches where tides advance and retreat a long way and there is no great depth over these beaches when the tide is in. They are the most stable of beaches and very rich in food. There are usually extensive beds of lugworm and cockles, whilst the pools and channels left by the receding tide are full of shrimps, gobies, baby flatfish, mullet, fry, small crabs and other creatures. Down near low water mark there may be beds of razor fish. As would be expected, such a rich larder of food would not be ignored by hungry fish and on the tide, bass, mullet, sea trout, gurnards and flatfish swim in over these beaches seeking a variety of food organisms. This type of beach provides excellent fishing provided that you know where, how and when to fish it.

The foregoing is a very general classification of beaches. No two beaches are the same. A beach is often a combination of two and sometimes even of the three types. The angler must get to know the characteristics of each, to figure out the species of fish he is likely to catch, the most favourable spots and state of tide, and the best methods, tackle and baits to use.

Fish are taken occasionally all along a beach but some portions are more productive than others. Some stretches may be completely barren of fish and it is a waste of time to fish them. Fish will be found where there is plenty of natural food for them so never fish blindly, but think about your fishing before you start. Study your beaches. Walk along them at low water, noting the likely places. You will find that if you make a point of studying your beaches at low water you will be well repaid by better fishing.

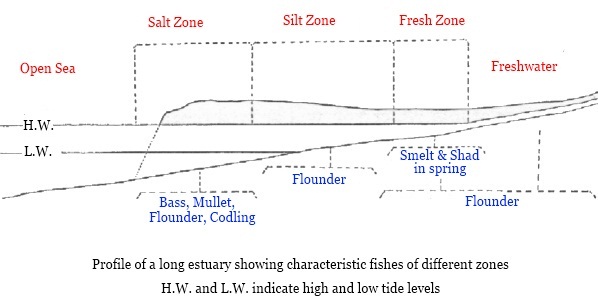

There is one last type of shore to mention and that is the muddy shore. This type of shore also has its distinctive fauna and distinctive location. It is the typical bottom of harbours, creeks and estuaries and of the three the creeks and estuaries usually provide the more interesting fishing. Estuaries vary in size from small creeks into which little streams flow, to large harbours which are the tidal mouths of major rivers and may be many miles wide and a score or more miles in length. These large harbours, really arms of the sea, may be difficult to recognise as estuaries, possessing as they do in many cases large amounts of rocky and sandy shores.

This type of shore is found in the lower part of large estuaries and is entirely marine in character. It differs from the open sea in that on the ebb tide the water may be brackish and discoloured and the bottoms vary from sand and gravel to mud depending on the swiftness or sluggishness of the tides and currents. Bass, mullet, flatfish and codling are typical fish of the lower estuary and tope, skate, rays, mackerel and many other marine species may be caught.

Farther up the estuary the water is brackish, thick with silt and the bottom muddy. This is the middle estuary and the limit of the respective ranges of both freshwater and marine organisms and fishes. Typical fish of the middle estuary are freshwater eels, flounders, slob trout and perhaps mullet and bass.

The upper estuary is entirely fresh in character although still influenced by the movement of the tides which twice daily stop and reverse the seaward flow of the river causing the water level to rise. The sea is still represented here for flounders are quite at home in fresh water and even mullet may ascend this far and linger awhile. Such migratory sea fishes as salmon and sea trout will pass through the upper estuary and it is here at the limit of the tidal influence that shad in some rivers will spawn.

The three major zones e.g. the upper, middle and lower estuary are readily discernable in the larger estuaries but in the smaller ones their extent will naturally be less and one i.e. the marine, may predominate. It is the lower estuary that provides the sea angler with bait but all the reaches of an estuary can provide him with fishing.

Editor's Note: This classification of beaches can also be found in Chapter 8 (Bass) on pages 158 to 160

"Sea Fishing" (1911) Charles Owen Minchin at pages 214 & 215

Chapter XV

Fishing from Rocks, Piers and Beaches

… On these shingle beaches the gravel slopes irregularly down at a more or less steep angle from high-water mark to near low-water level, and from that point the sand, pretty clear of stones, lies flat or with a very slight slope for some distance out. It is at or near the angle between the shingle and the sands that the cod nose about for their food, the soldier and shore crabs, small flat-fishes, whelks &c which abound just there, so that if the fisherman with his rod and reel can cast two or three well-baited hooks there or thereabouts, he has just as great a likelihood of getting a fish as by violently heaving out a score and a half of hooks on the sands, where fish - codfish at all events - are more scattered.

It is easy to measure the necessary length of the cast at low water when the distance can be accurately estimated, and then return a trifle before high-water time and put it to the test of practice, remembering that no great harm is done by casting too far out, because the wash will soon bring the lead inshore, and that it is utterly futile to fish among the shingle for the fish will not come up so high unless possibly the spot may have been ground-baited by cleaning up some boat's capture at the last low-water time.

"Sea Fishing Simplified" (1929) Francis Dyke Holcombe & A. Fraser-Brunner at pages 43 & 44

Chapter VII

Pier and Shore Fishing

As far as shore fishing is concerned, this is a branch of the sport which, even today, has not been as thoroughly exploited as it might be. It has been mentioned previously that a good many bass have been caught from the shore on the south coast; some good fish have been taken at Bexhill, Eastbourne and other places, and if you are staying anywhere along that coast, and decide to try shore fishing, the bass is the fish that you should have in mind. Use … Wadham's paternoster or flowing trace, pattern 3.

Baits should be as previously mentioned, and a piece of bloater might be tried; if you are baiting with mackerel, put on a generous slice.

Spring tides are best, and you will have more chance of success if there is some sea on. Fish the last three hours of the flood and the first of the ebb.

Long casting is not generally necessary to success, and if you can get out 30 yards or so this will usually be sufficient; use a lead similar to that employed for pier fishing.

It is not at all a bad plan, if you like to take the trouble, to ground bait a likely and secluded place on the shore, if you can find one, by putting some fish offal, chicken entrails, defunct lugworms, etc., into an old sack, and anchoring it with some large stones somewhere about the half tide mark.

And now it only remains to wish you tight lines and heavy catches, whether you fish afloat or ashore.

"Modern Sea Fishing" (1937) Eric Cooper at pages 38, 39 & 44

Shore Fishing

Shingle beaches have in most cases a good depth of water right inshore, and though the ability to cast long distances will at times be advantageous, it is usually only necessary to get out some 15 to 20 yards. Many occasions will be met with when the fish are not half that distance away.

The principal fish feeding on shingle beaches are cod and bass, the former on the East and South-East Coasts during late autumn and winter, and the bass on our South Coast in the summer.

A good run of tide will generally be found where there is deep water and a fair amount of lead will be necessary to hold bottom. The finer your line the less lead you will need.

A two- or three-hook paternoster will be the best tackle to use for this shore fishing …

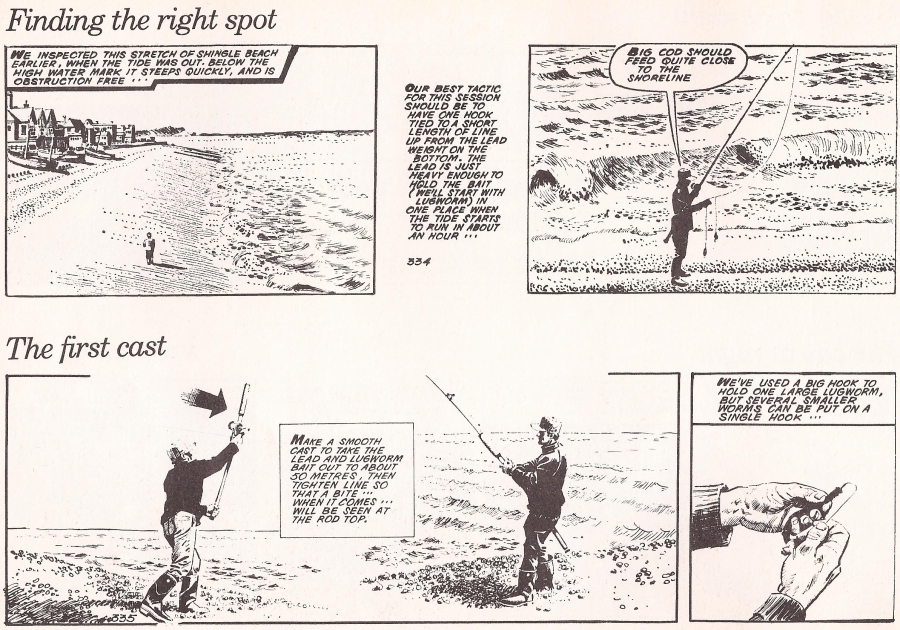

To decide on the most likely place to take up your position on an open beach, an inspection of the ground at dead low water will be of great assistance. No reason may be apparent at high water why the fish should select one area more than another, but in practice it will be found that they do.

If the inspection gives no clue to the problem, the chart should be consulted. Some slight alteration in the depth or a small patch of rough ground will probably be found. If you have a 1-inch Ordnance map with you, this will possibly show where fresh water is percolating through the pebbles. Such spots should be given a trial.

No baits will be found on a shingle beach; starfish will often be caught, but they are useless.

"Bass: How to Catch Them" (1955) Alan Young at pages 54, 55 & 56

Chapter IV: Methods

From Beaches

… steep-to beaches can be fished with float or spinner, but on the majority of beaches, paternostering and ledgering are the only practicable methods. Bass certainly come into really shallow water with the tides, but even water only 2 or 3ft deep needs a fairly long cast on most of the sand or sand and mud shores. "Bass water" is out of reach on these by any other methods unless a boat is used. In the cold months they are the most likely type of beach for bass. Although other methods of fishing provide (in my opinion) greater sport, there can be no doubt that far more bass of from 2lb upwards are taken by paternostering and ledgering than by all other means put together …

Steep-to Beaches

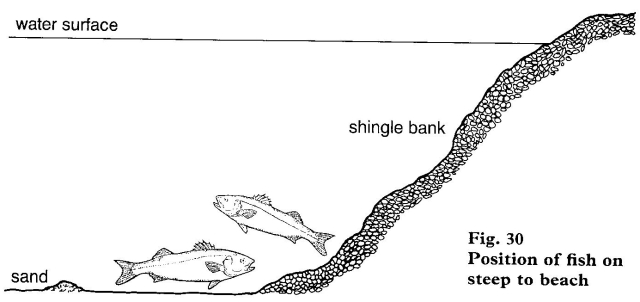

On these beaches many good casters cast too far when bass fishing. Bass are likely to be close in, and particularly likely to be exploring the base of the step or steps in which the beach falls. I believe they incline to move parallel with the shore, or at least in the direction of the flow of the tide, and thus a long cast into deep water puts the bait both below and beyond them.

I have found that a good method where there is no foul ground is to cast rather further out than is strictly necessary, i.e. into water just beyond the beginning of the breakers. Let the weight sink and tauten the line. Pause for two or three minutes and pull the weight in a yard or so. Pause again, and continue the recovery until the baits are fishing in what is considered to be the right position, and then settle down to fish it until the changing level of the tide or the need to examine the baits makes it necessary to reel in.

Gently-Shelving Beaches

It is well to survey these at low tide, for in the vast area of an almost featureless shallow beach it pays to find those places which may be particularly attractive to bass. Note the patches which are most thickly covered with the "hole and wormcast" signs of lugworms; ridges of weed which harbour crabs; channels behind rocks or other obstructions; and places where freshwater scours out a shallow depression on its way to the sea. Note should also be made of any timber or metal constructions that are covered at three-quarter tide or earlier - groynes, piles, outfall pipes, etc - for such structures, scarce though they may be, are likely to attract bass.

This low-tide study of the beach may be used not only to choose places which can be fished with advantage as the tide advances, but to pick out (and fix by objects above the tide line) areas in which it is dangerous to cast because of obstructions likely to foul the tackle.

On these gradually sloping beaches the aim should be to place the bait in from 3 to 4ft of water, where it is likely to be found by bass in their advance with the tide. The distance at which this depth is to be found differs with the slope of the beach.

On beaches where the gradient is so slight that the tide goes out for well over a mile … bass fishing had best be forgotten unless a boat is available.

"The Modern Sea Angler" (1958) Hugh Stoker at pages 53, 54 & 60

Chapter Five

Shore Fishing

… One very important point which is frequently overlooked is the need to carry out a preliminary survey of any hitherto unfished shore before actually wetting the tackle. Fish naturally congregate in those areas where there is an abundance of food, and for this reason the rod-and-line sport tends to vary considerably from one part of a beach to another. On most stretches of shingle or sand there are usually a few very localized spots which provide quite excellent results; whilst elsewhere, possibly only 50 yards away, the fishing may be mediocre, or even a complete waste of time.

Obviously, therefore, the would-be shore angler must first of all study the feeding habits of the fish he is going to try for. Where the shore consists of a flat expanse of mud or sand, many species work their way in with the tide in order to prey upon the worms and other small marine creatures which inhabit this type of coastline. To discover the richest feeding grounds it is necessary to visit the shore at low tide, when it is a simple enough matter to note those places where the worm-casts or clam-burrows are thickest.

Wave-washed rocks are another source of food for many kinds of mollusc- and crustacean-feeding fish, and a line cast out at a point where a beach of sand or shingle adjoins a patch of broken ground will generally produce good results. Here again, though, low-water prospecting is essential; and for preference this should be carried out during a very low spring tide.

If the shoreline is backed by cliffs it is possible, when the sea is clear and the tide is low, to gain an excellent gull's-eye picture from the cliff-top of the sea-bed formation - the rocky areas showing up clearly as dark patches against the lighter tawny hue of clean ground. Don't try to memorize all the likely stances; instead, take a pencil and paper with you and draw a rough sketch-map, marking on it the position of the underwater rocks in relation to various outstanding permanent features on the shore, such as landslips, longshore trees and shrubs, capstans, cliff-top fences, and so on. At the same time, remember that you may wish to fish after dark, so wherever possible choose landmarks which will be visible from the beach on a moonlit night.

Shingle beaches usually shelve much more steeply than the sandy variety, and in consequence, when fishing the former it is seldom necessary to cast out very far in order to get the baited tackle into fairly deep water. For this reason a shingle beach offers the best possibilities for the novice shore angler; whilst at the same time permitting the use of a general-purpose rod or reel, not specifically designed for shore casting …

… When selecting ground tackle for shore fishing, it is worth remembering that every baited hook carried on the trace imposes some extra wind resistance when casting out. In the case of small, compact baits this resistance may be very slight, but experiments have shown that a large fish bait, of the type commonly used for bass or conger, is capable of curtailing a cast by several yards. Therefore, on gently shelving beaches, where long casting is often essential, more than one hook can at times be an unnecessary encumbrance. Certainly, there is little point in using two hooks when both of them are of identical size and carrying similar baits.

If two or three hooks are used - and there are plenty of occasions when it is practicable to do so - it is a sound general practice to place on one hook an oily fish bait for its smell value, and on the remainder a selection of 'close-interest' baits, such as soft crab, squid, ragworm, prawn, etc. Generally speaking, it is best to use baits which occur naturally in the locality, although that most highly prized quarry of the surf fisherman - the bass - often gives the lie to this rule. This species is even partial to pieces of kipper and bacon rind. Among other fish regularly taken by the shore angler in the appropriate season may be listed the codling, pouting, conger, wrasse, spotted dogfish, rockling, and flounder …

"The Sea Angler Afloat and Ashore" (1965) Desmond Brennan at pages 160 to 162

The Fishes of the Sea

Bass

On steep shingle beaches there is a point where the slope of the beach suddenly drops off into deeper water. When the tide is in, it is along this shelf that the fish will forage and that is where your bait should be placed. In moderate or light surf such beaches may be fished with light bottom gear, for long casts are not essential as the bass may be no more than a few yards from the edge. The same applies to spinning. Do not cast straight out but rather cast at a tangent so that your bait will fish along the shelf and just behind the surf where the bass are feeding. Fish places where the tide or current sets in against the beach or is set off by some projection. Food will be swept along and concentrated in these places and you can also use the run of water to trot a float to places you cannot fish on the bottom or reach by casting.

In beach fishing, as in any other form of fishing, look for places where the fish will come to you, rather than go searching for them. Bass will forage along the length of a beach so that both ends are obvious places to try. There is a sweep of tide along most surf beaches and as bass tend to swim with the tide this narrows down your choice. One end of a beach may be better on the flood, the other on the ebb or perhaps at half flood or half ebb. By fishing these places consistently up and down the tide you will soon get to know the times during which they fish best.

"Pelham Manual for Sea Anglers" (1969) Derek Fletcher at page 111

Study

Shingle shores are more of a problem because these are often devoid of food for feeding fish. However after dark many large fish are taken when they are on the move. Usually the most productive spots are seaward spits of shingle where the surf action is the greatest. Where a shingle beach shelves deeply, float tackle is recommended, a method which allows the bait to explore a greater expanse of water.

"Sea Fishing" (1969) Clive Gammon at pages 60 & 61

… the shingle beach, steep-to and with a significant depth of water a very short distance offshore, is characteristic of the Channel coast and of the littoral farther north.

Such beaches, because of their configuration, require quite different techniques and tackle from those of the west. In addition, the species which haunt them are different: cod, dabs and sole replace bass and flounders. No hard and fast rule can be laid down. Bass will come on to shingle beaches sometimes, and cod will turn up in the western surf: but not typically.

The chief problem of the shingle beach is that the shingle itself is barren. The sandworms, crustaceans and molluscs that live in sand are completely absent, so why should fish approach shingle beaches at all ?

One might reasonably ask what there is in the way of food to attract them. This problem is perhaps not easy to solve at once; but it is cleared up when the beach is uncovered at low spring tides. It will then be seen that the shingle bank gives way to flat, hard sand towards the limit of the tides. This sand holds quantities of food, which is often washed out by wave action, especially, of course, in big seas. The steep shingle bank and the flat sand meet at an angle - a kind of natural gutter where food accumulates and fish feed.

Hence the important thing to remember when you are fishing a shingle beach is to aim to throw the bait as nearly as possible into this gutter.

This is the area in which food is to be found, and where the fish expect to find it. So it is also the area in which the bait must be placed. A bait landing on the shingle itself will not be found: the fish will not hunt beyond the sand line. A bait thrown out on to the clean sand may be taken, but the chances are greater if the bait is snugly in the gutter.

At Dungeness, which may be regarded as a classic example of the Channel shingle beach, a tidal eddy at the Point forms what local anglers know as "the Dustbin". It is a kind of natural dumping ground for small marine animals.

On shingle beaches, long-distance casting techniques are vital for success in placing the bait.

"Sea Fishing for Beginners" (1970) Maurice Wiggin at pages 109, 110 & 112

Chapter VII

Fishing from the Shore

But of course not all beaches are gently shelving sand. There is the steep-to shingle beach, any amount of it. This is a very different proposition. Shingle, as is well known, is sterile from the point of view of fish food. The stones composing it take a fearful hammering from the sea, nothing can live in them. So it's not a lot of use letting your bait lie on the pebbles.

Nor, though, is it a lot of use hurling your bait out on to the sandy bottom which lies beyond the shingle. For the fish ain't all that likely to be swanning around on it. Where are they, then? They are crowding into the bait parlour or snack supermarket which is strictly localised at that very point where the shingle gives way to the sand. There and virtually nowhere else are they to be found. And for why ? I'll tell you why, comrade and brother-in-arms. They are huddling and elbowing there, in the ditchy little bit of a gully at the junction of sand and shingle, because it is precisely here, at the angle between the shingle bank and the sandy gentle bottom, that food galore is put at their disposal. What happens is that the waves wash and knock the abundant small food life out of the sand - and hurl it landwards until it is abruptly stopped, halted and anchored by this slope of shingle which rises from the relatively level sand bed. So a fair mass of food accumulates just at that point, I should perhaps say that line where sand and shingle meet. Fish have had longer to find this out than you have: they've been doing it for countless generations. So they'll be there, nosing around. And your bait had better be there, too.

Just how far out the shingle changes over to the sandy bottom, needless to say, is a fact which you simply have to know. Kind local anglers may confide in you. Unkind local anglers may conceivably try to mislead you. You may copy their casts, though of course you may be wasting time by doing so - they may not be locals at all, they may be strangers as clueless as you. No, the one certain way of finding out is to have a real good gander at dead low water. Generally speaking the junction is possible to spot - it may be the low-water mark itself, though not necessarily. But you can always consult an Admiralty chart, ask at the Town Hall, or even take a swim.

Find it you must. On such a beach, it will make all the difference to your sport to know where it is. True, you always stand quite a fair chance of catching the odd fish on the sandy reaches well beyond the junction of sand and shingle. But fewer, and fewer by far, than if you can hit on the line itself.

The right spot isn't always 'a mile' out, as at Dungeness with its famous, or infamous, 'Dustbin'. It may be close in: all depends on the steepness of the beach, the underwater geography which is so important, and so interesting, to learn.

Too often it is a devil of a distance. Keep plugging away until you have that 100-yard cast under your belt. In judo terms, your Black Belt.

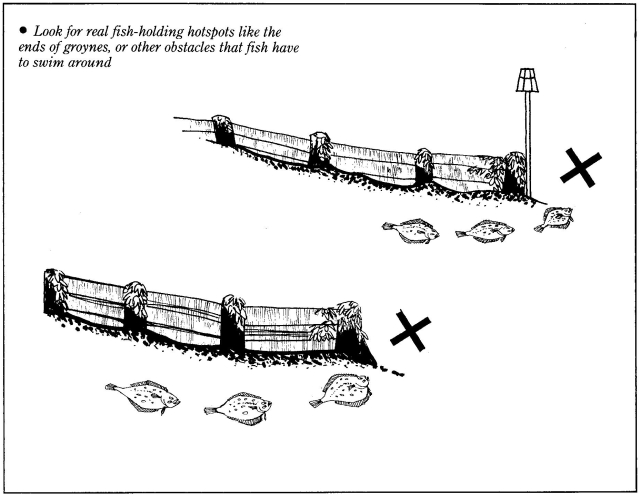

Don't omit to make full use of such heaven-sent aids to fish and fishing as that curious invention of man, the groyne. Wherever groynes have been built out to sea in an effort to resist erosion, use them - use them at all times, but especially after rough weather, or even during rough weather. It will not have escaped your agile mind that the sheltered side of a groyne does not only provide low-water shelter for sunbathers and picnickers: it provides high-water shelter for fish, from the hammer and pressure of the tide. When a heavy sea is running, there are havens of relative peace to be found right up close in on the sheltered side of a groyne. Note which way the sea is running - it often runs not straight in, but at a sharpish angle to the land - and use the groyne accordingly. You can often fish right up against the woodwork (or stonework) with great success. But this is real heavy-weather advice.

Some anglers stand on top of the groynes, thereby obtaining a pleasing illusion of effortless superiority. I doubt if it is really worthwhile, apart from the not in-considerable danger of being washed away in the furious undertow should you lose your footing. You don't need the extra casting distance if the fish are coming in literally under your feet, and I've never thought it too good an idea to stand over the fish. It isn't quite so important, to practise the time-honoured fresh water doctrine of 'fine and far-off'; but sea fish aren't all idiots, it's still better to 'study to be quiet', absurd though such advice may seem when you can't hear yourself shout for the noise of the wind and the waves. But a habit of dissimulation, of caution and stealth, is a good thing to acquire. In fishing, I mean: not in the human dealings of life, where a frank and manly straightforwardness is much to be preferred. Though I don't know …

"Modern Sea Angling" (1971) Alan Young at pages 16 & 17

On a beach where the shingle drops suddenly to a considerable depth, long casts are inadvisable, for many species of fish, including bass, come close to the foot of the ridge, for it is there that food is to be found.

On the gently sloping beach gumboots or thigh waders are an advantage, for they gain another two feet or so of depth. On shingle beaches with a sharp drop they are dangerous, for in moments of excitement it is easily possible to step into deep water, and shingle does not provide a firm foothold.

"Sea Fishing (Learn Through Strips)" (1973) John Mitchell (London Evening News) at page 32

"The Sea Angler's Guide to Britain and Ireland" (1982) John Darling at pages 5, 12 & 13

Foreword (Michael Fish, London Weather Centre)

As I seem to have a reputation for forecasting bad weather and even by some, held responsible for it, I feel I must impress on anglers, if nothing else, that it is essential to seek meteorological advice before contemplating a fishing trip … Give the barometer a gentle tap, for instance. If it shoots down think twice before going: even more so if the cloud is thickening and lowering. Sometimes a rapidly rising barometer can spell trouble, too, as strong winds can come along just behind a depression. As a final piece of advice, do take a radio with you, as this will enable you to keep an ear tuned for the gale warnings and regular shipping forecasts … If you hear a gale described as 'imminent' that means it will occur within six hours, 'soon' means between six and 12 hours and 'later' means more than 12 hours away. Anyhow, that's enough preaching from me … [1]

[1] Editor's Note: Michael Fish who, in a weather forecast at 21:30 on the evening of 15th October 1987, informed millions of viewers that "earlier on today apparently, a woman rang the BBC and said she had heard that there was a hurricane on the way. Well if you are watching, don't worry there isn't …" The worst storm in living memory (a 1 in 200 year event) occurred during the early hours of 16th October 1987, with storm force 11 'hurricane-strength' winds. As dawn broke, 18 people had lost their lives and 15 million trees had been uprooted. In an interview with the BBC Michael Fish explained that "there were remarkable rises in temperature, in some cases up to 10, even 12 degrees C in the space of only 20 to 30 minutes. Likewise we had some huge rises in pressure - of 25 mille bars in some places - again in just a few minutes. Although you think of low pressure causing strong winds - it wasn't. It was an extremely rapid rise in pressure that was more the cause of the winds than anything else". Next time, Michael, practice what you 'preach' and give the barometer a "gentle tap" …

Kent

There are some dramatic changes in the shore line as one works south along this section of the Kent coast. The rocky ground north of Ramsgate contrasts sharply with the shallow sands at Pegwell Bay. The water deepens slightly south of the Stour estuary, round the broad sandy sweep of Sandwich Bay, a place many anglers visit if sou'westerlies at Dungeness make fishing impossible. Around Deal, the beaches are steeper still, of shingle, mixed rock and sand below the water line, which in turn becomes very reefy if the South Foreland area. This continues round to Folkestone, becoming sandier at Hythe, and more shallow again at Dymchurch before the dramatic depths and tides at Dungeness Point. The water is deep along Denge Marsh but is shallower again at Camber and towards Rye Harbour.

The main fish species caught from the shore are cod, flounders, dabs, pouting and whiting in winter; bass, conger eels, small tope, mackerel, scad, garfish, small pouting and whiting, plaice, sole, some cod and some dogfish in summer. Many of the locals fish for sole and bass in summer, big dabs and large cod in winter.

Mullet are common in the harbours at Ramsgate, Dover, Folkestone and Rye and in the Stour and Rother estuaries. These are mainly thick-lipped, but thin-lipped mullet are found in the Rother and a few golden grey mullet are taken from the beaches.

Boats from Ramsgate, Deal, Walmer, Folkestone, Dungeness and Rye Harbour all provide good fishing in winter for big cod until late December when huge sprat shoals move in and blot out everything but small bottom feeders. Offshore grounds provide good tope, spur dogfish, flatfish, some rays and black bream and smaller species in summer. The wreck fishing can be very good for medium pollack and ling and for good cod in summer. The Straights of Dover have several large sandbanks like the Varne, which also provide good cod and infrequent turbot fishing in summer.

Slipways are available for those with boats on trailers at Broadstairs (4 hours before and after high water); Ramsgate harbour (not at dead low water); Deal Rowing Club; Dover (all states of the tide); Folkestone (all times); Sandgate, behind the rowing club; Princess Parade, Hythe, and at Rye Harbour (not at dead low water).

The tides, especially to the north of Dover, run hard and in a confusing pattern. The visitor is advised to obtain expert advice for setting out. High tide times are 2½ (Deal) and 2¾ (Dover) hours before London Bridge. Tidal Streams are very complex.

There are thriving sea angling clubs at: Dover SAA, 14 Priory Road, Dover (Tel. 01304 204772); Deal AC at 13 The Marina, Deal; Deal and Walmer AA at South Toll House, Deal Pier.

Bait Areas

A Plenty of blow-lugworm at Pegwell Bay. Dig it by trenching, but moat diggings to keep out surface water. Keep an eye open for hovercraft. Lots of good black lugworms which should be dug individually with a proper lugworm spade. Dymchurch and Dungeness, Galloways and Rye.

B Plenty of peeler crabs among the rocks in spring and autumn, also piddocks and rock worms here.

C Small harbour ragworm from the Stour and Rother estuaries.

D Storms often wash in large numbers of razorfish etc at Hythe and Dungeness.

"Fishing for Bass: Strategy & Confidence" (1989) Mike Thrussell at page 85

8. Specimen Fish

… I find that open beaches rarely produce fish of above-average size. Your only chance is to fish in very rough weather and heavy surf, for, despite what many anglers say, it has to be a mighty sea before bass will move offshore. Try two rods, one out as far as you can hit it and the other close in. Peeler or mackerel make the best baits, though king ragworm is worth trying. The deeper beaches, such as … Dungeness in Kent, throw up good fish in the autumn. Use only big baits and aim to place them where the shingle of the rising bank meets the level sand of the sea bottom, for it's here the majority of the food will collect (see Fig. 30).

"Sea Fishing: Expert Advice for Beginners" (1991) Trevor Housby at pages 21 & 22

Steep to Shingle Beaches

A steep to shingle beach drops rapidly into deep water. Some of the finest fishing beaches in this country - Dungeness in Kent, Milford shingle bank in Hampshire and Dorset's magnificent Chesil Beach - are of this type. Fish are present on a year-round basis. Although fish species may change with each season, the fishing remains good. For example, Chesil Beach during winter can produce plenty of big cod. Cod catches are usually interspersed with whiting and bouts of large spurdog activity. However, during spring, summer and autumn catches of bass, sole, conger, tope, mackerel, garfish and recently the normally subtropical trigger-fish, are common. Thornback ray and small-eyed ray also occur.

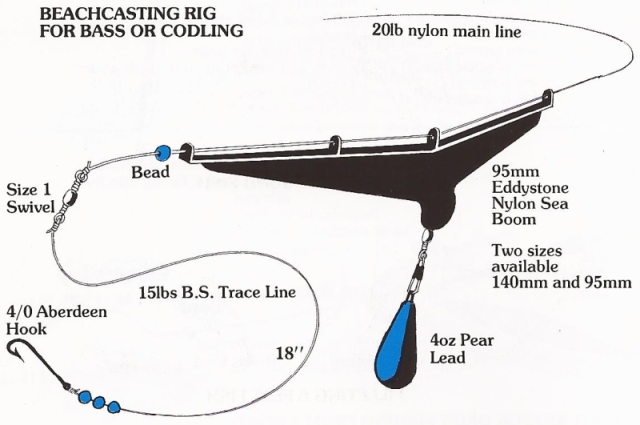

These beaches are often subjected to strong tidal activity. For this reason and because of the average large size of fish present, a heavy beachcaster's outfit is widely used. A rod capable of casting a 6-8oz lead is the most popular. Long casting is seldom necessary unless the bait has to be cast to a specific fish-holding area. Fish usually expect to find most of their food at the base of the beach drop-off. If an offshore gully can be located it may prove to be extremely productive. Even a 12in deep trench can act as a roadway for patrolling fish. Regular anglers tend to prefer multiplying reels to fixed spool reels, which have certain limitations when hooking a big cod or good-sized conger.

Natural baits used on steep to shingle beaches tend to be larger than those used on shallower beaches. Mackerel fillets, whole sprats, calamari squid and crab are among the popular baits at Milford shingle bank and on the Chesil Beach. Further east at Dungeness, worms (especially black and yellow tailed lugworms) are the real killers. Normally four to six of these worms are crammed onto a hook to make a large very edible bait loved by cod and whiting. Another successful bait used particularly when ray and conger are on the move is a fresh whole pouting or a fillet of pouting. It must be fresh, though, in order to be effective. Pouting are common along any steep to shingle beaches.

During the summer months vast shoals of mackerel may sweep along these beaches. Many anglers then switch from natural baits to strings of four to six feathers, which are cast out as far as possible and retrieved at speed. Beach mackerel are often suicidal and can be caught in huge numbers.

"The Complete Book of Sea Fishing: Tackle and Techniques" (1992) Alan Yates and Jed Entwistle at pages 48 & 49

6. Beach and Promenade Fishing for Bass, Cod, Rays and Flatfish

The venues and tackle

The storms themselves tend to have a significant effect on the fishing from such shores, with huge breakers, waves and wind-driven swell gouging shellfish, worms, crabs and eels from their homes in the sand. Even the smallest waves prompt a con-tinuous stream of dislodged food items for fish, and despite looking barren, many of these flat, sandy storm beaches are a mass of burrowing creatures. A storm during the biggest spring tide can often smash a complete sandbank colony of razorfish or cockles to pieces, thus providing a natural ground-baiting effect to which the fish flock. During such times the fish can be as close in as the trough behind the main breaker, feeding at the base of the most powerful waves as these gouge out the sea-bed. In calmer times the far side of a sandbank or deep gully 100 yards (91.4m) or more offshore may be the place to find the fish, where a minimum of wave action will provide a food source. Most storm beaches seem quite featureless, and give little away in the way of clues as to where the angler might find fish; however, there are a few things to look for. Groynes, concrete cliff aprons or promenade supports, for example, force the fish to make a detour, and the end of such an obstruction is always a hotspot. Pick the longest groyne and fish close to its end. Gullies and sandbanks can only be seen at low water, but their presence at high tide is often revealed by wave action and surf, whilst patches of coloured water may reveal mud or sand being disturbed.