Kent Coast Sea Fishing Compendium |

Cooking the Catch |

A chronology of fish cookery extracted from sea angling books and fish recipes

published during the 600 year period from 1390 to 2019

Contents

- "The Forme of Cury" (1390) Richard II

- "A Book of Cookrye" (1591) A. W.

- "The Art of Cookery made plain and easy" (1747) Hannah Glasse

- "American Cookery" (1796) Amelia Simmons

- "The American Frugal Housewife" (1832) Lydia Maria Child

- "Fish, How to Choose and How to Dress" (1843) William Hughes "Piscator"

- "Modern Cookery for Private Families" (1845) Eliza Acton

- "What Shall We Have for Dinner ?" (1851) Catherine Dickens ("Lady Maria Clutterbuck")

- "A Practical Treatise on the Choice and Cookery of Fish" (1854) William Hughes "Piscator"

- "The Book of Household Management" (1861) Isabella Mary Beeton

- "Sea-fishing as a Sport" (1865) Lambton J. H. Young

- "Soups and Dressed Fish à la Mode" (1888) Harriet Anne De Salis

- "The Handbook of Household Management and Cookery" (1894) W. B. Tegetmeier

- "A Handbook of Fish Cookery: How to buy, dress, cook and eat fish" (1897) Lucy H. Yates

- "Simple Fish and Vegetable Sauces" (1903) Charles Herman Senn, Brown & Polson

- "Practical Sea Fishing" (1905) P. L. Haslope

- "A Guide to Modern Cookery" (1907) Georges Auguste Escoffier

- "Fish and How to Cook it" (1907) Mrs C. S. Peel

- "How to Cook Fish" (1908) Olive Green

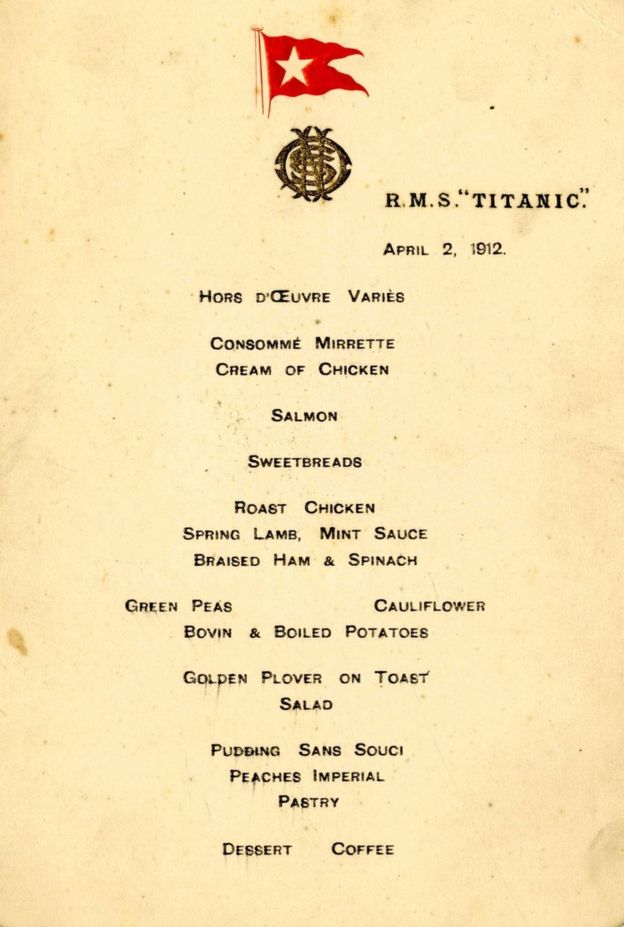

- "R.M.S. Titanic Menu" (2nd April 1912) Second Officer Charles Lightoller

- "Cookery for every Household" (1914) Florence B. Jack

- "Fish and how to Cook it" (1915) Department of the Naval Service, Ottawa

- "The Gentle Art of Cookery" (1925) Mrs Hilda (C. F.) Leyel & Miss Olga Hartley

- "Sea Fishing Simplified" (1929) Francis Dyke Holcombe & A. Fraser-Brunner

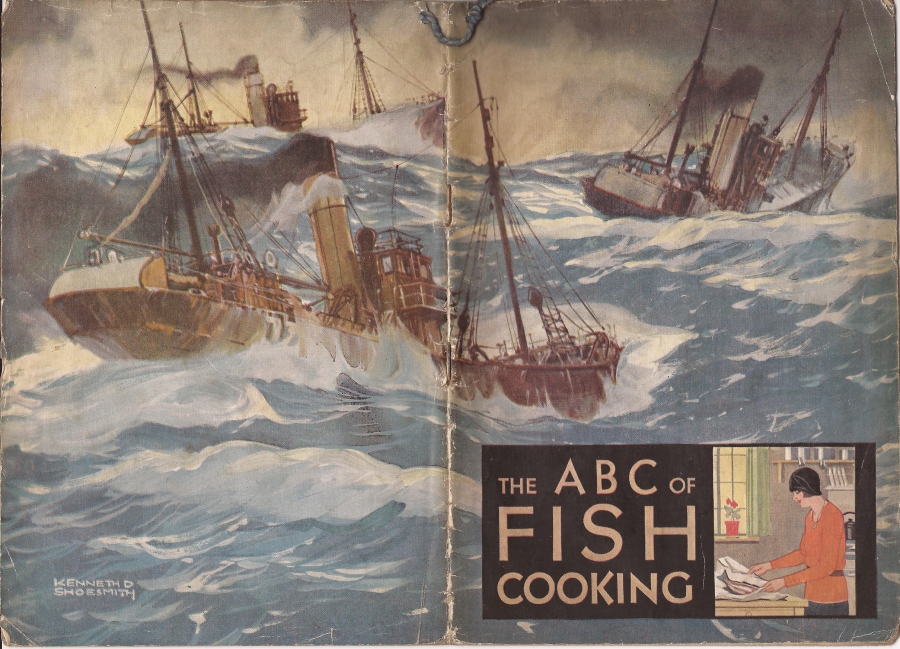

- "The ABC of Fish Cooking" (6 May 1930)

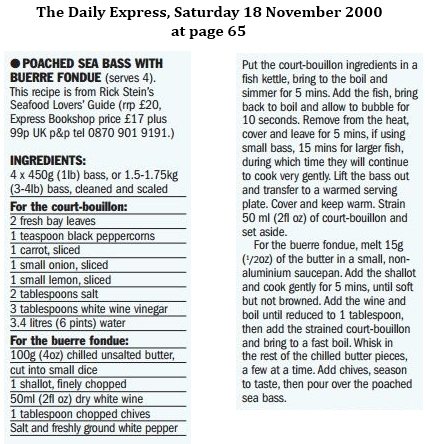

- "Daily Express Prize Recipes for Fish Cookery" (9th June 1930) Daily Express

- "A Pretty Kettle of Fish" (1935) Elizabeth Lucas

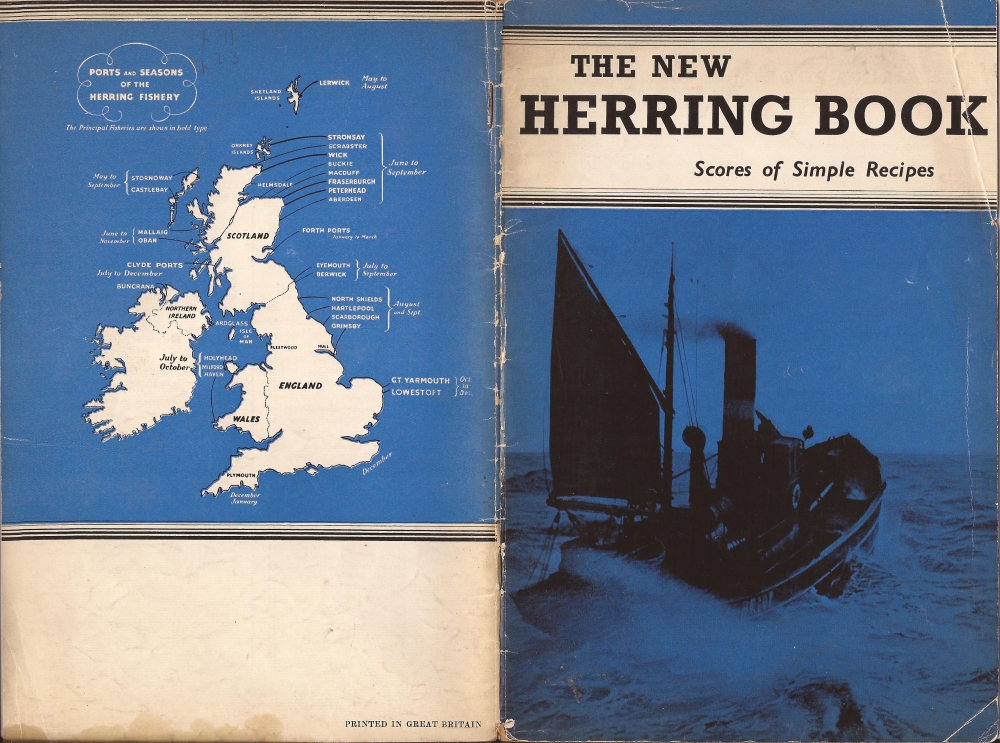

- "The New Herring Book" (1938) Mable Webb, Herring Industry Board

- "Fish Dishes specially arranged for cooking with Regulo Oven Control" (circa 1938) Radiation Publications Department

- "Inshore Sea Fishing" (1939) William S. Forsyth

- "Wartime Fish Cookery" (1943) Elizabeth Fuller Whiteman, Conservation Bulletin 27, United States Department of the Interior

- "The ABC of Cookery" (1945) Ministry of Food, HMSO

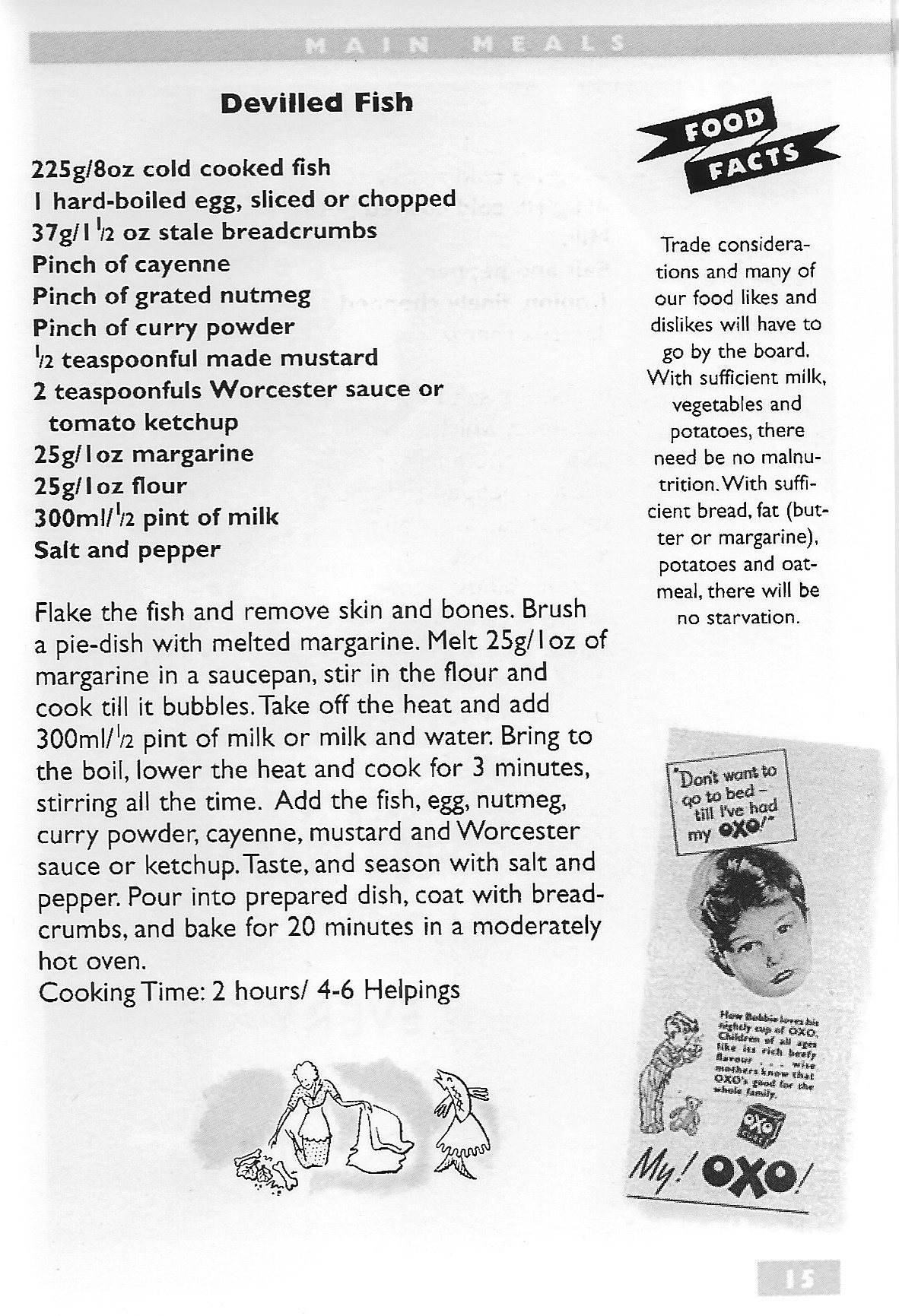

- "Devilled Fish" Dig for Victory Wartime Recipes

- "Cooking White Fish" (June 1947) Ministry of Food Leaflet No 2, HMSO

- "Fish Cookery" (March 1948) Ministry of Food, HMSO

- "Now Cook Me The Fish: 146 fresh-water fish recipes" (1950) Margaret Butterworth

- "Madame Prunier's Fish Cookery Book: 1000 Famous Recipes" (1955) Ambrose Heath & Madame Simone Barnagaud Prunier

- "A Housewife Cookery Book: Unusual and Inexpensive Fish Dishes" (1956) Rosemary Hume, Cordon Bleu School of Cookery

- "Bass: How to Catch Them" (1957) Alan Young

- "The Modern Sea Angler" (1958) Hugh Stoker (1st edition)

- "The Compleat Angler's Wife: A complete guide to cooking the angler's catch" (1964) Suzanne Mollie Beedell

- "Sea Fishing for Pleasure and Profit" (1965) Rowan Cunningham O'Farrell

- "Fish Pie … as eaten by gentlemen who made their mustachios curl" Sheila Hutchins, The Daily Express, Friday 8 February 1974 at page 11

- "How to weather the prices storm - with a squall of squid from Rockall" Sheila Hutchins, The Daily Express, Friday 26 September 1975 at page 6

- "Fisherman's Handbook" The Marshall Cavendish Volume 3, Part 74 (1979) Jan Orchard

- "The Modern Sea Angler" (1979) Hugh Stoker (6th edition)

- "Cod Fishing" (1987) John Rawle

- "Sea Fishing For Fun" (1997) Alan Wrangles & Jack P. Tupper

- "Cod Fishing: The Complete Guide" (1997) John Wilson & Dave Lewis

- "Baked salmon trout" Elizabeth David (2010)

- Sustainable Fish Recipes (2017) Anon

Preface

"The Secret Library" (2016) Oliver Tearle at pages 140 to 142

6. The Victorians

Cooking the Books

In October 1851, a book appeared that bore, on its title page, the comically absurd name of Lady Maria Clutterbuck. The book had already been through a first edition and had proved so popular with readers that a second was printed in time for the Christmas market. The book's popularity would continue well into the decade, running through five editions before 1860.

The book, What Shall We Have for Dinner ?, was, in fact, not by a lady named Maria Clutterbuck but by a housewife who bore a name far more recognizable to the 1850s public: Dickens. Catherine Dickens, Charles's wife, was its secret author and took her pseudonym from the name of a character she had played in one of her husband's theatrical productions, Used Up, in which Charles and Catherine had acted alongside each other at Rockingham Castle in 1851.

The cookbook, at least as we know it, was a reasonably recent phenomenon. Eliza Acton's Modern Cookery for Private Families had been a runaway bestseller following its publication in 1845, and within eight years it had already gone through thirteen editions. It was one of the first cookery books to provide lists of ingredients, along with the precise quantities of each. Hard though it is to believe, cookbooks before Acton's had tended to omit this information, even though it's difficult to imagine an effective recipe without them. (Richard II's Forme of Cury [11], needless to say, had not included these details.) Acton's book was also the first such work to include a recipe for Christmas pudding, another sign that the 1840s were the decade in which the modern British Christmas was created.

[11] Editor's note: The Forme of Cury (The 'Method of Cooking', cury being from Middle French cuire: to cook) is an extensive collection of medieval English recipes from the 14th century. Originally in the form of a scroll, its authors are listed as "the chief Master Cooks of King Richard II". It is among the oldest English cookery books, and the first to mention olive oil, gourds, and spices such as mace and cloves.

Catherine Dickens' book, then, was riding the wave of an immensely popular and lucrative new genre: the cookbook aimed at the burgeoning numbers of middle-class Victorians. Although it was just fifty-five pages in length and didn't provide much detail about how to put the listed ingredients together - something of a limitation for a cookbook even then - it featured an impressive number of recipes, forty-nine in all, among them spicier dishes such as salmon curry. Catherine's recipe for cauliflower cheese made with Parmesan (the Dickenses had visited Italy in the 1840s) is also included. Her book includes one of the earliest soufflé recipes in English, made with Gruyere and Parmesan: soufflé was a dish only recently made easy to cook at home, thanks to the invention of closed ranges with temperature controls.

Catherine's was also one of the first English cookery books to order the dishes along the lines of Russian service - that is, dinner served in successive courses rather than in the French 'buffet' style - which would become the preferred way in which the Victorians chose to dine by the end of the century and has remained so ever since. It was not just a culinary but a social shift: when entertaining others at dinner, the gap between courses enabled more opportunities for conversation among the guests. The modern English dinner party had been born.

| Dickens was partial to a bit of cheese and preferred to end a meal with, of all things, cheese on toast. |

What Shall We Have for Dinner ? remained popular until the end of the 1850s, and its popularity might have continued if it hadn't been for the publication, in 1861, of a book that would outsell both Catherine Dickens' book and, for that matter, Eliza Acton's. Titled Beeton's Book of Household Management, this new book would represent the last word in cookery - and a fair bit else - for the rest of the Victorian era and beyond. Thereafter, 'Mrs Beeton' would be the byword for Victorian cookery, while Eliza Acton and Lady Maria Clutterbuck would be consigned to relative obscurity in the history of Victorian dining. Catherine, who had acted alongside her husband as Maria Clutterbuck in 1851, had also meanwhile been supplanted in her husband's affections by another actress, Ellen Ternan, and Dickens had separated from Catherine in 1858. But Catherine's one book remains a revealing insight into what mealtimes at the Dickenses' were like. It also sheds light on changing attitudes to dining in nineteenth-century England.

Editor's note: Isabella Mary Beeton (née Mayson) (12 March 1836 - 6 February 1865), also known as "Fatty" to her fiancé and future husband, Samuel Orchart Beeton, was the English author of The Book of Household Management, first published in book form in October 1861, in which she warns readers that

"there is no more fruitful source of family discontent than a housewife's badly-cooked dinners and untidy ways"

yet, privately, she confessed to her fiancé:

"I shall have to go through that terrible ordeal, a dinner party … I do so hate it; a good dance somewhere is much more in my line".

'Fatty' was only twenty-one years of age when she began compiling her guide to running a Victorian home and she died just seven years later, by which date 2 million copies had been sold remaining in print ever since.

To view the entire text of The Book of Household Management click here and to read Chapter VII, The Natural History of Fishes and Chapter VIII, Fish Recipes click here.

The sources are listed in date order of publication

"The Forme of Cury" (1390) The Chief Master Cooks of King Richard II

"The Secret Library" (2016) Oliver Tearle at pages 51 & 52

We have Richard II to thank for several things. As well as providing Shakespeare with the subject for one of his finest early history plays, he is credited with introducing the handkerchief to England. He is also remembered for putting down the Peasants' Revolt while he was a boy of just fourteen.

But there is another thing for which we have Richard - in many ways a rather unpleasant king - to thank: the first cookbook written in English was compiled for him. The Forme of Cury ('The form of cooking') was put together by an anonymous author in around 1390. It contains nearly 200 recipes, including an early quiche (known then as a 'custard') and a 'blank mang', a sweet dish made with milk, rice, almonds, sugar and - er, slices of meat. It may not sound much but it was a popular dish at the time and would later evolve, for good or ill, into blancmange.

A number of ingredients - spices, in particular - feature in The Forme of Cury, making their debut in English records. Cloves and mace appear here for the first time in English cookery, and numerous other rare spices such as ginger, pepper and nutmeg are to be found in the recipes. Perhaps surprisingly - given that it is England's only native spice - mustard gets only one mention in the entire book, where it appears as 'mustard balls'.

| The Forme of Cury contains some of the first English recipes for three pasta dishes: ravioli, lasagne and macaroni cheese. |

The Forme of Cury is also the first English book to mention olive oil. An early salad recipe is listed: it includes parsley, sage, rosemary, garlic, mint, shallots, onions, fennel, and other herbs and vegetables, all shredded together in oil, vinegar and salt (indeed, the word salad derives from the Latin for 'salted').

Many of the recipes in The Forme of Cury haven't lasted. But the book did have one enduring legacy. That word 'cury', Middle English for 'cookery', would continue to be used by English traders travelling to the Far East, and would eventually be applied - at least according to one theory - to the spicy sauces used in Asian cooking. Which, so many language historians believe, is how we got the word 'curry'.

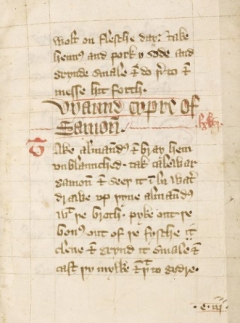

Editor's note: The Forme of Cury (The 'Method of Cooking', cury being from Middle French cuire: to cook) is an extensive collection of medieval English recipes from the 14th century. Originally in the form of a scroll, its authors are listed as "the chief Master Cooks of King Richard II". It is among the oldest English cookery books, and the first to mention olive oil, gourds, and spices such as mace and cloves.

'The Forme of Cury' contains the first known salmon recipe in an English cookbook - 'Viande Cypre of Samoun' translated as 'Salmon Meat Cyprus-style' - the ingredients of which comprise minced salmon with rice flour, sugar and spices:

VYANDE CYPRE OF SAMOUN [1] XX.IIII. XVIII.

Take Almandes and bray hem unblaunched. take calwar [2] Samoun and seeþ it in lewe water [3] drawe up þyn Almandes with the broth. pyke out the bones out of the fyssh clene & grynde it small & cast þy mylk & þat togyder & alye it with flour of Rys, do þerto powdour fort, sugur & salt & colour it with alkenet & loke þat hit be not stondyng and messe it forth.

[1] Samoun. Salmon.

[2] calwar. Salwar, No. 167. R. Holme says, "Calver is a term used to a Flounder when to be boiled in oil, vinegar, and spices and to be kept in it." But in Lancashire Salmon newly taken and immediately dressed is called Calver Salmon: and in Littleton Salar is a young salmon.

[3] lewe water. warm.

In the footnotes to these recipes compiled by Simon Pegge in 1780 he notes that "þ" ("thorn" and pronounced "th") being a "Saxon letter … is the ground of our present abbreviations ye the, y't that, y's this, &c. the y in these cases being evidently only an altered and more modern way of writing þ."

The other fish and fish-related recipes (48 in total) are as follows:

GYNGAWDRY [1]. XX.IIII.XIIII.

Take the Powche [2] and the Lyuour [3] of haddok, codlyng and hake [4] and of ooþer fisshe, parboile hem, take hem and dyce hem small, take of the self broth and wyne, a layour of brede of galyntyne with gode powdours and salt, cast þat fysshe þerinne and boile it. & do þerto amydoun. & colour it grene.

[1] Gyngawdry. Qu.

[2] Powche. Crop or stomach.

[3] Lyuour. Liver. V. No. 137.

[4] Hake. "Asellus alter, sive Merlucius, Aldrov." So Mr. Ray. See Pennant, III. p. 156.

GELE [1] OF FYSSH. C. I.

Take Tenches, pykes [2], eelys, turbut and plays [3], kerue hem to pecys. scalde hem & waische hem clene. drye hem with a cloth do hem in a panne do þerto half vyneger & half wyne & seeþ it wel. & take the Fysshe and pike it clene, cole the broth thurgh a cloth into a erthen panne. do þerto powdour of pep and safroun ynowh. lat it seeþ and skym it wel whan it is ysode dof [4] grees clene, cowche fisshes on chargeours & cole the sewe thorow a cloth onoward & serue it forth.

[1] Gele. Jelly. Gelee, Contents here and in the next Recipe. Gely, Ms. Ed. No. 55, which presents us with much the same prescription.

[2] It is commonly thought this fish was not extant in England till the reign of H. VIII.; but see No. 107. 109. 114. So Lucys, or Tenchis, Ms. Ed. II 1. 3. Pygus or Tenchis, II. 2. Pikys, 33 Chaucer, v. Luce; and Lel. Coll. IV. p. 226. VI. p. 1. 5. Luce salt. Ibid. p. 6. Mr. Topham's Ms. written about 1230, mentions Lupos aquaticos five Luceas amongst the fish which the fishmonger was to have in his shop. They were the arms of the Lucy family so early as Edw. I. See also Pennant's Zool. III. p. 280, 410.

[3] Plays. Plaise, the fish.

[4] Dof, i. e. do of.

CHYSANNE [1]. C. III.

Take Roches. hole Tenches and plays & sinyte hem to gobettes. fry hem in oyle blaunche almaundes. fry hem & cast wyne & of vyneger þer pridde part þ erwith fyges drawen & do þerto powdour fort and salt. boile it. lay the Fisshe in an erthen panne cast the sewe þerto. seeþ oynouns ymynced & cast þerinne. kepe hit and ete it colde.

[1] Chysanne. Qu.

CONGUR [1] IN SAWSE. C. IIII.

Take the Conger and scald hym. and smyte hym in pecys & seeþ hym. take parsel. mynt. peleter. rosmarye. & a litul sawge. brede and salt, powdour fort and a litel garlec, clower a lite, take and grynd it wel, drawe it up with vyneger thurgh a clot. cast the fyssh in a vessel and do þe sewe onoward & serue it forth.

[1] Congur. The Eel called Congre. Sawce, Contents here, and No. 105, 106.

RYGH [1] IN SAWSE. C. V.

Take Ryghzes and make hem clene and do hem to seeþ, pyke hem clene and frye hem in oile. take Almandes and grynde hem in water or wyne, do þerto almandes blaunched hole fryed in oile. & coraunce seeþ the lyour grynde it smale & do þerto garlec ygronde & litel salt & verious powdour fort & safroun & boile it yfere, lay the Fysshe in a vessel and cast the sewe þerto. and messe it forth colde.

[1] Rygh. A Fish, and probably the Ruffe.

MAKEREL IN SAWSE. C. VI.

Take Makerels and smyte hem on pecys. cast hem on water and various. seeþ hem with mynter and wiþ oother erbes, colour it grene or zelow, and messe it forth.

PYKES IN BRASEY [1]. C. VII.

Take Pykes and undo hem on þe wombes [2] and waisshe hem clene and lay hem on a roost Irne [3] þenne take gode wyne and powdour gynger & sugur good wone [4] & salt, and boile it in an erthen panne & messe forth þe pyke & lay the sewe onoward.

[1] Brasey. Qu.

[2] Wombs. bellies.

[3] roost Irene. a roasting iron.

[4] good wone. a good deal. V. Gloss.

PORPEYS IN BROTH. C. VIII.

Make as þou madest Noumbles of Flesh with oynouns.

BALLOC [1] BROTH. C. IX.

Take Eelys and hilde [2] hem and kerue hem to pecys and do hem to seeþ in water and wyne so þat it be a litel ouer stepid [3]. do þerto sawge and ooþer erbis with few [4] oynouns ymynced, whan the Eelis buth soden ynowz do hem in a vessel, take a pyke and kerue it to gobettes and seeþ hym in the same broth do þerto powdour gynger galyngale canel and peper, salt it and cast the Eelys þerto & messe it forth.

[1] Balloc. Ballok, Contents.

[2] hilde. skin.

[3] on stepid. steeped therein. V. No. 110.

[4] few, i.e. a few.

ELES IN BREWET. C. X.

Take Crustes of brede and wyne and make a lyour, do þerto oynouns ymynced, powdour. & canel. & a litel water and wyne. loke þat it be stepid, do þerto salt, kerue þin Eelis & seeþ hem wel and serue hem forth.

CAWDEL OF SAMOUN C.XI.

Take the guttes of Samoun and make hem clene. perboile hem a lytell. take hem up and dyce hem. slyt the white of Lekes and kerue hem smale. cole the broth and do the lekes þerinne with oile and lat it boile togyd yfere [1]. do the Samoun icorne þerin, make a lyour of Almaundes mylke & of brede & cast þerto spices, safroun and salt, seeþ it wel. and loke þat it be not stondyng.

[1] togyd yfere. One of these should be struck out.

PLAYS IN CYEE. C.XII.

Take Plays and smyte hem [1] to pecys and fry hem in oyle. drawe a lyour of brede & gode broth & vyneger. and do þerto powdour gynger. canel. peper and salt and loke þat it be not stondyng.

[1] Vide No. 104. Qu.

FOR TO MAKE NOUMBLES IN LENT. C. XIIII.

Take the blode of pykes oþer of conger and nyme [1] the paunches of pykes. of conger and of grete code lyng [2], & boile hem tendre & mynce hem smale & do hem in þat blode. take crustes of white brede & strayne it thurgh a cloth. þenne take oynouns iboiled and mynced. take peper and safroun. wyne. vynegur aysell [3] oþer alegur & do þerto & serue forth.

[1] nyme. take. Perpetually used in Ms. Ed. from Sax. niman.

[2] code lyng. If a Codling be a small cod, as we now understand it, great codling seems a contradiction in terms.

[3] Aysell. Eisel, vinegar. Littleton.

FOR TO MAKE CHAWDON [1] FOR LENT. C. XV.

Take blode of gurnardes and congur & þe paunch of gurnardes and boile hem tendre & mynce hem smale, and make a lyre of white Crustes and oynouns ymynced, bray it in a morter & þanne boile it togyder til it be stondyng. þenne take vynegur oþ aysell & safroun & put it þerto and serue it forth.

[1] Chawdoun. V. Gloss.

FURMENTE WITH PORPEYS. C. XVI.

Take clene whete and bete it small in a morter and fanne out clene the doust, þenne waisthe it clene and boile it tyl it be tendre and broun. þanne take the secunde mylk of Almaundes & do þerto. boile hem togidur til it be stondyng, and take þe first mylke & alye it up wiþ a penne [1]. take up the porpays out of the Furmente & leshe hem in a dishe with hoot water. & do safroun to þe furmente. and if the porpays be salt. seeþ it by hym self, and serue it forth.

[1] Penne. Feather, or pin. Ms. Ed. 28.

TENCHES IN CYNEE. XX.VI.

Take Tenches and smyte hem to pecys, fry hem, drawe a lyour of Raysouns coraunce witþ wyne and water, do þerto hool raisouns & powdour of gyngur of clowes of canel of peper do the Tenches þerto & seeþ hem with sugur cypre & salt. & messe forth.

OYSTERS IN GRAVEY. XX.VI. I.

Schyl [1] Oysters and seeþ hem in wyne and in hare [2] own broth. cole the broth thurgh a cloth. take almandes blaunched, grynde hem and drawe hem up with the self broth. & alye it wiþ flour of Rys. and do the oysters þerinne, cast in powdour of gyngur, sugur, macys. seeþ it not to stondyng and serue forth.

[1] shell, take of the shells.

[2] hare. their. her. No. 123. Chaucer.

MUSKELS [1] IN BREWET. XX.VI. II.

Take muskels, pyke hem, seeþ hem with the owne broth, make a lyour of crustes [2] & vynegur do in oynouns mynced. & cast the muskels þerto & seeþ it. & do þerto powdour with a lytel salt & safron the samewise make of oysters.

[1] Muskles. muskels below, and the Contents. Muscles.

[2] crustes. i.e. of bread.

OYSTERS IN CYNEE. XX.VI. III.

Take Oysters parboile hem in her owne broth, make a lyour of crustes of brede & drawe it up wiþ the broth and vynegur mynce oynouns & do þerto with erbes. & cast the oysters þerinne. boile it. & do þerto powdour fort & salt. & messe it forth.

CAWDEL OF MUSKELS. XX.VI. IIII.

Take and seeþ muskels, pyke hem clene, and waisshe hem clene in wyne. take almandes & bray hem. take somme of the muskels and grynde hem. & some hewe smale, drawe the muskels yground with the self broth. wryng the almaundes with faire water. do alle þise togider. do þerto verious and vyneger. take whyte of lekes & parboile hem wel. wryng oute the water and hewe hem smale. cast oile þerto with oynouns parboiled & mynced smale do þerto powdour fort, safroun and salt. a lytel seeþ it not to to [1] stondyng & messe it forth.

[1] to to, i. e. too too. Vide No. 17.

MORTREWS OF FYSSH. XX.VI. V.

Take codlyng, haddok, oþ hake and lynours with the rawnes [1] and seeþ it wel in water. pyke out þe bones, grynde smale the Fysshe, drawe a lyour of almaundes & brede with the self broth. and do the Fysshe grounden þerto. and seeþ it and do þerto powdour fort, safroun and salt, and make it stondyng.

[1] rawnes. roes.

LAUMPREYS IN GALYNTYNE. XX.VI. VI.

Take Laumpreys and sle [1] hem with vynegur oþer with white wyne & salt, scalde hem in water. slyt hem a litel at þer nauel…. & rest a litel at the nauel. take out the guttes at the ende. kepe wele the blode. put the Laumprey on a spyt. roost hym & kepe wel the grece. grynde raysouns of coraunce. hym up [2] with vyneger. wyne. and crustes of brede. do þerto powdour of gyngur. of galyngale [3]. flour of canel. powdour of clowes, and do þerto raisouns of coraunce hoole. with þe blode & þe grece. seeþ it & salt it, boile it not to stondyng, take up the Laumprey do hym in a chargeour [4], & lay þe sewe onoward, & serue hym forth.

[1] sle. slay, kill.

[2] hym up. A word seems omitted; drawe or lye.

[3] of galyngale, i. e. powder. V. No. 101.

[4] Chargeour. charger or dish. V. No. 127.

LAUMPROUNS IN GALYNTYNE. XX.VI. VII.

Take Lamprouns and scalde hem. seeþ hem, meng powdour galyngale and some of the broth togyder & boile it & do þerto powdour of gyngur & salt. take the Laumprouns & boile hem & lay hem in dysshes. & lay the sewe above. & serue fort.

LOSEYNS [1] IN FYSSH DAY. XX.VI. VIII.

Take Almandes unblaunched and waisthe hem clene, drawe hem up with water. seeþ þe mylke & alye it up with loseyns. cast þerto safroun. sugur. & salt & messe it forth with colyandre in confyt rede, & serue it forth.

[1] Loseyns. Losyns, Contents.

SOBRE SAWSE. XX.VI. X.

Take Raysouns, grynde hem with crustes of brede; and drawe it up with wyne. do þerto gode powdours and salt. and seeþ it. fry roches, looches, sool, oþer ooþer gode Fyssh, cast þe sewe above, & serue it forth.

EGURDOUCE [1] OF FYSSHE. XX.VI.XIII.

Take Loches oþer Tenches oþer Solys smyte hem on pecys. fry hem in oyle. take half wyne half vynegur and sugur & make a siryp. do þerto oynouns icorue [2] raisouns coraunce. and grete raysouns. do þerto hole spices. gode powdours and salt. messe þe fyssh & lay þe sewe aboue and serue forth.

[1] Egurdouce. Vide Gloss.

[2] icorue, icorven. cut. V. Gloss.

CRUSTARDES OF FYSSHE. XX.VII. XVI.

Take loches, laumprouns, and Eelis. smyte hem on pecys, and stewe hem wiþ Almaund Mylke and verions, frye the loches in oile as tofore. and lay þe fissh þerinne. cast þeron powdour fort powdour douce. with raysons coraunce & prunes damysyns. take galyntyn and þe sewe þerinne, and swyng it togyder and cast in the trape. & bake it and serue it forth.

CRUSTARDES OF EERBIS [1] ON FYSSH DAY. XX.VII. XVII.

Take gode Eerbys and grynde hem smale with wallenotes pyked clene. a grete portioun. lye it up almost wiþ as myche verions as water. seeþ it wel with powdour and Safroun withoute Salt. make a crust in a trape and do þe fyssh þerinne unstewed wiþ a litel oile & gode Powdour. whan it is half ybake do þe sewe þerto & bake it up. If þou wilt make it clere of Fyssh seeþ ayrenn harde. & take out þe zolkes & grinde hem with gode powdours. and alye it up with gode stewes [2] and serue it forth.

[1] Erbis. Rather Erbis and Fissh.

[2] stewes. V. No. 170.

TART DE BRYMLENT [1]. XX.VIII. VII.

Take Fyges & Raysouns. & waisshe hem in Wyne. and grinde hem smale with apples & peres clene ypiked. take hem up and cast hem in a pot wiþ wyne and sugur. take salwar Salmoun [2] ysode. oþer codlyng, oþer haddok, & bray hem smal. & do þerto white powdours & hool spices. & salt. and seeþ it. and whanne it is sode ynowz. take it up and do it in a vessel and lat it kele. make a Coffyn an ynche depe & do þe fars þerin. Plaunt it boue [3] with prunes and damysyns. take þe stones out, and wiþ dates quarte rede [4] dand piked clene. and couere the coffyn, and bake it wel, and serue it forth.

[1] Brymlent. Perhaps Midlent or High Lent. Bryme, in Cotgrave, is the midst of Winter. The fare is certainly lenten. A.S. [Anglo-Saxon: bryme]. Solennis, or beginning of Lent, from A.S. [Anglo-Saxon: brymm], ora, margo. Yet, after all, it may be a mistake for Prymlent.

[2] salwar Samoun. V. ad No. 98.

[3] plaunt it above. Stick it above, or on the top.

[4] quarte red. quartered.

TARTES OF FYSSHE. XX.VIII. X.

Take Eelys and Samoun and smyte hem on pecys. & stewe it [1] in almaund mylke and verious. drawe up on almaund mylk wiþ þe stewe. Pyke out the bones clene of þe fyssh. and save þe myddell pece hoole of þe Eelys & grinde þat ooþer fissh smale. and do þerto powdour, sugur, & salt and grated brede. & fors þe Eelys þerwith þerer as [2] þe bonys were medle þe ooþer dele of the fars & þe mylk togider. and colour it with saundres. make a crust in a trape as before. and bake it þerin and serue it forth.

[1] it. rather hem, i.e. them.

[2] þereras. where. V. No. 177.

CHEWETES ON FYSSH DAY. XX.IX.VI.

Take Turbut. haddok. Codlyng. and hake. and seeþ it. grynde it smale. and do þerto Dates. ygrounden. raysouns pynes. gode powdoer and salt. make a Coffyn as tofore saide. close þis þerin. and frye it in oile. oþer stue it in gyngur. sugur. oþer in wyne. oþer bake it. & serue forth.

Appendix

I. FOR TO MAKE EGARDUSE [1].

Tak Lucys [2] or Tenchis and hak hem smal in gobette and fry hem in oyle de olive and syth nym vineger and the thredde party of sugur and myncyd onyons smal and boyle al togedere and cast thereyn clowys macys and quibibz and serve yt forthe.

[1] See No. 21 below, and part I. No. 50.

[2] Lucy, I presume, means the Pike; so that this fish was known here long before the reign of H. VIII. though it is commonly thought otherwise. V. Gloss.

II. FOR TO MAKE RAPY [1].

Tak pyg' or Tenchis or other maner fresch fysch and fry yt wyth oyle de olive and syth nym the crustys of wyt bred and canel and bray yt al wel in a mortere and temper yt up wyth god wyn and cole [2] yt thorw an hersyve and that yt be al cole [3] of canel and boyle yt and cast therein hole clowys and macys and quibibz and do the fysch in dischis and rape [4] abovyn and dresse yt forthe.

[1] Vide No. 49.

[2] Strain, from Lat. colo.

[3] Strained, or cleared.

[4] This Rape is what the dish takes its name from. Perhaps means grape from the French raper. Vide No. 28.

III. FOR TO MAKE FYGEY.

Nym Lucys or tenchis and hak hem in morsell' and fry hem tak vyneger and the thredde party of sugur myncy onyons smal and boyle al togedyr cast ther'yn macis clowys quibibz and serve yt forth.

VII. FOR TO MAKE BLOMANGER [1] OF FYSCH.

Tak a pound of rys les hem wel and wasch and seth tyl they breste and lat hem kele and do ther'to mylk of to pound of Almandys nym the Perche or the Lopuster and boyle yt and kest sugur and salt also ther'to and serve yt forth.

[1] See note on No. 14. of Part I.

IX. FOR TO MAKE LAMPREY FRESCH IN GALENTYNE [1].

Schal be latyn blod atte Navel and schald yt and rost yt and ley yt al hole up on a Plater and zyf hym forth wyth Galentyn that be mad of Galyngale gyngener and canel and dresse yt forth.

[1] This is a made or compounded thing. See both here, and in the next Number, and v. Gloss.

X. FOR TO MAKE SALT LAMPREY IN GALENTYNE [1].

Yt schal be stoppit [2] over nyzt in lews water and in braan and flowe and sodyn and pyl onyons and seth hem and ley hem al hol by the Lomprey and zif hem forthe wyth galentyne makyth [3] wyth strong vyneger and wyth paryng of wyt bred and boyle it al togeder' and serve yt forthe.

[1] See note [1] on the last Number.

[2] Perhaps, steppit, i.e. steeped. See No. 12.

[3] Perhaps, makyd, i.e. made.

XI. FOR TO MAKE LAMPREYS IN BRUET.

They schulle be schaldyd and ysode and ybrulyd upon a gredern and grynd peper and safroun and do ther'to and boyle it and do the Lomprey ther'yn and serve yt forth.

XIII. FOR TO MAKE SOLYS IN BRUET.

They schal be fleyn and sodyn and rostyd upon a gredern and grynd Peper and Safroun and ale boyle it wel and do the sole in a plater and the bruet above serve it forth.

XIV. FOR TO MAKE OYSTRYN IN BRUET.

They schul be schallyd [1] and ysod in clene water grynd peper safroun bred and ale and temper it wyth Broth do the Oystryn ther'ynne and boyle it and salt it and serve it forth.

[1] Have shells taken off.

XV. FOR TO MAKE ELYS IN BRUET.

They schul be flayn and ket in gobett' and sodyn and grynd peper and safroun other myntys and persele and bred and ale and temper it wyth the broth and boyle it and serve it forth.

XVI. FOR TO MAKE A LOPISTER.

He schal be rostyd in his scalys in a ovyn other by the Feer under a panne and etyn wyth Veneger.

XXV. FOR TO MAKE TARTYS OF FYSCH OWT OF LENTE.

Mak the Cowche of fat chese and gyngener and Canel and pur' crym of mylk of a Kow and of Helys ysodyn and grynd hem wel wyth Safroun and mak the chowche of Canel and of Clowys and of Rys and of gode Spycys as other Tartys fallyth to be.

XXVIII. FOR TO MAKE RAPEE [1].

Tak the Crustys of wyt bred and reysons and bray hem wel in a morter and after temper hem up wyth wyn and wryng hem thorw a cloth and do ther'to Canel that yt be al colouryt of canel and do ther'to hole clowys macys and quibibz the fysch schal be Lucys other Tenchis fryid or other maner Fysch so that yt be fresch and wel yfryed and do yt in Dischis and that rape up on and serve yt forth.

[1] Vide Part I. No. 49.

XXVIII. FOR TO MAKE RAPEE [1].

Tak the Crustys of wyt bred and reysons and bray hem wel in a morter and after temper hem up wyth wyn and wryng hem thorw a cloth and do ther'to Canel that yt be al colouryt of canel and do ther'to hole clowys macys and quibibz the fysch schal be Lucys other Tenchis fryid or other maner Fysch so that yt be fresch and wel yfryed and do yt in Dischis and that rape up on and serve yt forth.

[1] Vide Part I. No. 49.

XXX. FOR TO MAKE FORMENTY ON A FICHSSDAY [1].

Tak the mylk of the Hasel Notis boyl the wete [2] wyth the aftermelk til it be dryyd and tak and coloured [3] yt wyth Safroun and the ferst mylk cast ther'to and boyle wel and serve yt forth.

[1] Fishday.

[2] white.

[3] Perhaps, colour.

XXXIII. FOR TO MAKE A BALOURGLY [1] BROTH.

Tak Pikys and spred hem abord and Helys zif thou hast fle hem and ket hem in gobettys and seth hem in alf wyn [2] and half in water. Tak up the Pykys and Elys and hold hem hote and draw the Broth thorwe a Clothe do Powder of Gyngener Peper and Galyngale and Canel into the Broth and boyle yt and do yt on the Pykys and on the Elys and serve yt forth.

[1] This is so uncertain in the original, that I can only guess at it.

[2] Perhaps, alf in wyn, or dele in before water.

"A Book of Cookrye very necessary for all such as delight therin" (1591) A. W.

And now newlye enlarged with the serving in of the Table

With the proper Sauces to each of them convenient

At London

Printed by Edward Allde. 1591

(originally published 1584)

Click here to read the text online.

A Pudding in a Tench

Take your Tench and drawe it very cleane, and cut it not overlowe. Then take beets boiled, or Spinage, and choppe it with yolks of hard Egges, Corance, grated Bread, salt, Pepper, Sugar and Sinamon, and yolks of raw Egges, and mingle it togither, and put it in the Tenches bellye, then put it in a platter with faire water and sweet butter, and turn it in the Platter, and set it in the Oven, and when it is inough, serve it in with sippits and poure the licour that it was boiled in upon it.

For Fish

To seethe a Pike

Scoure your Pike with bay Salte, and then open him on the back, faire washe him, and then cast a little white Salte upon him. Set on faire water wel seasoned with Salte. When this licoour seetheth, then put in your Pike and fair scum it, then take the best of the broth when it is sodden, and put it in a little Chafer or Pipkin, and put therto parcely and a little Time, Rosemary, whole Mace, good Yest, and half as much Vergious as you have licour, and boile them togither, and put in the Liver of the Pike, and the kell, being clean scaled and washed, and let them boyle well, then season your broth with pepper groce beaten, with salt not too much, because your licour is Salte that your Pike is boyled in, put therein a good peece of sweete Butter, and season it with a little Sugar that it be neither tooo sharpen nor too sweet. So take up your pike and laye it upon Sops the skinny side upward, and so lay your broth upon it.

A Pike sauce for a Pike, Bream, Perch, roch, Carp, Flounders, and all manner of Brooke fish

Take a posie of Rosemary and Time, and binde them together, and put in also a quantity of Parcelye not bound, and put it into a Cauldron of water, salte, and Yest, and the hearbes, and let them boyle a prettie while, then put in the Fishe, and a good quantitie of Butter, and let them boyle a good while, and you shall have your Pyke Sauce. For all these Fishes above written if they must be broyled: take sauce for them, Butter, Pepper and Vinagre, and boyle it upon a chafing dish, and then lay the broyled fish upon the dish, but for Eeles and fresh Salmon nothing but pepper and Vinagre over-boyled, and also if you will frye them, you must take a good quantity of Percely, after the Fish is fryed, put in the percelye into the Frying pan, and let it frye in the butter, then take it up and put it on the fryed Fish, as fryed Plaice, Whiting, and such other fish, except Eeles, fresh Salmon and Cunger, which be never fried, but baked, broiled, roasted and sodden.

How to seeth a Carpe

Cut the throat of your Carp, & save the blood in a saucer, and take your Carpe and scoure him with Salt, take out the gal and the Guts, and leave the Liver and the fat in the belly of the Carp, set on your licour, water and Salt to seeth him, and when your licour seethes, put in your carp or ever he be dead, and take good heede for springing out of the Pan, for it is ever good to seethe fish quick, for it maketh the fish to eat hard. Take the best of the broth and a little red Wine, good store of Vergious, new yest, with the blood of the Carp strained, and so put it in a Pipkin with Corance, whole Pepper, and boyle them altogither, put therto half a dish of sweet butter, and a little time, and Barberies if you have them, and when they be well boyled, season it not too sweet nor too sharpe, and then poure it upon your Carpe.

To seeth Roches, Flounders, or Eeles

Make ye good broth with new yest, put therin vergious, salt, percely, a little Time, and not much rosemary and pepper, so set it upon the fire and boile it, and when it is well boyled put in the Roches, Flounders, Eeles and a little sweet butter.

To seeth a Gurnard

Open your Gurnard in the back, and faire wash and seeth it in water & Salt, with the fishy side upward, and when it is well sod, take some of the best of the broth if you will, or els a little fair water, and put to it new yest, a little vergious, percely, rosemary, a little time, a peece of sweet butter, and whole Mace, and let it boyle in a pipkin by it self till it be well boyled, and then when you serve in your Gurnard, poure the same broth upon it.

To seeth a Dory or Mullet

Make your broth light with yest, somewhat savery with salt, and put therin a little Rosemary, and when it seethes put in your fish and let it seeth very softly, take faire water and vergious a like much, and put therto a little new Yest, corance, whole pepper and a little Mace, and Dates shred very fine, and boyle them wel togither, and when they be well boyled, take the best of your broth that your fish is sodden in, and put to it strawberyes, gooseberyes, or barberyes, sweet Butter, some Sugar, and so season up your broth, and poure upon your Dorry or Mullet.

To seeth Turbut or Cunger

Set on water and salt, and season it wel, if the Turbut be great quarter him into foure quarters, if he be small, cut him but in halfe, if it be a Burt, seethe it whole after this sort. When your licour doth seeth, put in your fish and let it seeth very softly till it be sodden enough, and when it is sodden, take it not up till the licour be colde. Then take halfe white Wine, with Vinagre and the broth that it was sodden in, and lay the fish in it to souce, Cungar, Sturgion, and all Fish that is to be souced, in like manner saving you must seethe your Sturgion in water and Salte, and souce it with white Wine.

How to seeth Shrimps

Take halfe water and halfe beere or Ale, and some salt good and savery, and set it on the fire and faire scum it, and when it seetheth a full wallop, put in your Shrimpes faire washed, and seethe them with a quick fire, scum them very clean, and let them have but two walmes, then take them up with a scummer, and lay them upon a fair white cloth, and sprinkle a little white salt upon them.

To make Florentines with Eeles for Fish dayes

Take great Eeles, fleye them and perboyle them a little, then take the fishe from the bones, and mince it small with some Wardens amongst it to make it to mince small, and season it with cloves and mace, pepper, Corance and Dates, and when you lay it into your paste, take a little fine Sugar and lay it upon before you cover it, and when it is halfe baked or altogither, laye a peece of sweet Butter upon cover, and a little rosewater and sugar. After the same manner, minced pyes of Eeles.

How to bake Eeles whole

When they be fleyed & clean washed, season them with vergious, pepper, and salt, Cloves and mace, and put to them corance, great Raisins and Prunes, sweete butter and Vergious.

To bake Lamprons

Faire scoure them or fleye them, and season them with pepper and Salt, and put to them some onions, vergious, butter and Oisters.

How to bake Lamprons fine

Put to them small Raisins and Onyons minced very fine, and dates minced fine, a little whole Mace, some Prunes, if you will butter and vergious.

How to bake a Lamprey

When you have fleied and washed it clean, season it with Pepper, and salt, and make a light Gallandine and put to it good store of butter, and after this sort you must make your gallandine. Take white bread tostes and lay them in steep in Claret wine, or else in vergious, & so strain them with vinagre, and make it somewhat thin, and put sugar, Sinamon and ginger, and boyle it on a Chafing dish of coles, this Galandine being not too thicke, put it into your pye of Lampreye, and after this sort shall you bake Porpos or Puffins.

To bake Carp, Bream, Mullet, Pike, Trout, Roche or any other kinde of Fish

Season them with Cloves and Mace, and pepper, and bake them with smal raisins, sweete butter and Vergious, great raisins, and some prunes.

How to bake a Holybut head

First water it till it be fresh then cut it in small peeces like Culpines of an Eele, and season it with pepper & Saffron, cloves and mace, small raisins & great, and meddle al these wel togither, and also put therto a good messe of vergious, and so bake the same Fish.

How to bake Cunger

Season it with pepper and salt and make your pies but even meet for one gubbin, and put to it sweet butter, & let it not drye.

To bake a Stockfish

Season your Stockfish with pepper & salt and lay it into the paste, and put good store of butter to it, and shred onions small, and percely, and cast it upon the stockfish, & put a little vergious unto it, and bake it.

How to bake watered Herrings

Let your Herrings be wel watered, and season them with Pepper and a little Cloves and mace, and put unto them minced Onions, great raisins and small, a little sweet butter, and a little sugar, and so bake them.

To make Allowes of Eeles

Take and splat an Eele by the back, and keepe the belly whole, and so take out the bone, then take onions, percely, Time, and Rosemary chopped together, and put therto pepper and salt, and a little Saffron, and so lay it upon the Eeles, and then wrap it up in Culpines, and put them upon a spit and so roast them.

To make a Fricase of a good Haddock or Whiting

First seeth the fish and scum it, and pick out the bones, take Onions and chop them small then fry them in Butter or Oyle till they be enough, and put in your Fish, and frye them till it be drye, that doon: serve it forth with pouder of Ginger on it.

To fry Whitings

First flay them and wash them clean and scale them, that doon, lap them in floure and fry them in Butter and oyle. Then to serve them, mince apples or onions and fry them, then put them into a vessel with white wine, vergious, salt, pepper, cloves & mace, and boile them togither on the Coles, and serve it upon the Whitings.

To fry a Codshead

First cleve it in peeces and washe it clean and fry it in Butter or Oyle. Then cut Onions in rundels and so frye them, that doon put them in a vessell, and put to them red wine or vinagre, salt, ginger, sinamon, cloves & mace, and boile all these well togither, and then serve it upon your cods head.

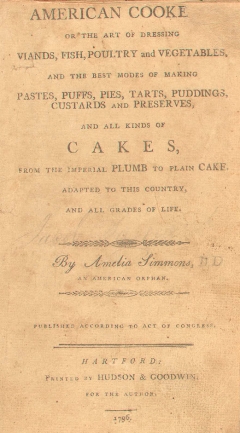

"American Cookery: or the art of dressing viands, fish, poultry and vegetables, and the best modes of making pastes, puffs, pies, tarts, puddings, custards and preserves, and all kinds of cakes, from the imperial plumb to plain cake. Adapted to this country, and all grades of life" (1796) Amelia Simmons

Click here to read online

Preface

As this treatise is calculated for the improvement of the rising generation of females in America, the lady of fashion and fortune will not be displeased, if many hints are suggested for the more general and universal knowledge of those females in this country, who by the loss of their parents, or other unfortunate circumstances, are reduced to the necessity of going into families in the line of domestics, or taking refuge with their friends or relations, and doing those things which are really essential to the perfecting them as good wives, and useful members of society. The orphan, tho' left to the care of virtuous guardians, will find it essentially necessary to have an opinion and determination of her own. The world, and the fashion thereof, is so variable, that old people cannot accommodate themselves to the various changes and fashions which daily occur; they will adhere to the fashion of their day, and will not surrender their attachments to the good old way while the young and the gay, bend and conform readily to the taste of the times, and fancy of the hour.

By having an opinion and determination, I would not be understood to mean an obstinate perseverance in trifles, which borders on obstinacy - by no means, but only an adherence to those rules and maxims which have flood the test of ages, and will forever establish the "female character", a virtuous character - altho' they conform to the ruling taste of the age in cookery, dress, language, manners, &c.

It must ever remain a check upon the poor solitary orphan, that while those females who have parents, or brothers, or riches, to defend their indiscretions, that the orphan must depend solely upon "character". How immensely important, therefore, that every action, every word, every thought, be regulated by the strictest purity, and that every movement meet the approbation of the good and wise.

The candour of the American Ladies is solicitously intreated by the Authoress, as she is circumscribed in her knowledge, this being an original work in this country. Should any future editions appear, she hopes to render it more valuable.

Directions for catering, or the procuring the best viands, fish, &c.

…

Fish, how to choose the best in market

Salmon, the noblest and richest fish taken in fresh water - the largest are the best. They are unlike almost every other fish, are ameliorated by being 3 or 4 days out of water, if kept from heat and the moon, which has much more injurious effect than the sun.

In all great fish-markets, great fish-mongers strictly examine the gills - if the bright redness is exchanged for a low brown, they are stale; but when live fish are brought flouncing into market, you have only to elect the kind most agreeable to your palate and the season.

Shad, contrary to the generally received opinion are not so much richer flavoured, as they are harder when first taken out of the water; opinions vary respecting them. I have tasted Shad thirty or forty miles from the place where caught, and really conceived that they had a richness of flavour, which did not appertain to those taken fresh and cooked immediately, and have proved both at the same table, and the truth may rest here, that a Shad 36 or 48 hours out of water, may not cook so hard and solid, and be esteemed so elegant, yet give a higher relished flavour to the taste.

Every species generally of salt water fish are best fresh from the water, tho' the Hannah Hill, Black Fish, Lobster, Oyster, Flounder, Bass, Cod, Haddock, and Eel, with many others, may be transported by land many miles, find a good market, and retain a good relish; but as generally, live ones are bought first, deceits are used to give them a freshness of appearance, such as peppering the gills, wetting the fins and tails, and even painting the gills, or wetting with animal blood. Experience and attention will dictate the choice of the best. Fresh gills, full bright eyes, moist fins and tails, are denotements of their being fresh caught; if they are soft, its certain they are stale, but if deceits are used, your smell must approve or denounce them, and be your safest guide.

Of all fresh water fish, there are none that require, or so well afford haste in cookery, as the Salmon Trout, they are best when caught under a fall or cateract - from what philosophical circumstance is yet unsettled, yet true it is, that at the foot of a fall the waters are much colder than at the head; Trout choose those waters; if taken from them and hurried into dress, they are genuinely good; and take rank in point of superiority of flavour, of most other fish.

Perch and Roach, are noble pan fish, the deeper the water from whence taken, the finer are their flavours; if taken from shallow water, with muddy bottoms, they are impregnated therewith, and are unsavoury.

Eels, though taken from muddy bottoms, are best to jump in the pan.

Most white or soft fish are best bloated, which is done by salting, peppering, and drying in the sun, and in a chimney; after 30 or 40 hours drying, are best broiled, and moistened with butter, &c.

…

For dressing Codfish

Put the fish first into cold water and wash it, then hang it over the fire and soak it six hours in scalding water, then shift it into clean warm water, and let it scald for one hour, it will be much better than to boil.

…

"The American Frugal Housewife: dedicated to those who are not ashamed of economy" (1832) Lydia Maria Child at sections 58, 59, 60, 84 & 121

Click here to read online

Introductory chapter

The true economy of housekeeping is simply the art of gathering up all the fragments, so that nothing be lost. I mean fragments of time, as well as materials. Nothing should be thrown away so long as it is possible to make any use of it, however trifling that use may be; and whatever be the size of a family, every member should be employed either in earning or saving money …

… The sooner children are taught to turn their faculties to some account, the better for them and for their parents …

In this country, we are apt to let children romp away their existence, till they get to be thirteen or fourteen. This is not well. It is not well for the purses and patience of parents; and it has a still worse effect on the morals and habits of the children. Begin early is the great maxim for everything in education. A child of six years old can be made useful; and should be taught to consider every day lost in which some little thing has not been done to assist others.

Children can very early be taught to take all the care of their own clothes.

They can knit garters, suspenders, and stockings; they can make patchwork and braid straw; they can make mats for the table, and mats for the floor; they can weed the garden, and pick cranberries from the meadow, to be carried to market.

Provided brothers and sisters go together, and are not allowed to go with bad children, it is a great deal better for the boys and girls on a farm to be picking blackberries at six cents a quart, than to be wearing out their clothes in useless play. They enjoy themselves just as well; and they are earning something to buy clothes, at the same time they are tearing them …

Fish

58

Cod has white stripes, and a haddock black stripes; they may be known apart by this. Haddock is the best for frying; and cod is the best for boiling, or for a chowder. A thin tail is a sign of a poor fish; always choose a thick fish. When you are buying mackerel, pinch the belly to ascertain whether it is good. If it gives under your finger, like a bladder half filled with wind, the fish is poor; if it feels hard like butter, the fish is good. It is cheaper to buy one large mackerel for nine pence, than two for four pence half-penny each.

Fish should not be put in to fry until the fat is boiling hot; it is very necessary to observe this. It should be dipped in Indian meal before it is put in; and the skinny side uppermost, when first put in, to prevent its breaking. It relishes better to be fried after salt pork, than to be fried in lard alone. People are mistaken, who think fresh fish should be put into cold water as soon as it is brought into the house; soaking it in water is injurious. If you want to keep it sweet, clean it, wash it, wipe it dry with a clean towel, sprinkle salt inside and out, put it in a covered dish, and keep it on the cellar floor until you want to cook it. If you live remote from the seaport, and cannot get fish while hard and fresh, wet it with an egg beaten, before you meal it, to prevent its breaking.

Fish gravy is very much improved by taking out some of the fat, after the fish is fried, and putting in a little butter. The fat thus taken out will do to fry fish again; but it will not do for any kind of shortening. Shake in a little flour into the hot fat, and pour in a little boiling water; stir it up well, as it boils, a minute or so. Some people put in vinegar; but this is easily added by those who like it.

A common sized cod-fish should be put in when the water is boiling hot, and boil about twenty minutes. Haddock is not as good for boiling as cod; it takes about the same time to boil.

A piece of halibut which weighs four pounds is a large dinner for a family of six or seven. It should boil forty minutes. No fish put in till the water boils. Melted butter for sauce.

59

Clams should boil about fifteen minutes in their own water; no other need be added, except a spoonful to keep the bottom shells from burning. It is easy to tell when they are done, by the shells starting wide open. After they are done, they should be taken from the shells, washed thoroughly in their own water, and put in a stewing pan. The water should then be strained through a cloth, so as to get out all the grit; the clams should be simmered in it ten or fifteen minutes; a little thickening of flour and water added; half a dozen slices of toasted bread or cracker; and pepper, vinegar and butter to your taste. Salt is not needed.

Four pounds of fish are enough to make a chowder for four or five people; half a dozen slices of salt pork in the bottom of the pot; hang it high, so that the pork may not burn; take it out when done very brown; put in a layer of fish, cut in lengthwise slices, then a layer formed of crackers, small or sliced onions, and potatoes sliced as thin as a four-pence, mixed with pieces of pork you have fried; then a layer of fish again, and so on. Six crackers are enough. Strew a little salt and pepper over each layer; over the whole pour a bowl-full of flour and water, enough to come up even with the surface of what you have in the pot. A sliced lemon adds to the flavour. A cup of tomato catsup is very excellent. Some people put in a cup of beer. A few clams are a pleasant addition. It should be covered so as not to let a particle of steam escape, if possible. Do not open it, except when nearly done, to taste if it be well seasoned.

Salt fish should be put in a deep plate, with just water enough to cover it, the night before you intend to cook it. It should not be boiled an instant; boiling renders it hard. It should lie in scalding hot water two or three hours. The less water is used, and the more fish is cooked at once, the better. Water thickened with flour and water while boiling, with sweet butter put in to melt, is the common sauce. It is more economical to cut salt pork into small bits, and try it till the pork is brown and crispy. It should not be done too fast, lest the sweetness be scorched out.

60

Salted shad and mackerel should be put into a deep plate and covered with boiling water for about ten minutes after it is thoroughly broiled, before it is buttered. This makes it tender, takes off the coat of salt, and prevents the strong oily taste, so apt to be unpleasant in preserved fish. The same rule applies to smoked salmon.

Salt fish mashed with potatoes, with good butter or pork scraps to moisten it, is nicer the second day than it was the first. The fish should be minced very fine, while it is warm. After it has got cold and dry, it is difficult to do it nicely. Salt fish needs plenty of vegetables, such as onions, beets, carrots, &c.

There is no way of preparing salt fish for breakfast, so nice as to roll it up in little balls, after it is mixed with mashed potatoes; dip it into an egg, and fry it brown.

A female lobster is not considered so good as a male. In the female, the sides of the head, or what look like cheeks, are much larger, and jut out more than those of the male. The end of a lobster is surrounded with what children call 'purses,' edged with a little fringe. If you put your hand under these to raise it, and find it springs back hard and firm, it is a sign the lobster is fresh; if they move flabbily, it is not a good omen.

Fried salt pork and apples is a favourite dish in the country; but it is seldom seen in the city. After the pork is fried, some of the fat should be taken out, lest the apples should be oily. Acid apples should be chosen, because they cook more easily; they should be cut in slices, across the whole apple, about twice or three times as thick as a new dollar. Fried till tender, and brown on both sides - laid around the pork. If you have cold potatoes, slice them and brown them in the same way.

Pickles

84 …

When walnuts are so ripe that a pin will go into them easily, they are ready for pickling. They should be soaked twelve days in very strong cold salt and water, which has been boiled and skimmed. A quantity of vinegar, enough to cover them well, should be boiled with whole pepper, mustard-seed, small onions, or garlic, cloves, ginger, and horseradish; this should not be poured upon them till it is cold. They should be pickled a few months before they are eaten. To be kept close covered; for the air softens them. The liquor is an excellent catsup to be eaten on fish.

Appendix

121

Vegetable Oyster. This vegetable is something like a parsnip; is planted about the same time, ripens about the same time, and requires about the same cooking. It is said to taste very much like real oysters. It is cut in pieces, after being boiled, dipped in batter, and fried in the same way. It is excellent mixed with minced salt fish.

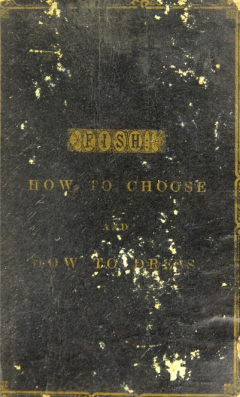

"Fish, How to Choose and How to Dress" (1843) William Hughes "Piscator" at pages 1 to 9

Click here to read online

Contents

Chapter I, Introductory Remarks, page 1

Chapter II, Directions for choosing fish, with observations upon their respective qualities; Fishes of the cod kind, page 10

Section II, Eels and lampreys, page 36

Section III, Fishes of the perch kind, and mullets both red and grey, also the sea bream and its varieties, page 47

Section IV, Of the wrasses, page 67

Section V, Gurnards, page 70

Section VI, Fishes of the carp kind, page 74

Section VII, Pikes and launces, page 87

Section VIII, Fishes of the mackerel kind, page 94

Section IX, Fishes of the herring kind, page 101

Section X, Fishes of the salmon kind, page 107

Section XI, Dories, page 117

Section XII, Fishes of the turbot and flounder kind, page 122

Section XIII, Fishes of the skate kind, page 134

Section XIV, Stragglers, or a few of all sorts, page 140

Section XV, How to choose salt fish, page 145

Section XVI, How to choose shell fish, page 149

CHAPTER III, How to clean and preserve fish, page 155

Section I, How to clean fish, page 155

Section II, How to cure fish, page 166

CHAPTER IV, On the cookery of fish, page 171

Section I, How to boil fish, page 174

Section II, How to fry fish, page 189

Section III, How to broil fish, page 214

Section IV, How to stew fish, page 220

Section V, How to curry fish, page 235

Section VI, How to roast and bake fish, page 237

Section VII, Fish pies and patties, page 248

Section VIII, How to dress shell fish, page 254

Section IX, Sauces for fish, page 267

Section X, Potting and pickling fish, page 272

Chapter I

Introductory Remarks

The object of writing the present work is to bring every kind of fish that is to he found in our waters and adapted for the food of man before the notice of the public. This, we must confess, is a task we could wish had been undertaken by abler hands, embracing, as it does, a subject that has been hut partially treated on by the numerous, as well as talented writers who have from time to time favoured us with their useful commentaries on the art of cookery. As a proof of the limited extent to which this important subject has been restricted, we find, even in the most celebrated cookery books, that out of upwards of one hundred and seventy distinct species of good and wholesome fishes with which our markets are supplied, scarcely one fourth part are mentioned even byname: a very multitude of fishes, all excellent in their way at their proper times and seasons are altogether omitted, whilst several that are highly esteemed, and so common as to he easily attainable - all capable of being cooked in a variety of ways, each furnishing a dish the most fastidious epicure could not forbear to praise - are merely glossed over as unworthy of further notice.

In no less than six justly esteemed works on the subject, we have searched in vain for some remarks upon the merits of that most delicious of fishes, the john dory, but whose name we can find no-where mentioned: whilst the mighty ling - the largest and in our humble opinion the best of the whole cod tribe - is only alluded to as "a dried salt fish" not one word being said about its edible qualities when fresh, though few fish are capable of being cooked in a greater variety of modes, or can be compared to a fresh ling in flavour in any one of them.

But it is not our intention to assail the able writers on the art of cookery for their omissions in the fish department; our sole object is to try as far as lies within our power and ability to supply them, and to furnish our readers with a sufficient stock of information to enable them to select, as also to prepare for the table, a most delicious as well as wholesome article of food, and one which now through the medium of our extensive railway communications, might with good management, and at no great expense, be distributed throughout the whole length and breadth of the land; by which means not only would the labouring and poorer classes receive a valuable augmentation to their humble fare at a cheap rate, but our fisheries - so important to us as a naval power, affording, as they do, the best nursery for seamen - would receive additional vigour by an increased demand for the produce of the hardy and industrious fishermen, which have been but too often found to lie almost as a dreg upon their hands, when supplied in great quantities; and thus oftentimes a valuable article of food is cast away to rot upon a dung-heap, that might have administered to the wants and comforts of hundreds of our starving fellow countrymen.

Much indeed then is it to be wished that the fish taken on our coasts could be better distributed throughout the country, and that all would lend their assistance to promote so desirable an end; for if there was only a demand, the supply, we are convinced, would not be long wanting - we are aware that there will be some prejudices to overcome, before the consumption will be so general as it ought to be, particularly among the humbler classes, who are very averse to vary their usual fare, whilst we all of us, rich as well as poor, are apt to think too lightly of those benefits that Providence bestows upon us with the most liberal hand: and thus it is, that many most excellent fishes are rejected by the more opulent classes, and are unthankfully eaten by the poor, for no other cause than the extreme ease and abundance with which the commodity can be supplied. This has been remarkably exemplified in the poor despised hake, which, until very recently, was never admitted to tables of the wealthy; though now its merits have begun to be more duly appreciated, and this fish, which formerly for its mere cheapness and plenty was scorned even by the poor, we have latterly had the gratification to see gracing the tables of some of the aristocracy of the land.

This, among many instances, far too numerous to mention, convinces us how desirable it is that the qualities of all our fishes should be more generally known, as also their proper times and seasons; and the criterions by which, not only they may be distinguished from, inferior kinds they closely resemble; but also such particular appearances as will denote with certainty the freshness and state and condition of the article. A knowledge of all these points must ever be of the greatest importance to the caterer of a family - one of the great causes why fish is not a more favorable article of diet, is owing to persons having partaken of it either when out of season, or from its being in a partial state of decomposition, from being too long or carelessly kept. The Salmon, which is justly styled the king of fishes, and entitled to vie if not surpass any of the scaly race when in its proper season, is one of the most disagreeable and unwholesome when out of condition - and when eaten stale is little better than poison. What indeed can be more delicious than a perfectly fresh mackerel, or more disgusting than one in the slightest degree tainted ? And the same observations are applicable to every other kind of fish we may chance to meet with; and which from their perishable nature, require the greatest care and attention to keep them in a sound state, even for a short space of time.

Here then arises another important point, viz. a knowledge of the different modes in which each different species may be best preserved, as well as cooked to the greatest possible advantage. Few fish, indeed, except in frosty weather, can be kept good for above two or three days, at the utmost, without the assistance of salt or some other artificial aid. Some indeed in warm weather become tainted even in the course of a single day after they are taken out of the water, though in many this may be prevented to a considerable extent, by removing the intestines within an hour or two after they are caught. This occurs particularly in the smaller species of the cod tribe; such as the whiting, or whiting-pout, as also in the haddock; as the livers of all these fishes contain a great quantity of oil, which in warm weather quickly imparts a rancid and disagreeable taste to the whole fish. Many other fishes also, that will be noticed hereafter, may be kept good a considerable time, particularly in moderate weather, after being gutted, which, if omitted, will cause the fish to become tainted in less than one half the time it would have done, had this necessary precaution been adopted.

Again, some fish that are excellent when salted and dried - as the torsk; or, even when only slightly powdered with salt for a day or two previously to their being dressed, as a whiting pollack for instance - are both watery, soft and insipid when cooked perfectly fresh; whilst in others the salt produces so contrary an effect as to extract every kind of flavour but its own ; or what is worse, imparts a rank and disagreeable taste, as it almost invariably does when applied in any considerable quantity for the purpose of preserving soles, and most other species of flat fish, for any length of time. Some particular kinds of fishes, as mackerel, herrings, or pilchards, cannot possibly be brought to table too soon after being taken from their native element; on which account it falls to the lot of but very few to partake of either of these kinds of fishes in their greatest perfection: this occurs more particularly with pilchards than any kind of fish whatever, as they acquire an oily taste in the course of a few hours after death, which, though some may admire, is very different from the fine curdy flavour they possess when just taken from the nets. In others again, as in all the scate tribe, there is a rank taste that is far more perceptible than pleasing, when they are dressed on the same day on which they are caught, yet, which wholly vanishes, if they are hung up in a cool place for a day or two.

Much also depends upon knowing in what way each particular fish may be cooked, so as to make its appearance to the greatest advantage; many there are that are unpalatable when dressed in one particular way, that are equally good if another mode of cookery he adopted - a stewed carp affords a really splendid dish; a boiled carp one of the worst that can be brought to table - the merits of a surmullet broiled, baked or fried, enveloped in white paper, with its liver for sauce, are too well known to require any comment from us, and yet, when simply boiled and gutted as you would a whiting, is a sad woolly and insipid affair; and the same observations hold equally in the case of a variety of other fishes we purpose fully treating of hereafter in their proper place.

With these preliminary remarks we shall at once proceed to our subject. First, by endeavouring to supply such practical directions as may afford the best assistance to enable our readers to distinguish the different kinds of fishes, with a few remarks on their respective merits as we proceed. The proper times and seasons, and the best criterions by which a sound and healthy condition may be most easily discovered - will then be discussed.

An attempt will next be made to point out the best modes of treatment for preserving fish, either for along or short period - as the exigency of the case may require - and the various modes by which this may be effected - and last of all, to furnish all the information we can collect, as to the various modes by which each individual species may appear at table in the most favourable point of view, as well as the different sauces with which they should be accompanied; a subject by no means to be passed lightly over, and which no pains shall be wanting on our part to lay fairly before our readers.

"Modern Cookery for Private Families" reduced to a system of easy practice in a series of carefully tested receipts in which the principles of Baron Liebig and other eminent writers have been as much as possible applied and explained (1845) Eliza Acton

Click here to read the entire text online.

Vocabulary of Terms at pages xiii and xiv

…

Court Bouillon - the preparation of vegetables and wine, in which (in expensive cookery) fish is boiled.

Matelote - a rich and expensive stew of fish with wine, generally of carp, eels, or trout.

| CHAPTER II Fish | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To choose Fish | 48 | Baked Whitings à la Française | 68 | |

| To clean Fish | 50 | To boil Mackerel (and when in season) | 69 | |

| To keep Fish | 51 | To bake Mackerel | 69 | |

| To sweeten tainted Fish | 51 | Baked Mackerel or Whitings (Cinderella's receipt. Good) | 70 | |

| The mode of cooking best adapted to different kinds of Fish | 51 | Fried Mackerel (Common French receipt) | 70 | |

| The best mode of boiling Fish | 53 | Fillets of Mackerel (fried or broiled) | 71 | |

| Brine for boiling Fish | 54 | Boiled fillets of Mackerel | 71 | |

| To render boiled Fish firm | 54 | Mackerel broiled whole (an excellent receipt) | 71 | |

| To know when Fish is sufficiently boiled, or otherwise cooked | 55 | Mackerel stewed with wine (very good) | 72 | |

| To bake Fish | 55 | Fillets of Mackerel stewed in wine (excellent) | 72 | |

| Fat for frying Fish | 55 | To boil Haddocks (and when in season) | 73 | |

| To keep Fish hot for table | 56 | Baked Haddocks | 73 | |

| To boil a Turbot (and when in season) | 56 | To fry Haddocks | 73 | |

| Turbot à la crème | 57 | To dress Finnan Haddocks | 74 | |

| Turbot au Béchamel | 57 | To boil Gurnards (with directions for dressing them in other ways) | 74 | |

| Mould of cold Turbot with Shrimp Chatney (refer to Chapter VI) | 57 | Fresh Herrings (Farleigh receipt and when in season) | 74 | |

| To boil a John Dory (and when in season) | 58 | To dress the Sea Bream | 75 | |

| Small John Dories baked (Good. Author's receipt) | 58 | To boil Plaice or Flounders (and when in season) | 75 | |

| To boil a Brill | 58 | To fry Plaice or Flounders | 75 | |

| To boil Salmon (and when in season) | 59 | To roast, bake or broil Red Mullet (and when in season) | 76 | |

| Salmon à la Genevese | 59 | To boil Grey Mullet | 76 | |

| Crimped Salmon | 60 | The Gar Fish (to bake) | 77 | |

| Salmon à la St. Marcel | 60 | The Sand Launce, or Sand Eel (mode of dressing) | 77 | |

| Baked Salmon over mashed Potatoes | 60 | To fry Smelts (and when in season) | 77 | |

| Salmon Pudding, to be served hot or cold (a Scotch receipt. Good) | 60 | Baked Smelts | 78 | |

| To boil Cod Fish (and when in season) | 61 | To dress White Bait (Greenwich receipt and when in season) | 78 | |

| Slices of Cod Fish fried | 61 | Water Souchy (Greenwich receipt) | 78 | |

| Stewed Cod | 62 | Shad, Touraine fashion (also à la mode de Touraine) | 79 | |

| Stewed Cod Fish in brown sauce | 62 | Stewed Trout (good common receipt and when in season) | 80 | |

| To boil Salt Fish | 62 | To boil Pike (and when in season) | 80 | |

| Salt Fish à la Maître d'Hôtel | 63 | To bake Pike (common receipt) | 81 | |

| To boil Cods Sounds | 63 | To bake Pike (superior receipt) | 81 | |

| To fry Cods' Sounds in batter | 63 | To stew Carp (a common country receipt) | 82 | |

| To fry Soles (and when in season) | 64 | To boil Perch | 82 | |

| To boil Soles | 64 | To fry Perch or Tench | 83 | |

| Fillets of Soles | 65 | To fry Eels (and when in season) | 83 | |

| Soles au Plat | 66 | Boiled Eels (German receipt) | 83 | |

| Baked Soles (a simple but excellent receipt) | 66 | To dress Eels (Cornish receipt) | 84 | |

| Soles stewed in cream | 67 | Red Herrings à la Dauphin | 84 | |

| To fry Whitings (and when in season) | 67 | Red Herrings (common English mode) | 84 | |

| Fillets of Whitings | 68 | Anchovies fried in batter | 84 | |

| To boil Whitings (French receipt) | 68 | |||

| CHAPTER III Dishes of Shell-Fish | ||||

| Oysters, to cleanse and feed (and when in season) | 85 | Hot crab or Lobster (in season during the same time as Lobsters) | 89 | |

| To scallop Oysters | 86 | Potted Lobsters | 90 | |

| Scalloped Oysters à la Reine | 86 | Lobster cutlets (a superior entrée) | 91 | |

| To Stew Oysters | 86 | Lobster sausages | 91 | |

| For curried Oysters see Chapter XVI | 87 | Boudinettes of Lobsters, Prawns or Shrimps (entrée, author's receipt) | 92 | |

| Oyster sausages (a most excellent receipt) | 87 | To boil Shrimps or Prawns | 93 | |

| To boil Lobsters | 88 | To dish cold Prawns | 93 | |

| Cold dressed Lobster and Crab | 88 | To shell Shrimps and Prawns quickly and easily | 93 | |

| Lobsters, fricasseed or au Béchamel (entrée) | 89 | |||

Chapter I, Soups at page 46 "Cheap Fish Soups"

…

CHEAP FISH SOUPS.

An infinite variety of excellent soaps may be made of fish, which may be stewed down for them in precisely the same manner as meat, and with the same addition of vegetables and herbs. When the skin is coarse or rank it should be carefully stripped off before the fish is used; and any oily particles which may float on the surface should be entirely removed from it.

In France, Jersey, Cornwall, and many other localities, the conger eel, divested of its skin, is sliced up into thick cutlets and made into soup, which we are assured by English families who have it often served at their tables, is extremely good. A half-grown fish is best for the purpose. After the soup has been strained and allowed to settle, it must be heated afresh, and rice and minced parsley may be added to it as for the turkey soup of page 32; or it may be thickened with rice-flour only, or served clear. Curried fish-soups, too, are much to be recommended.

When broth or stock has been made as above with conger eel, common eels, whitings, haddocks, codlings, fresh water fish, or any common kind, which may be at hand, flakes of cold salmon, cod fish, John Dories, or scallops of cold soles, plaice, &c., may be heated and served in it; and the remains of crabs or lobsters mingled with them. The large oysters sold at so cheap a rate upon the coast, and which are not much esteemed for eating raw, serve admirably for imparting flavour to soup, and the softer portions of them may be served in it after a few minutes of gentle simmering. Anchovy or any other store fish-sauce may be added with good effect to many of these pottages if used with moderation. Prawns and shrimps likewise would generally be considered an improvement to them.

For more savoury preparations, fry the fish and vegetables, lay them into the soup-pot, and add boiling, instead of cold water to them.

Chapter II, Fish at pages 48 to 84

Chapter III, Dishes of Shell-Fish at pages 85 to 93:

"What Shall We Have for Dinner ? Satisfactorily answered by numerous bills of fare for from two to eighteen persons" (1851) Catherine Dickens ("Lady Maria Clutterbuck")

Click here to read the "Bills of Fare" online.

Background to authorship

It is now believed that What Shall We Have For Dinner? was written by Dickens under the name Lady Maria Clutterbuck. For decades academics thought Dickens' wife, Catherine, wrote the book. But papers found by the great-great grandson of Mark Lemon, a Dickens' family friend, proves otherwise. The papers, written by Lemon's daughter Betty, describe how Mr and Mrs Dickens would retreat to the study to write down the recipes, reports The Times. And she describes how:

"Various recipes were discussed and eventually a cookery book was compiled. The book created quite a sensation, but how much greater it would have been if had been known that Charles Dickens himself had a finger in the pie. The secret was, however, strictly kept."

Tim Matthews, 73, Lemon's relation told The Times:

"I've had them since 1976 when my grandmother died but never got round to sorting them out. Some are quite scurrilous. When I read the scraps about Dickens and the cookery book I was very excited. I was going through hundreds of pages of family memories during a clear out to make space in the house."

Peter Ackroyd, a Dickens biographer, said: