Kent Coast Sea Fishing Compendium |

A Treatyse of Fisshynge |

TopIntroduction

A Treatyse of Fisshynge wyth an Angle (Juliana Barnes or Berners)

This work is universally regarded as being the first English book on angling. The supposed authoress was a lady named Juliana Barnes (or Berners), born towards the end of the fourteenth century at Roding-Berners in the Hundred of Dunmow, Essex. Her father was Sir James Berners, who was beheaded in 1388 as one of the evil advisers of Richard II. Although she is said to have been the Prioress of Sopwell Nunnery in Hertfordshire, a dependancy of the Abbey of St. Albans, no record exists of any such appointment in her name.

To this nun is attributed the Boke of St. Albans, the earliest sporting work in the language. The book obtains its name from having been printed in St. Albans in 1486 by an unknown printer who is generally styled "The Schoolmaster of St. Albans". It is divided into three parts: hawking, hunting and "coat-armour". In 1496 Wynkyn de Worde issued a second edition adding a fourth part, the Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle (angle is a hook).

Editor's note: (i) OE angel, ON öngull, literally 'fish-hook', used for the bend of a river or the land within such a bend: Angilterne 13th Century, Angletarn(e) 1573, Angle Tarn CUL.

"A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic" (1910) G. T. Zoëga at page 529

öngull, (plural önglar), masculine, fish-hook.

"A Compendious Anglo-Saxon and English Dictionary" (1848) Joseph Bosworth at page 32

Angel; genitive angles, masculine 'a hook, fishing hook' -twecca, -twicca, an, masculine 'a red worm used for a bait in angling or fishing'.

The claims of Juliana Berners to the authorship of the first part (hawking) rests principally on the closing lines of the discourse of hunting, which ends with: "Your playe for to wynne or that you come inne, explicit Dam Julyans Barnes in her boke of Huntyng."

As regards the Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle, the evidence is more shadowy still and rests on the ungallant hypothesis that (a) only a woman could have given such directions for making a rod, and (b) no man could have been guilty of so "delightful a non sequitur in many of the arguments."

Dit Boecxken (Matthias van der Goes)

An earlier book, Dit boecxken leert hoe men mach voghelen vanghen metten handen. Ende hoe men mach visschen vanghen meten handen. Ende oeck andersins. Ende oeck tot wat tyden vanden iare dat een yeghelyck visch tsynen besten is. Hier eyndet een boecxken dat seer profite-liick is voer ellen visschers, ende vogheleers. En dit boecxken heeft doen duicken Mathys vendergoes" (Dit Boecxken, literally, "This little book"), [1] was originally published in Flemish by Matthias van der Goes of Antwerp in 1492 and was translated by Alfred Denison in 1872 and privately published in that year as a limited edition of 25 privately-circulated copies. The translation is literally rendered, giving a very appropriate-sounding period feel to the text. According to Denison, Dit Boecxken was the earliest known publication dealing with fishing and field sports, on the grounds that the Treatise of Fishing with an Angle did not appear in the Boke of St. Albans until the edition of 1496.

Mānasōllāsa (King Sōmēśvara)

Letter from S. L. Hora (Director), Zoological Survey of India, Indian Museum, Calcutta 13, to Nature dated 12 December 1950 entitled "A Sanskrit Work on Angling of the Early Twelfth Century"

Bashford Dean's Bibliography of Fishes records an anonymous work entitled Dit boecxken leert hoe men mach voghelen vanghen metten handen ende hoe men mach visschen vanghen meten handen, ende oeck andersins and published at Antwerp in 1492 as the earliest known work on angling. In 1872, Alfred Denison, as editor, published "A literal translation into English of the earliest known book on fowling and fishing, written originally in Flemish and printed at Antwerp in the year 1492". The editors of Dean's Bibliography of Fishes have supplied the following useful information concerning another earlier book on angling:

"This Flemish tract appears to have priority over the 'Boke of St Albans', as far as fishing is concerned; that is, as a printed book. There are a number of early German versions, appearing under the title of 'Büchlin' or 'Fischbüchlin', published between 1552 and 1700. One of these is included in the Fischbach of Gregory Mangolt, published at Zurich in 1598. Three other editions are known: one in 4°, without place or date, having an identical title; the other, slightly changed in verbiage, in 1583 without place; and the third in 1584."

In the fourteenth edition of the Encyclopœdia Britannica (1, p. 932) more light is thrown on the Boke of St Albans, a part of the second edition of which was published in 1496. The manuscript is stated to be of the earlier part of the fifteenth century. There are, however, possibilities of still older manuscripts of this work.

The publication of the Sanskrit manuscript of Mānasōllāsa by King Sōmēśvara, son of King Vikramāditya VI of the later Chālukyas, in the Gaekwad's Oriental Series (Publication No XXVIII, Baroda, 1925) has brought to light a chapter on angling which gives details, almost modern in practice, about this pleasant pastime. Mānasōllāsa is an encyclopædic work and was composed in A.D. 1127. The kingdom of Sōmēśvara comprised practically the whole of the Deccan plateau and included the Godavari, Narbada, Tapti and Kristna river systems. It included the Maratti, Tamil and Telugu peoples and stretched from the east to the west coast of India.

The chapter on angling is entitled "Matsyavinōda", the pastime of angling. As many as thirty-seven species of Indian sporting fishes are mentioned. These are divided into marine, freshwater and anadromous kinds. They are then further divided into scaly and scaleless varieties, and each group is still further divided into large, medium and small according to size. From the etymological meanings of the fish names and other particulars given in the work about each kind, it has been possible to determine with a fair degree of certainity thirty-three out of thirty-seven species. The fishing tackle is dealt with under the three main components, namely, line, rod and hook. Various types of fibres for making a line are suggested, and their relative merits discussed. A solid bamboo shoot or a branch of a mangrove tree are suggested as suitable material for making a rod; types of suitable iron hooks are described.

For different groups of fishes different prescriptions are given for preparing groundbaits, and methods of feeding various species are separately described. Sōmēśvara also gives hints on the actual fishing technique and refers to details of ground bait, tackle, float, bait, casting the line, fish bite, striking a fish and playing a fish.

By studying inscriptions of irrigation tanks in southern India, it has been possible to give an evolutionary sequence of fishing in such tanks. There are inscriptions of the fifth and sixth centuries A.D., showing that irrigation tanks were maintained from the revenue derived from paddy cultivation. In an inscription of the middle of the tenth century, there is mention of a fisherman, but he is assigned the work of supplying wood for the repairs of boats used for the desilting of tanks, and is paid for his labour in paddy. A Tamil inscription of A.D. 1112 mentions revenue derived from fishing for the maintenance of the tank, which shows that the art of pond culture and angling had already progressed fairly far. King Sōmēśvara composed his Mānasōllāsa in 1127. In all the inscriptions of the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries, one finds that fishery revenue from irrigation tanks was sufficient for their maintenance. From this historical narrative, the art of sport fishing can definitely be assigned in southern India to the middle of the tenth century.

The work referred to here shows that the art of angling was developed in ancient India to a very high standard, for the methods described therein are quite in line with those used by anglers in India to-day. The gipsies of Europe, who use Mongolian, Hindi and other fragments of Asiatic languages, to-day practise the same methods as those described by King Sōmēśvara, and it is likely that they wandered from India to Europe and spread the art of angling there. The so-called "Thomas detective float" [2], a peacock feather type of float, is described in "Matsyavinōda" and is not an innovation of the nineteenth century. Full details of this work, with an atlas of fishes referred to therein, will appear in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal in due course."

[1] Editor's note: Dit Boecxken came from the press of Matthias Van der Goes who printed at Antwerp from 1472 to 1491, but it also contains the printer's mark of Godfridus Bach who married the widow of Van der Goes. The book was probably in type at the death of the latter and may be assigned, Mr Denison suggests, to the year 1492. In date it would therefore have the priority of The Book of St Albans as far as fishing is concerned; that is, as a printed book, for Richard de Fournival's La Vieille, ou les dernières amours d'Ovide ("The old or past loves of Ovid") takes precedence of both, as an early record of the sport. It contains 26 chapters, of a few lines each, giving recipes for artificial baits, unguents and pastes and, at the close, two pages are given to the periods at which certain fish are "at their best". Richard de Fournival was born on 10th October 1201 and died on 1st March 1260.

[2] Editor's note: for a full description of the "Thomas detective float" see Tank Angling in India (1887) by Henry Sullivan Thomas at pages 23 to 28

"A Treatyse of Fisshynge wyth an Angle" (1496)

attributed to Dame Juliana Barnes (Berners)Prologue

Solomon in his proverbs says that a good spirit makes a flowering age, that is, a happy age and a long one. And since it is true, I ask this question, "Which are the means and the causes that lead a man into a happy spirit?" Truly, in my best judgement, it seems that they are good sports and honest games which a man enjoys without any repentance afterward.

Thence it follows that good sports and honest games are the cause of a man's happy old age and long life.

And therefore, I will now choose among four good sports and honest games: to wit, of hunting, hawking, fishing, and fowling. The best, in my simple opinion, is fishing, called angling, with a rod and a line and a hook. And of that I will talk as my simple mind will permit, not only because of the reasoning of Solomon, but also for the assertion that medical science makes in this manner:

Si tibi deficiant medici, medici tibi fiant

Haec tria - mens laeta, labor, et moderata diaeta.Translation: If you fall short of doctors, physicians will be these three - the happy mind, work, and moderate diet.

You shall understand that this means, if a man lacks leech or medicine, he shall make three things his leech and medicine, and he will never need any more. The first of them is a happy mind. The second is work which isn't too onerous. The third is a good diet.

First, if a man wishes ever more to have merry thoughts and be happy, he must avoid all quarrelsome company and all places of debate, where he might have any causes to be upset. And if he wishes to have a job which is not too hard, he must then organise, for his relaxation and pleasure, without care, anxiety, or trouble, a cheerful occupation which gives him good heart and in which will raise his spirits.

And if he wishes to have a moderate diet, he must avoid all places of revelry, which is the cause of overindulgence and sickness. And he must withdraw himself to places of sweet and hungry air, and eat nourishing and digestible meats.

Now then, I will describe these sports or games to establish, as well as I can, which is the best of them; although the right noble and very worthy prince, the Duke of York, lately called the Master of Game, has described the pleasures of hunting, just as I would describe it and all the others.

Hunting

For hunting, to my way of thinking, is too laborious. The hunter must always run and follow his hounds, exercising and sweating heavily. He blows on his horn till his lips blister; and when he thinks he is chasing a hare, very often it is a hedgehog.

Thus he hunts and knows not what he is after. He comes home in the evening soaking through, scratched, his clothes torn, his feet wet, covered in mud. This hound lost and that one crippled. Such upsets and many others happen to the hunter which, for fear of the displeasure of the hunters, I dare not discuss.

Thus, in truth, it seems to me that this is not the best sport or game of the four mentioned.

Hawking

The sport of hawking is hard work and difficult too, it seems to me. For the falconer often loses his hawks, as the hunter his hounds. Then his game and pleasure is gone. Very often he shouts and whistles till he has a raging thirst. His hawk flies to a branch and ignores him. When he would have her fly at game, then she flies into a rage. With poor feeding she will get the frounce, the ray, the cray, and many other illnesses that cause them to die.

This proves that this is not the best sport and game of the four discussed.

Fowling

The sport and game of fowling seems to me the worst. For in winter season the fowler has no luck except in the hardest and coldest weather, which is burdensome.

When he would go to his traps, he cannot because of the cold. He makes many traps and snares, yet he fares badly. In the morning, the dew soaks him up to his thighs. I could say more, but will leave off for fear of upset. Thus, it seems to me that hunting and hawking and also fowling are so tiresome and unpleasant that none of them can succeed nor can they be the best way of bringing a man into a happy frame of mind, which is the cause of long life according to the said proverb of Solomon.

Fishing

It follows then without doubt that the best sport must be fishing with an angle. For every other kind of fishing is also exhausting and painful, often making folk wet and cold, which has been seen frequently to bring serious illness. But the angler need suffer no cold nor disease nor annoyance, unless he brings it on himself. For he may not lose at the most but a line or a hook, of which he may have plenty of his own making, as this simple Treatise shall teach him. Even then his loss is not serious. He may have no other annoyance, unless a fish break away after taking the hook, or he catches nothing; which are not serious annoyances. If he does not catch one fish he will catch another, so long as he follows the teaching of this Treatise; unless indeed there is nothing in the water. Even then he has a wholesome walk and is happy at his ease in the fresh air, sweet with the scent of meadow flowers, which gives him an appetite. He hears the melodious harmony of birds; he sees the young swans, herons, ducks, coots, and many other birds with their broods. This seems to me better than all the noise of hounds, the blasts of horns, and the birdcalls, that hunters, falconers, and wildfowlers can make.

If the angler catches fish no one is happier in spirit than he. Also whoever wishes to go angling must rise early, which is good for man in this way: that is to say, good for his soul for it shall make him holy; and his body healthy by making him whole; also it shall increase his goods for it shall make him rich. As the old English proverb has it: "Who rises early shall be holy, healthy, and happy."

Thus I have proved, as I set out to do, that the sport and game of angling is the very thing to induce in a man a merry spirit; which according to the said parable of Solomon and the said medical doctrine will give him a flourishing life and a long one. Therefore to all you who are virtuous, gentle, and freeborn I write and make this simple Treatise following, by which you may learn the full craft of angling to enjoy yourselves whenever you wish; to the intent that your old age may be the more flourishing and the longer to endure.

The Rod

If you would be skilled in angling, you must first learn to make your tackle, that is, your rod and your lines of different colours. After that, you must know how you should angle; in what place of the water, how deep, and what time of day, for what manner of fish, in what weather, how many impediments there are in the fishing that is called angling, and especially with what baits for each different fish in each month of the year, how you shall make your baits breed, where you will find the baits and how you will keep them.

And for the most crafty thing, how you are to make your hooks of steel and of iron - some for the artificial fly and some for the float and the ground-line, as you will hear afterward all these things talked about openly so that you may learn.

And how you should make your rod skilfully, here I shall teach you. You must cut, between Michaelmas and Candlemas (29 September and 2 February), a fair staff of a fathom and a half long (9ft) and as thick as your arm, of hazel, willow or ash and soak it in a hot oven and set it straight. Then let it cool and dry for a month. Take it and tie it tight with a cockshoot cord, and bind it to a form or a perfectly square, large piece of timber. Then take a plumb wire that is smooth and straight and sharp at one end. And after that, burn it in the lower end with a spit for roasting birds, and with other spits, each bigger than the last, and always the largest last so that you make your hole taper. Then let it lie still and cool for two days. Untie it then and let it dry in a house-roof in the smoke until it is thoroughly dry.

In the same season, take a good rod (fair yard) of green hazel, and soak it even and straight and let it dry with the staff. And when they are dry, make the rod fit the hole in the staff, into half the length of the staff. And to make the other half of the top section, take a fair shoot of blackthorn, crabtree, medlar, or juniper, cut in the same season, and well soaked and straight. And bind them together neatly so that the top section may go exactly all the way into the said hole.

Then shave your staff down and make it taper. Then bind the staff at both ends with long hoops of iron or laton (an alloy something between brass and pewter) and fasten in the neatest manner, with a spike in the lower end fastened with a catch so that you can take your top section in and out.

Then set your upper section a handbreadth inside the other end of your staff in such a way that the thickness of the sections matches. Bind your top section at the other end as far down as the joint with a cord of six hairs. Fix the cord and tie it firmly at the top, with a loop to fasten on your fishing line.

And so you will make yourself a rod so secret that you can walk with it, and no one will know what you are doing. It will be light and well balanced to fish with as you wish. And for your greater convenience, here is a picture of it as an example:

The Lines

After you have made your rod, you must learn to colour your lines of hair this way. First, you must take, from the tail of a white horse, the longest and best hairs that you can find; and the rounder it is, the better it is. Divide it into six bunches, and you shall colour every part by itself in a different colour - as yellow, green, brown, tawny, russet, and dusky colours.

And to make a good green colour on your hair, you shall do thus: take a quart of small ale and put it in a little pan, and add to it half a pound of alum. And put your hair in it, and let it boil softly half an hour. Then take out your hair and let it dry. Then take a pottle (half-gallon) of water and put it in a pan. And put in it two handfuls of weld (dyer's weed - Reseda luteola - a yellow dye) and press it with a tile-stone, and let it boil gently half an hour. And when it is yellow on the scum, put in your hair with half a pound of copperas (iron sulfate or green vitriol), beaten to powder, and let it boil gently "halfe a myle waye" (the time it takes to walk half a mile, about 10 minutes). And then set it down and let it cool five or six hours. Then take out the hair and dry it. And it is then the finest green there is for the water, and the more copperas you add to it, the better it is, or else instead use verdigris (made by hanging copper plates over hot vinegar in a sealed pot until a green crust formed on the copper).

Another way you can make a brighter green, thus: steep your hair in a woad (Isatis tinctoria) vat (wood cask) until it is a light blue-grey colour and then boil it in old weld (yellow vegetable dye) as I have described, except that you must not add to it either copperas or verdigris.

To make your hair yellow: prepare it with alum as I have explained already, and after that with old weld (yellow vegetable dye) without copperas or verdigris.

Another yellow you shall make thus: take a half a gallon of small ale (low-alcohol beer), and crush three handfuls of walnut leaves, and put them together. And put in your hair until it is as deep a yellow as you will have it.

To make russet hair: take a pint and a half of strong lye (caustic soda) and half a pound of soot and a little juice of walnut leaves and a quarter of a pound of alum (hydrated potassium aluminium sulfate) and put them all together in a pan and boil them well, and when it is cold, put in your hair till it is as dark as you will have it.

To make a brown colour: take a pound of soot and a quart of ale, and boil it with as many walnut leaves as you wish. And when they turn black, take it off the fire, and put your hair in it, and let it lie still till it is as brown as you will have it.

To make another brown: take strong ale and soot and blend them together, and put therein your hair for two days and two nights, and it will be a right good colour.

To make a tawny colour: take lime and water, and put them together and also put your hair therein four or five hours. Then take it out and put it in tanner's ooze (owser - the liquor of tanbark, a dye made from oak bark and water in which hides are soaked to give them an even shade of brown) a day, and it will be as fine a tawny colour as we need for our purpose.

The sixth part of your hair you must keep still white for lines for the dubbed hook, to fish for the trout and grayling, and for small lines to use for the roach and the dace.

When your hair is thus coloured, you must know for which waters and for which seasons they should be used:

- the green colour in all clear water from April till September;

- the yellow colour in every clear water from September till November, for it is like the weeds and other types of grass which grow in the waters and rivers, when they are broken;

- the russet colour serves all the winter until the end of April, as well in rivers as in pools or lakes;

- the brown colour serves for that water that is black, sluggish, in rivers or in other waters;

- the tawny colour for those waters that are heathy or marshy.

Now you must make your lines in this way. First, see that you have an instrument like the one shown in the following picture and it shall be made of wood, except the bolt underneath which must be of iron. Then take your hair and cut off from the small end a large handful or more, for it is neither strong nor yet sure. Then turn the top to the tail each in equal amount, and divide it into three parts. Then plait each part at the one end by itself, and at the other end plait all three together and put this same end in the other end of your instrument, the end that has but one cleft, and make the other end tight with the wedge four fingers from the end of your hair. Then twist each strand the same way and pull it tight and fasten them in the three clefts equally well. Then take out that other end and twist it whichever way it goes best. Then stretch it a little and plait it so that it will not come undone, and that is good.

And to know how to make your instrument, see, here it is in a picture:

(The basic idea is a bolt about the length of a horsehair, with at one end a cleft knob for fixing one end of the hair and, at the other end, there seems to be a little wheel, by which all the hairs could be twisted together producing a triple line made by plaiting three separate strands of horsehair, each hair first being doubled tip to root.)

When you have as many of the lengths as you suppose will suffice for the length of a line, then you must tie them together with a water knot or else a duchess knot. And when your knot is tied, cut off the unused ends a straw's breadth from the knot.

Thus you will make your lines fair and fine, and also completely secure for any type of fish. And because you should know both the water knot and also the duchess knot, behold them here in pictures - tie them in the likeness of the drawing: (neither image survives)

Water Knot: in the early 19th century fishermen referred to this knot as the water knot.

It has also been known as the angler's knot, the English knot, the Englishman's knot, the true lover's knot and the waterman's knot.The Hooks

You shall understand that the subtlest and hardest art in making your tackle is to make your hooks, for the making of which you must have suitable files, thin and sharp and beaten small, a semi-clamp of iron, a bender, a pair of long and small tongs, a hard knife, somewhat thick, an anvil and a little hammer.

And for small fish you shall make your hooks in this manner, of the smallest square needles of steel that you can find. You shall put the square needle in a red charcoal fire till it is of the same colour as the fire. Then take it out and let it cool, and you will find it well tempered for filing. Then raise the barb with your knife and make the point sharp. Then temper it again, for otherwise it will break in the bending. Then bend it like the bend shown here as an example.

And you shall make greater hooks in the same way out of larger needles such as embroiderers' or tailors' or shoemakers' needles. Spear points or shoemakers' needles especially are the best hooks for great fish. And see that they bend at the point when they are tested, otherwise they are not good. When the hook is bent, beat the hinder end out broad, and file it smooth to prevent fraying of your line. Then put it in the fire again and give it an easy red heat. Then suddenly quench it in water, and it will be hard and strong. And for you to have knowledge of your instruments, see them here in portrayed in the picture:

When you have made your hooks as you have been taught, then you must attach them to your lines, according to size and strength in this manner. You must take fine red silk, and if it is for a large hook, then double it, don't twist it. Otherwise, for small hooks, let it be single and with it, thickly bind the line there for a straw's breadth from the end of the hook where your line is placed.

Then set your hook there and wrap it with the same thread for two-thirds of the length that is to be wrapped. And when you come to the third part, turn the end of your line back upon the wrapping, double, and wrap it thus double for the third part. Then put your thread in at the loop twice or thrice, and let it go each time round about the shank of your hook. Then wet the loop and pull it until it is tight. And be sure that your line always lies inside your hooks and not outside. Then cut off the end of the line and the thread as close as you can without cutting the knot.

Now that you know how big a hook to angle with for every fish, I will tell you with how many hairs you must angle for every kind of fish. For the minnow, with a line of one hair. For the growing roach, the bleak, the gudgeon, and the ruffee, with a line of two hairs. For the dace and the great roach, with a line of three hairs. For the perch, the flounder, and small bream, with four hairs. For the chevin-chub, the bream, the tench, and the eel, with six hairs. For the trout, grayling, barbel, and the great chub, with nine hairs. For the great trout, with twelve hairs. For the salmon, with fifteen hairs. And for the pike, with a chalk line made brown with your brown colouring as described earlier, strengthened with a wire, as you will hear hereafter when I speak of the pike.

The Sinkers

Your lines must be weighted with lead, and you must know that the nearest sinker to the hook should be a full foot and more separated from it, and every sinker of a weight suitable for the thickness of the line.

There are three kinds of sinkers for a running ground-line. And for the float set upon the stationary ground-line ten weights all joining together. On the running ground-line, nine or ten small ones.

The float sinker must be so heavy that the least pluck of any fish can pull it down into the water. And make your weights round and smooth so that they do not stick on stones or on weeds. And for the better understanding see them here in these pictures:

The running ground line

The stationary ground line

The float line

The line for perch or tench

The line for a pike; lead, cork, and reinforced with wire

The Floats

Then you are to make your floats in this manner. Take a good cork that is clean without many holes, and bore it through with a small hot iron and put a quill in it, even and straight. The larger the float, the larger the quill and the larger the hole. Then shape it large in the middle and small at both ends, and especially sharp in the lower end, and similar to the pictures which follow:

And make them smooth on a grinding stone, or on a tile stone. And see that the float for one hair is no more than pea-sized; for two hairs - as a bean; for twelve hairs - as a walnut. And so every line according to proportion.

All kinds of lines that are not for the ground must have floats, and the running ground-line must have a float. The stationary ground-line doesn't need a float.

There are three kinds of sinkers for a running ground-line. And for the float set upon the stationary ground-line ten weights all joining together. On the running ground-line, nine or ten small ones.

The float sinker must be so heavy that the least pluck of any fish can pull it down into the water. And make your weights round and smooth so that they do not stick on stones or on weeds. And for the better understanding see them here in picture.

How to Angle

Now that I have taught you how to make all your tackle I shall tell you how to angle. There are six ways of angling:

- the first is at the bottom for the trout and other fish;

- another is at the bottom at an arch or at a pool, where it ebbs and flows, for bleak, roach, and dace;

- the third is with a float for all manner of fish;

- the fourth, with a minnow for the trout without lead or float;

- the fifth is running in the same way for roach and dace with one or two hairs and a fly;

- the sixth is with an artificial fly for the trout and grayling.

And for the first and principal point in angling, always keep away from the water, from the sight of the fish. Either keep back on the land or else behind a bush, so that the fish can't see you. For if they do, they will not bite. Also take care that your shadow does not fall on the water any more than it might, for that is a thing which will soon frighten the fish; and if a fish is frightened, he will not bite for a long time after.

For all kinds of fish that feed at the bottom, you must angle for them at the bottom, so that your hooks will run or lie on the bottom. And for all other fish that feed above, you must angle for them in the middle of the water, or somewhat beneath or somewhat above.

For the bigger the fish, the nearer he lies to the bottom of the water; and the smaller the fish, the more he swims above.

The third good point is when the fish bites, that you be not too quick to strike, nor too slow. For you must wait till you suppose that the bait is fairly in the mouth of the fish, and then wait no longer. And this is for the bottom. And for the float, when you see it pulled softly under the water or else carried softly upon the water, then strike. And see that you never strike too hard for the strength of your line, for fear of breaking it.

And if you have the fortune to hook a great fish with a small tackle, then you must lead him in the water and labour with him there until he is drowned and overcome. Then take him as well as you can or may, and always beware that you do not pull beyond the strength of your line. And as much as you can, do not let him come out of the end of your line straight from you, but keep him ever under the rod and always hold him there, so that your line can sustain and bear his leaps and his plunges with the help of your rod and of your hand.

Where to Fish

Where I will declare to you in what place of the water you must angle. You should angle in a pool or in standing water in every place where it is at all deep. There is not a great choice of places where a pool is of any depth. For it is but a prison for fish, and they live for the most part in hunger like prisoners, and therefore it takes the less art to catch them.

But in a river, you shall angle in every place where it is deep and clear by the bottom; for example, gravel or clay without mud or weeds. And especially if there is an eddy or a cover; for example, a hollow bank, or big roots of trees, or long weeds floating above in the water where the fish can cover and hide themselves at certain times when they like. Also it is good to angle in deep, swift streams, and also in waterfalls and weirs, and in floodgates and mill-races. And it is good to angle where the water rests by the bank and where the current runs close by and it is deep and clear at the bottom and in any other places where you can see any fish rise or feeding.

Now you must know what time of the day you should angle. From the beginning of May until it is September, the biting time is early in the morning from four o'clock until eight o'clock. And in the afternoon, from four o'clock until eight o'clock, but not so good as in the morning.

And if there is a cold, whistling wind and a dark, lowering day. For a dark day is much better to angle in than a clear day. From the beginning of September until the end of April, don't ignore any time of the day. Also many pool fishes will bite best at noontime.

And if at any time of the day you see the trout or grayling leap, angle for him with an artificial fly appropriate to that same month.

And where the water ebbs and flows, the fish will bite in some place at the ebb, and in some place at the flood. After that, they will rest behind stakes and arches of bridges and other places of that sort.

Here you should know in what weather you must angle. As I said before, in a dark, lowering day when the wind blows softly. And in summer season when it is burning hot, then it is no good. From September until April on a fair, sunny day, it is right good to angle. And if the wind in that season comes from any part of the east, the weather then is no good. And when it snows or hails, or there is a great tempest, with thunder or lightning, or sweltering hot weather, then it is no good for angling.

Now you must know that there are twelve kinds of impediments which cause a man to take no fish, without other common causes that may happen by chance:

- the first is if your tackle is not adequate nor suitably made;

- the second is if your baits are not good or fine;

- the third is if you do not angle in biting time;

- the fourth is if the fish are frightened by the sight of a man;

- the fifth, if the water is very thick, white or red from any recent flood;

- the sixth, if the fish cannot stir because of the cold;

- the seventh, if the weather is hot;

- the eighth, if it rains;

- the ninth, if it hails or snow falls;

- the tenth is if there is a tempest;

- the eleventh is if there is a great wind;

- the twelfth if the wind is in the east, and that is worst, for commonly, both winter and summer, the fish will not bite then.

The west and north winds are good, but the south is best.

And now that I have told you, in all points, how to make your tackle and how you must fish with it, it makes sense that you should know with what baits you must angle for every kind of fish in every month of the year, which is the effect of the art. And without these baits being well known by you, all your other skills taught until now will not be of much use. For you cannot bring a hook into a fish's mouth without a bait. Baits for every kind of fish and for every month follow here in this way.

Fishes

Salmon

Because the salmon is the most stately fish that any one can angle for in fresh water, therefore I intend to begin with him. The salmon is a noble fish, but he is difficult to catch. For commonly he lies only in deep places of great rivers. And for the most part he keeps to the middle of the water, so that a man cannot come at him. And he is in season from March until Michaelmas, in which season you should angle for him with these baits when you can get them:

- first, with a red worm in the beginning and end of the season;

- and also with a grub that grows in a dunghill; and

- especially with an excellent bait that grows on a water dock.

And he doesn't bite at the bottom but at the float. Also you may take him, but it is seldom seen, with a dubbed hook at such times as he leaps, in the same style and manner as you catch a trout or a grayling.

And these baits are well proven baits for the salmon.

Trout

The trout, because he is a right dainty fish and also a right fervent biter, we shall speak of next. He is in season from March until Michaelmas. He is on clean gravel bottom and in a stream. You can angle for him at all times with a lying or running ground-line except in leaping time and then with a dubbed hook and early with a running ground-line, and later in the day with a float line.

You shall angle for him in March with a minnow hung on your hook by the lower nose, without float or sinker, drawing it up and down in the stream till you feel him take. In the same time, angle for him with a ground-line with an red worm as the most sure.

- in April, take the same baits, and also the lamprey, otherwise named "seven eyes", also the cankerworm that grows in a great tree, and the red snail;

- in May take the stone fly and the grub under the cow turd, and the silkworm, and the bait that grows on a fern leaf;

- in June, take a red worm and nip off the head, and put a codworm on your hook before it;

- in July, take the great red worm and the codworm together;

- in August, take a flesh fly and the big red worm and bacon fat, and bind them on your hook;

- in September, take the red worm and the minnow;

- in October, take the same, for they are special for the trout at all times of the year.

From April to September the trout leaps, then angle for him with dubbed hook appropriate to the month. These dubbed hooks you will find at the end of this treatise, and the months with them.

Grayling

The grayling, by another name called umber, is a delicious fish to man's mouth. And you can catch him just as you can the trout. And these are his baits:

- in March and in April, the red worm;

- in May, the green worm: a little ringed worm, the dock canker, and the hawthorn worm;

- in June, the bait that grows between the tree and the bark of an oak;

- in July, a bait that grows on a fern leaf and the big red worm, and nip off the head and put a codworm on your hook before it;

- in August, the red worm, and a dock worm.

And all the year afterward, a red worm.

Barbel

The barbel is a sweet fish, but it is a queasy food and a dangerous one for man's body. For commonly, he introduces the fevers. And if he is eaten raw, he may be the cause of a man's death which often has been seen. These are his baits:

- in March and in April, take fair fresh cheese, lay it on a board and cut it in small square pieces the length of your hook. Then take a candle and burn it on the end at the point of your hook until it is yellow. And then bind it on your hook with arrow maker's silk, and make it rough like a welbede. This bait is good for all the summer season;

- in May and June, take the hawthorn worm and the big red worm and nip off the head and put a codworm on your hook before them and that is a good bait;

- in July, take the red worm chiefly and the hawthorn worm together. Also the water-dock leaf worm and the hornet worm together;

- in August, and for all the year, take mutton fat and soft cheese, of each the same amount, and a little honey and grind or beat them together a long time, and work it until it is tough. Add to it a little flour and make it into small pellets. And that is a good bait to angle with at the bottom. And see that it sinks in the water, or else it is not good for this purpose.

Carp

The carp is a dainty fish, but there are only a few in England, and therefore I will write the less of him. He is an evil fish to take. For he is so strongly armoured in the mouth that no light tackle may hold him. And as regards his baits, I have but little knowledge of it, and I am reluctant to write more than I know and have tried.

But well I know that the red worm and the minnow are good baits for him at all times as I have heard reliable persons tell and also found written in books of credence.

Chub

The chub is a stately fish and his head is a dainty morsel. There is no fish so greatly armoured with scales on the body. And because be is a strong biter he has the more baits, which are these:

- in March, the red worm at the bottom for commonly he will bite these and at all times of the year if he is at all hungry;

- in April the ditch grub that grows in the tree, a worm that grows between the bark and the wood of an oak. The red worm and the young frogs when the feet are cut off. Also, the stone fly, the grub under the cow turd, the red snail;

- in May, put together on your hook the grub that breeds on the osier leaf and the dock worm. Use also the worm that breeds on the fern leaf, the caddis worm, and a grub that breeds on the hawthorn; or use a grub that breeds on an oak leaf, a silkworm, and a caddis worm all together;

- in June, take the cricket and the dor (dung beetle) and also a red worm, the head cut off, and a codworm before it and put them on the hook. Also a bait on the osier leaf, young frogs with three feet cut off at the body, and the fourth at the knee. The bait on the hawthorn and the codworm together, and a grub that breeds in a dunghill, and a large grasshopper;

- in July, the grasshopper and the bumblebee from the meadow; also young bees and young hornets and a great, brindled fly that grows in paths of meadows, and the fly that is found on anthills;

- in August, take wortworms (caterpillars) and maggots until Michaelmas;

- in September, the red worm. And also take these baits when you can get them, that is to say cherries, young mice without hair, and the honeycomb.

Bream

The bream is a noble fish and a dainty one (good to eat). You should angle for him from March until August with a red worm, and then with a butterfly and a green fly, and with a bait that grows among green reeds and a bait that grows in the bark of a dead tree. For young bream use maggots. For the rest of the year use the red worm and, in rivers, brown bread. There are other baits, but they are not easy, and therefore I shall pass over them.

Tench

A tench is a good fish and heals all sorts of other fish that are hurt if they can come to him. (It was believed that the grease on the skin of a tench was a healing ointment which wounded fish would rub themselves against. The popular belief is mentioned by Izaak Walton.) He is the most part of the year in the mud. And he stirs most in June and July and in other seasons but little. He is a poor biter. His baits are these:

- for all the year brown bread toasted with honey in the likeness of a buttered loaf and the great red worm; and

- for the best bait take the black blood in the heart of a sheep and flour and honey. Work them all together somewhat softer than paste, and anoint therewith the red worm, both for this fish and for others. And they will bite much better thereat at all times.

Perch

The perch is a dainty fish and passing wholesome, and a free biter. These are his baits:

- in March, the red worm;

- in April, the grub under the cow turd;

- in May, the sloe-thorn worm and the codworm;

- in June the bait that grows in an old fallen oak, and the green canker;

- in July, the bait that grows on the osier leaf and the grub that grows on the dunghill and the hawthorn worm, and the codworm;

- in August, the red worm and maggots. All the year after, the red worm is best.

Roach

The roach is an easy fish to catch. And if he is fat and penned up, then he is good food, and these are his baits:

- in March, the readiest bait is the red worm;

- in April, the grub under the cow turd;

- in May, the bait that grows on the oak leaf and the grub in the dunghill;

- in June, the bait that grows on the osier and the codworm;

- in July, houseflies and the bait that grows on all oak, and the nutworm and mathewes and maggots till Michaelmas.

And after that, the fat of bacon.

Dace

The dace is a noble fish to take, and if it be well fattened, then he is good eating.

- in March, the best bait is an red worm;

- in April, the grub under the cow turd;

- in May the dock canker and the bait on the sloe thorn and on the oak leaf;

- in June, the codworm and the bait on the osier and the white grub in the dunghill;

- in July take houseflies, and flies that grow in anthills, the codworm and maggots until Michaelmas. And if the water is clear, you shall catch fish when others take none.

And from that time forth, do as you do for the roach. For commonly in their biting and their baits they are alike. Also you may take him, but it is seldom seen, with a dubbed hook at such times as he leaps, in the same style and manner as you catch a trout or a grayling.

Bleak

The bleak is but a feeble fish, yet he is wholesome.

His baits from March to Michaelmas are the same as I have written before for the roach and dace, except that, all the summer season, as much as you may angle for him with a housefly, and, in the winter season, with bacon and other bait made as you will know after.

Ruffe

The ruffe is a right wholesome fish. And you shall angle to him with the same baits in all seasons of the year in the same way as I have told you of the perch for they are alike in fishing and feeding except that the ruffe is smaller. And therefore he must have the smaller bait.

Flounder

The flounder is a wholesome fish and a free and subtle biter in his manner. For usually, when he sucks in his food, he feeds at the bottom, and therefore you must angle for him with a lying ground-line. And he has but one manner of bait, and that is a red worm, which is the best bait for all kinds of fish.

Gudgeon

The gudgeon is a good fish for his size, and he bites well at the bottom. And his baits for all the year are these: the red worm, codworm and maggots. And you must angle for him with a float, and let your bait be near the bottom or else on the bottom.

Minnow

The minnow, when he shines in the water, then he is better. And though his body is little yet he is a ravenous biter and eager. And you shall angle for him with the same baits that you do for gudgeon, saving that they must be small.

Eel

The eel is a queasy fish, a glutton, and a devourer of the young fry of fish. And, as the pike also is a devourer of fish, I put them both behind all others for angling. For this eel, you must find a hole in the bottom of the water, and it is blue-blackish. There put in your hook till it be a foot within the hole, and your bait should be a great angle worm or a minnow.

Pike

The pike is a good fish, but because he devours so many of his own kind as of others, I love him the less. And to catch him, you shall do thus. Take a codling hook and take a roach or a fresh herring and a wire with a loop in the end and put it in at the mouth and out at the tail down by the back of the fresh herring. And then put the line of your hook in after, and draw the hook into the cheek of the fresh herring. Then put a lead weight on your line a yard away from your book, and a float midway between; and cast it in a hole where the pike lie. And this is the best and surest way for catching the pike.

Another manner of taking him is this: take a frog and put it on your hook between the skin and the body on the back half, and put on a float a yard away, and cast it where the pike lies, and you shall have him.

Another way - take the same bait and put it in asafetida and cast it in the water with a cord and a cork, and you shall not fail to get him.

And if you wish to have a good sport then tie the cord to a goose's foot, and you will see a good tussle to decide whether the goose or the pike will have the better of it.

Now you know with what baits and how you shall angle to every kind of fish.

Now I will tell you how you shall keep and feed your live baits. You shall feed and keep them all together, but each kind by itself with such things in and on which they breed.

And as long as they are alive and fresh, they are fine. But when they are sloughing their skin or else dead they are nothing. Out of these are excepted three kinds: that is, to wit of hornets, bumblebees, and wasps. These you must bake in bread, and after dip their heads in blood and let them dry.

Also except maggots, which, when they are grown large with their natural feeding, you must feed further with mutton fat and with a cake made of flour and honey, then they will become larger. And when you have cleansed them with sand in a bag or blanket, kept hot under your gown or other warm thing for two hours or three, then they are best and ready to angle with.

And of the frog cut off the leg at the knee, of the grasshopper the legs and wings at the body.

These baits are made to last all the year: the first are flour and lean meat from the thigh of a rabbit or a cat, virgin wax, and sheep's fat, and bray them in a mortar and then temper it at the fire with a little purified honey and so make it up into little balls, and bait your hooks with it according to their size. And this is a good bait for all manner of fresh fish.

Another, take the suet of a sheep and cheese in equal amounts and bray them together for a long while in a mortar. And take then flour and temper it therewith, and after that mix it with honey and make balls of it. And that is especially for the barbel.

Another for dace and roach and bleak: take wheat and seethe it well and then put it in blood for a whole day and a night, and it is a good bait.

For baits for great fish, keep specially this rule: when you have taken a great fish, open up the maw, and whatever you find therein, make that your bait, for it is best.

The Flies

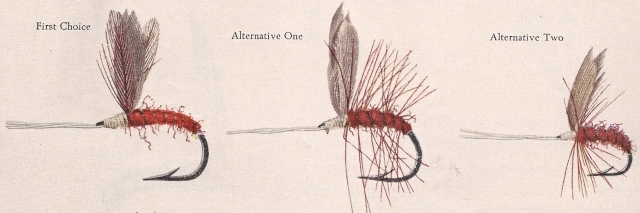

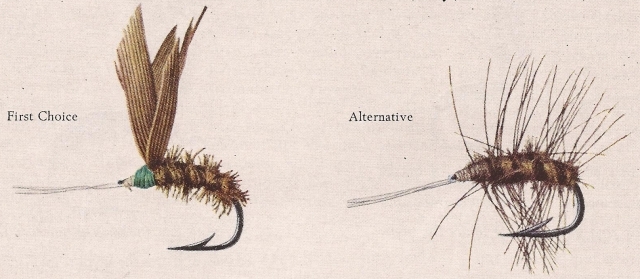

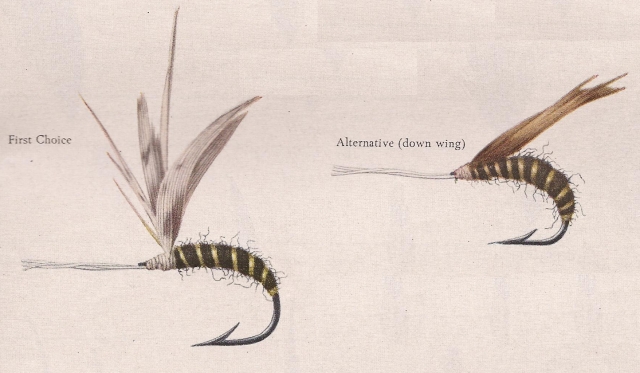

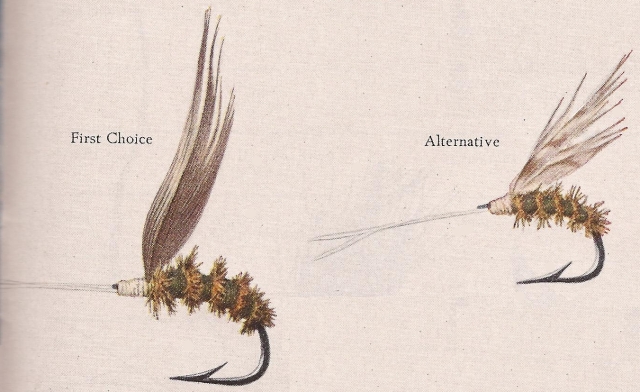

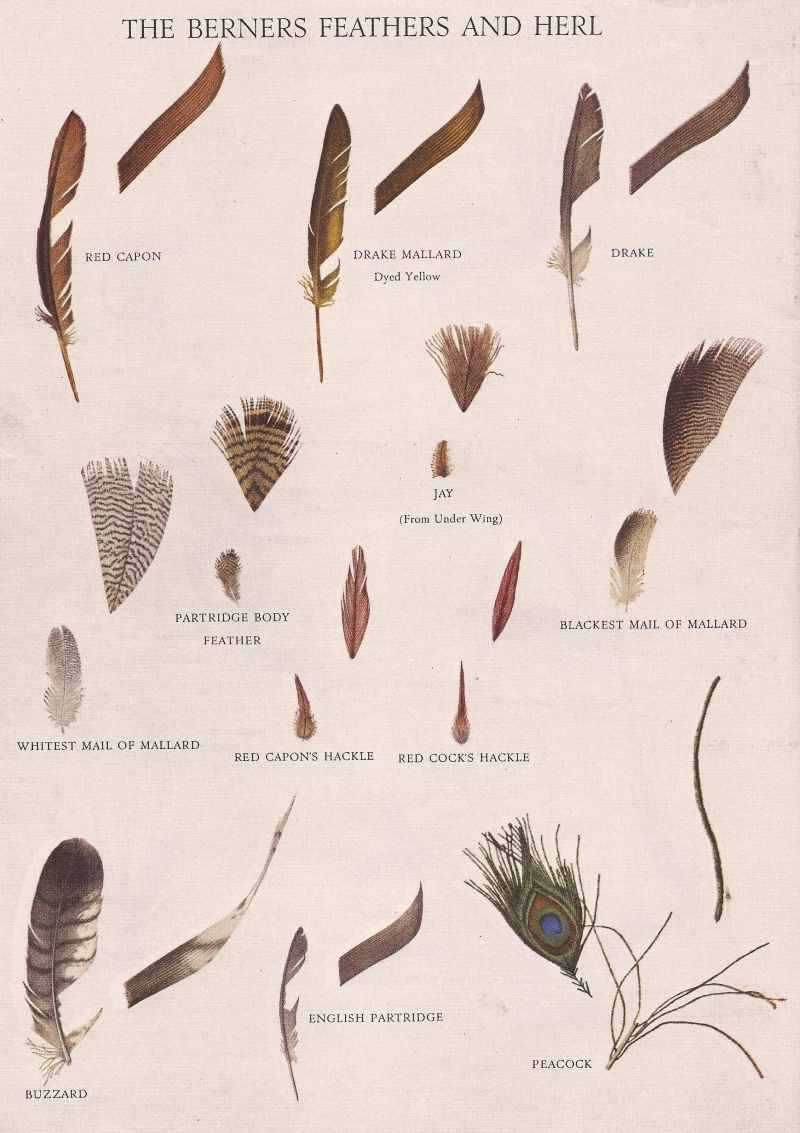

These are the twelve flies with which you shall angle for the trout and grayling and dub them like you will now hear me tell:

March

The dun fly the body of dun wool and the wings of the partridge.

March

Another dun fly, the body of black wool, the wings of the blackest drake, and the jay under the wing and under the tail.

April

The stone fly, the body of black wool, and yellow under the wing and under the tail, and the wings, of the drake.

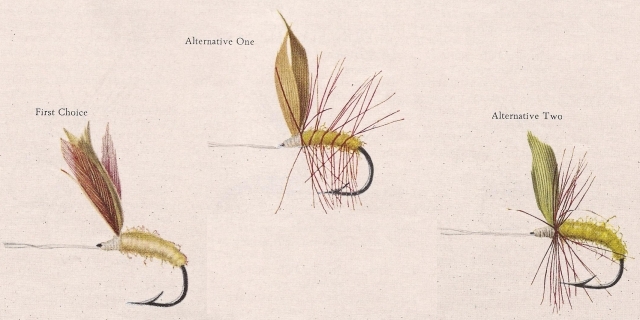

May

In the beginning of May, a good fly, the body of reddened wool and lapped about with black silk, the wings, of the drake and the red capon's hackle.

May

The yellow fly, the body of yellow wool, the wings of red cock hackle and of the drake dyed yellow.

May

The black leaper, the body of black wool and lapped about with the herl of the peacock's tail and the wings of the red capon with a blue head.

June

The dun cut: the body of black wool, and a yellow stripe after either side, the wings of the buzzard, bound on with barked hemp.

June

The maure fly: the body of dusky wool, the wings of the blackest male of the wild drake.

June

The tandy fly at St. William's Day: the body of tandy wool, and the wings contrary either against the other, of the whitest breast feathers of the wild drake.

July

The wasp fly: the body of black wool and lapped about with yellow thread, the wings of the buzzard.

July

The shell fly at St. Thomas' Day: the body of green wool and lapped about with the herl of the peacock's tail, wings of the buzzard.

August

The drake fly: the body of black wool and lapped about with black silk, wings of the breast feathers of the blackest drake, with a black head. These figures are put here in example of your hooks.

Epilogue

Here follows the order made to all those who shall have the understanding of this aforesaid treatise and use it for their pleasures.

You that can angle and catch fish for your pleasure, as the aforesaid treatise teaches and shows you. I charge and require you in the name of all noble men that you do not fish in any poor man's private water, as his pond, stew or other necessary things to keep fish in without his license and good will.

Nor that you use not to break any man's engines lying in their weirs and in other places due to them. Nor to take the fish away that is taken in them. For after a fish is taken in a man's trap, if the trap is laid in the public waters or else in such waters as he hires, it is his own personal property. And if you take it away, you rob him which is a right shameful deed for any gentleman to do, that the thieves and robbers do, who are punished for their evil deeds by the neck and otherwise when they can be found and captured.

And also if you do in like manner as this treatise shows you you will have no need to take other men’s fish, while you will have enough of your own catching, if you wish to work for them.

It will be a true pleasure to see the fair, bright, shining-scaled fishes deceived by your crafty means and drawn upon the land. Also, I charge you, that you break no man's hedges in going about your sports nor open any man's gates but that you shut them again.

Also, you must not use this aforesaid artful sport for covetousness to increasing or saving of your money only, but principally for your solace and to promote the health of your body and specially of your soul. For when you propose to go on your sports in fishing, you will not desire greatly many persons with you, which might hinder in letting you at your game.

And then you can serve God devoutly by earnestly saying your customary prayers. And thus doing, you will eschew and avoid many vices, such as idleness, which is the principal cause to induce man to many other vices, as is right well known.

Also, you must not be too greedy in catching your said game as taking too much at one time, which you may easily do if you do in every point as this present treatise shows you in every point. Which could easily be the occasion of destroying your own sport and other men's also.

As when you have a sufficient mess you should covet no more as at that time. Also you shall help yourself to nourish the game in all that you may, and to destroy all such things as are devourers of it. And all those that do as this rule shall have the blessing of God and St. Peter, which he grants them that with his precious blood he bought.

And so that this present treatise should not come into the hands of every idle person who would desire it if it were printed alone by itself and put in a little pamphlet, therefore I have compiled it in a greater volume of diverse books concerning gentle and noble men, to the end that the aforesaid idle persons which should have but little measure in the said sport of fishing should not by this means utterly destroy it.

The End

"The Writing of the Treatise" by Alfred Duggan

Sports Illustrated (13 May 1957)What follows is the product of two years of research. The story of Dame Juliana Berners, creator in literature of the world's first true artificial trout flies and the progenitor of the vast amount of angling literature which followed, was produced under the editorship of John McDonald, one of America's foremost students and writers on angling. Alfred Duggan, Britain's eminent medievalist and author, discusses Dame Juliana in Part I of the series, and presents a new rendering of her Treatise of Fishing with an Angle in Part II. In Part III, the Berners flies themselves are reconstructed on the basis of exacting research, tied by Professor Dwight A. Webster of Cornell University and painted in full color by John Langley Howard. In conclusion, Mr. McDonald, in a unique essay, ranges over the entire vast field of angling literature since Berners.

This famous little book, the first to give instructions in the art of tying artificial flies, has been available in print for more than 450 years. But, as with many other ancient documents, the identity of the author is in doubt. What is definitely known of the appearance of the Treatise may be summarized as follows:

In 1486 the schoolmaster of St. Albans Abbey, who managed the second press set up in England, published a bestseller. At that time it was unusual to print original compositions; most early printed books are versions of classics long famous in manuscript. This bestseller was a hitherto unknown work, taken from an obscure manuscript then preserved at St. Albans; since it lacked an earlier title it was known simply as the Book of St. Albans.

The book, written in English, treated of hunting, hawking and heraldry; it was said to have been composed a generation earlier by Dame Juliana Berners O.S.B., late Prioress of Sopwell.

It appealed to a wide public because the chapter on hunting gave sensible advice in everyday language. Probably it revealed nothing that the experienced huntsman did not know already, but its sidelights on etiquette and on the correct use of technical terms would be valuable to wealthy merchants who about this time began to mingle with the aristocracy.

This was before the days of copyright. Wynkyn de Worde, the businessman from Worth in Alsace who was first Caxton's partner and later his successor, printed another edition in 1496. In this version appears for the first time the Treatise of Fishing with an Angle, which purports to be another essay by the same author.

In 1532-34 Wynkyn de Worde published the Treatise of Fishing with an Angle as a separate work in quarto form. This is the edition I have used in this article. Since then the Treatise has always been in print. Throughout the 16th century new editions appeared. Other publishers attributed the whole Book of St. Albans to a mythical Sir Tristram, a knight of King Arthur's Round Table. It was believed that Sir Tristram of Lyonesse had invented the thousands of technical terms in which Tudor sportsmen delighted; and, since many of these terms were first written in the Book of St. Albans (though in speech they must be much older), the story got around that Sir Tristram was its author.

Dame Juliana does not appear in any contemporary document, or in the later list of the Prioresses of Sopwell or the genealogy of the Berners family. Some historians are troubled by the title "Dame," which is seldom found before the 16th century. So it is not surprising that many scholars have doubted the existence of Dame Juliana Berners.

But the argument from silence is always weak, and I am inclined to believe in Juliana. If the schoolmaster of St. Albans found an anonymous manuscript there was no reason why he should not publish it as anonymous; if he wanted a fictitious author it would be natural to father it on a monk of his own community. On the other hand, if he was reluctant to attribute a sporting work to a monk, for fear of causing scandal, the same reason would make him unwilling to attribute it to a nun. If he needed a name for his title page, why not give it to Sir Tristram or Sir Geoffrey de Mandeville?

The Berners genealogy was drawn up to enumerate the ancestors of the house; it might reasonably omit as irrelevant a nun who died childless and unmarried. The annals of Sopwell show a gap for the years 1430-1480, the very period when Dame Juliana would have flourished. "Dame," from the Latin domina, is still the official title of Benedictine choir-nuns, though in most other orders the female religious are called Mother or Sister.

This is the common tradition concerning Dame Juliana's birth and ancestry. Sir James Berners, a well-authenticated historical figure, had by his wife, Anne Berew, three sons (and perhaps this putative daughter). In 1388 he was executed as one of the "evil counselors" of King Richard II. But under King Henry IV the family was restored to favour; the Berners estates were returned, and Sir Richard, eldest son of the executed Sir James, was created a baron.

The Book of St. Albans is written in the English of about 1450 or earlier, so Juliana must have been in the nursery when her father met his end. It is likely that she was born about 1385 and died about 1460. When she was a young girl, circa 1400, there would have been no dowry for her, and therefore no chance of her finding a husband. But her family was popular at court. She may have lived in the royal household, and gone stag hunting and hawking in state with King Henry IV. Stag hunting was the privilege of kings and great lords; only someone who had moved in royal circles could write a book about it. But we do not know how old Juliana was when she took her vows; she may have hunted for several seasons before she entered religion.

The text of her Treatise contains one clue to its date of composition: she refers to "that right noble and full worthy prince the Duke of York, late called the Master of the Game." This seems to be a reference to Edward, grandson of Edward III and second Duke of York. Edward died in 1415, which, it happens, was also the year Juliana entered the nunnery at Sopwell. There was, of course, another Duke of York after Edward's death; but to the end of her life when Juliana spoke of the Duke of York, she would mean the "Master of the Game," the famous huntsman who taught the laws of the chase to a gay young debutante.

Assume then that Juliana Berners, of good birth but too poor to marry, entered the small nunnery of Sopwell about 1415. It lay just outside the great Abbey of St. Albans, whose abbot appointed the prioress. There is no record of serious scandal, but it was a lax and comfortable house. In 1338 the Abbot of St. Albans, as visitor, decreed that in future the garden might not be opened before the canonical hour of None (about 2:30 p.m.), and must be closed at curfew, which suggests that the ladies had been in the garden when they ought to have been in choir. The River Ver ran through this garden.

About 1440 Dame Juliana was, we assume, appointed prioress. She occupied her old age by composing treatises on the sports that had amused her youth, and copies of these manuscripts lay about in the parlour for 35 years until the schoolmaster of the neighbouring abbey came upon them and considered them worth printing. It all fits well enough.

In treating of hunting and hawking she recalled her girlhood in the fashionable world. But there was then good fishing in the Sopwell garden, no canon forbids nuns to fish, and it is likely that she fished, or pottered on the riverbank, until at last she died of old age.

She wrote of "Fishing with an Angle"; that means fishing with a hook, as opposed to fishing with nets or other implements. For the upper classes, this was a comparatively new amusement, and hers is the first known book of instructions; for the first time it is assumed that men well enough educated to read for pleasure will want to go fishing. The new pastime had a considerable vogue. In 1483 King Edward IV caught the chill that caused his death at a fishing picnic on the Thames near London. There is no record that any earlier king of England fished for amusement.

But it is obvious that a long unwritten tradition had come down to the gentle prioress. For many generations travellers, outlaws on the run and soldiers foraging for food had carried hooks in their pouches; burdensome nets, too heavy for the wayfarer, were left to the professionals who lived by the waterside. Dame Juliana did not herself devise all the technical tricks she advocates; in particular, the queer composite baits she advises for float-fishing must have been first put together by hoary old water bailiffs intent on proving to their lords that the business of taking fish is more difficult than it seems.

Nuns are notorious for petty economies, and in the Middle Ages there were at least a hundred days in every year, counting Lent, Advent, Ember Days, all Fridays and the vigils of great feasts, when butcher's meat would be forbidden. That explains why Dame Juliana gives instructions for catching coarse fish which nowadays no one eats willingly. Minnows were presumably intended as bait for something better, but roach and dace were for the table of the unlucky ladies. They must sometimes have wished that their superior had chosen another hobby.

In the 15th century it was a mark of gentle breeding to be able to perform all the professional duties of sport better than the professional. Any vulgar rich man could buy good hounds or good hawks; only a gentleman or a professional could train a puppy or man an eyas. Furthermore, there were no shops dealing in sporting equipment. Dame Juliana therefore begins at the beginning, with instructions on how to manufacture rods and tackle.

The first necessity is the rod. It must be long, for there is no reel, and the line is tied directly to it. The foundation is a considerable piece of timber: a pole of hazel, willow or ash nine feet long and as thick as your arm. This must be cut in midwinter when the sap is dormant, then straightened in the heat of an oven and seasoned for a month in a cool dry place. You next bore a hole right through the center, from end to end, with a red-hot wire. This hole is enlarged by the use of progressively larger spits, beginning with the little spit on which small birds are roasted. (Any good kitchen would have a wide range of spits.) You then season your rod once more in wood-smoke. At the upper end a yard-long switch of seasoned hazel is inserted. At the top, and perhaps also at the bottom, a "crop" is fixed, made from seasoned blackhorn, crabtree, medlar, or juniper and bound with horsehair. Your line will be fixed to the binding at the top of this crop. The whole is strengthened at top and bottom by iron ferrules.

The final result is a strong springy rod all of 10 feet long, reinforced by bindings of horsehair and metal. The author claims that it can be easily taken down and assembled, and that when it is used as a walking stick no passer-by will recognize it for a fishing rod. This last seems a direct encouragement to poaching, but I find it hard to credit.

All this skilled joinery is to be done at home by the prospective fisherman himself.

The line also is made at home, of hair from the tail of a white horse. It may be dyed any one of six colours and, of course, the dyes must be fast. Instructions are given for compounding dyes from ingredients that would be found in any well-equipped kitchen; for it was then the custom to dye cloth at home. The colours required are yellow, green, brown, tawny, russet and dark grey, to be used in the appropriate state of the water.

Your line may be of any gauge from 15 horsehairs to one, according to the size of the quarry. Of course, the individual hairs will not be more than two to three feet long, so frequent knots will be necessary. To twist the hairs into a line, Juliana gives a picture of a most ingenious tool, a miniature rope-walk. The basic idea is that the hairs are held fast at one end of a short rod, and all twisted together on a little catch. She points out, with regret, that one bolt of the Instrument, as she calls it, must be made of iron by the local smith; but all the other parts are wooden, and may be made at home. The picture makes the design reasonably clear, at least to householders who were accustomed to making their own ropes for work on the land. Presumably, since the seasoning of the rod must take the best part of a year, fishermen then were willing to learn by experiment the right way of twisting a line.

Even Juliana admits that the manufacture of hooks is tricky. Working in metal was no part of the education of a lady, and, though it is easy to bend a red-hot needle into the right shape, the tempering that will give it strength is more difficult. The tools needed - files, tongs, anvil, hammer, etc. - are very small; they may have to be made specially by a skilled smith. For once, in specifying materials she does not begin right at the beginning, with the mining of the ore; probably because at that time first-class steel was not produced in England. The best raw material is osmund, the trade name for bundles of little steel rods imported from the Baltic; or you may cut out one stage and begin with needles of various sizes, from miniature embroidering points to shoemakers' brads. Any handy man or woman should be able to bend the hook, sharpen the point and "raise" the barb at home.

These homemade hooks will have no eyelet at the shank for attachment of the line. Instead, fine silk is bound downwards towards the hook end of the shank; the free end is led through the "hosepipe" formed by the binding and attached to the end of the line. The author notes that the line should always be attached "within the hook," on the barb side of the shank; otherwise the hook will lie crooked under strain.

Except in fishing for pike, where Juliana recommends a copper trace, there is no leader. At the other end the line is tied directly to the rod so that its length cannot be varied.

In the 15th century fly-fishing called for a very high degree of skill. For it was not a matter of persuading a fish to bite, then striking and hauling him in. Juliana expects her pupil to play his fish, if a big one is hooked on a light line, though if you are trying for a particular monster you should use a line strong enough to hold him whatever he may do. Her advice is perfectly sound: "Do not let him get out on your line's end straight from you, but always keep him under the rod so that your line may sustain and bear his leaps and plunges with the help of your crop and of your hand." Of course, if you can do that you can "lead him in the water until he is drowned and overcome." But she does not explain how you set about it.

There follow instructions on when and where to fish, what colour of line to use in different conditions of water, and on tactics in general. Dame Juliana knows that the angler must keep out of sight, and that a shadow on the water is especially frightening. Her advice is the result of careful observation. But it may not be the author's observation; she may be repeating age-old country lore now written down for the first time.

The longest section of the short book is a description of the best bait for float-fishing for every kind of fish, throughout the year. Of course, all bait must be found by the angler, not bought in a shop; and the monthly calendar is needed because certain grubs and larvae can be found only at certain seasons. In this connection Dame Juliana sometimes confuses the two aims of her own fishing. Generally speaking, what she wanted was sport; but she could never forget that a basket of fish, however acquired, would be useful in the refectory. Unattended ground lines - baited hooks lying on the bottom - are still employed by English and Scottish poachers, but there is no more sport in this long-range method of baiting fish than in laying lobster pots in the sea. She devotes a good deal of space to describing the best baits for unattended ground lines.

To make her Treatise complete, she mentions every known method of taking fish without a net, though she has nothing to say of fish weirs except to deplore them as private encroachments on public domain and obstacles to navigation (a complaint as old as Magna Carta and a perennial grievance of the Middle Ages). And just as she feels she ought to begin by proving that fishing is morally more worthy than hunting or hawking, so she feels obliged to deal with every kind of freshwater fish, even those of which she is quite ignorant.

Naturally the salmon has pride of place, though it seems likely from her writings that Dame Juliana has never angled for one. There were none in the little River Ver, though at that time they abounded in the Thames, both at Westminster and Windsor. She has seen salmon taken, but only in the nets of professional fishermen to supply the market. After complaining that salmon lurk very far out in the stream, she recommends various baits for use with a float; but the little detailed touches which make many of her descriptions so vivid are absent. She is repeating what she has been told, not relating her own experiences.

After salmon come trout and grayling, and then all the coarse fish of England - barbel, carp, chub, tench, perch, roach, dace, bleak, ruff, bream, flounder, pike, eel, minnow - whose pursuit is nowadays carried on from little folding stools by placid philosophers who value contemplation more highly than sport. These pastimes need not be treated at further length in this article.

Trout and grayling, usually mentioned together, are the game fish that really gave pleasure to Dame Juliana. She describes more than one method of angling for them. The "ground line lying" and the "ground line running" I take to be two forms of bottom-fishing with a baited hook. Presumably, the lying line was fixed at both ends, with a hook or hooks in the middle; the running line attached at one end only so that the hook moved with the current. Other methods are with a float and baited hook, or, "in leaping time," with an artificial fly.

Baits, of course, vary with the seasons, since they must be freshly gathered. There are several live baits which can be used without a float: minnow, lamprey or frog, the last so mutilated that he cannot swim. The lamprey, recommended as a bait for April, is not the edible fish which was so highly regarded as a delicacy in the Middle Ages, the indigestible luxury that caused the death of King Henry I. Here the author means the Thames lamprey, or "lampern," a little wormlike fish which is now extinct, or nearly so, but which used to be caught in enormous quantities on the Thames between London and Oxford. For human consumption it was sold pickled in barrels, rather like the modern sardine, but it was also sold alive, in large jars, as bait for fishing. In the 18th century lampern were sold by the thousand, and even exported to Holland for use by Dutch fishermen in the North Sea. Overfishing destroyed the stock in the 19th century.

Another live bait, suggested for May, is the stone fly, an insect large and heavy enough to be threaded on a hook. Otherwise, in summer, Juliana recommends some astonishingly cumbrous composite baits. "In August take a flesh fly (blowfly) and the great red worm and bacon fat, and bind them about your hook." If this mass of fodder hit the water near a trout it might stun him even if he did not rise to it. In June another confection is advised, a red worm without its head tied to a codworm.

These baits are made from prey a fish might conceivably find floating naturally in the river. There are others, as artificial as any dressed fly, which must have a long tradition behind them. They could hardly be invented by deliberate thought, and their needless elaboration does not make them more effective than any other fragment of edible matter which may sometimes tempt a hungry fish. A wasp will not be more attractive after being baked in bread and its head coated with dried sheep's blood. The flesh of a cat, flour, beeswax, sheep's tallow and honey, all made up together into a little ball, seems to hint at sympathetic magic rather than first-hand observation of the diet of trout.

At length we come to the most important passage in the book, the earliest description of artificial flies as a lure for trout. There are 12 of them, distributed under the six months from March to August inclusive. They are described as "the" 12 flies, as though the number were already fixed. In the Middle Ages they liked exhaustive lists, and they liked them all the better if they added up to a lucky number. Although artificial, the 12 are intended to represent insects which exist in nature, and to be used when these insects are on the water. And Juliana's flies caught fish. Some of them are still tied today, when her elaborate baits have been forgotten.

These, save for one fly mentioned in ancient history, are the first trout flies recorded in history. I shall not discuss them here; they are the special subject of Part III of this series, where they will be illustrated and discussed in detail.

There follows an illustration, a woodcut showing typical hooks of different sizes. They all look very big, but we must remember that the picture was not drawn by Dame Juliana; the engraver presumably followed her sketch in the manuscript before him, but engraving on wood often enlarges small objects. As a practical guide to making the tackle described in the letterpress, most of the illustrations printed by Wynkyn de Worde are useless.

The Treatise closes with a few paragraphs on sporting etiquette, pointing out especially the wickedness of poaching and of stealing from other men's fish traps. In all, it is less than 10,000 words long.

What can we make of it, as a practical guide to the tying of flies? It is notoriously difficult to put down clear instructions for a manual task, as anyone can see by consulting a cook book. Good cooks write vaguely, because they do not think in precisely measured quantities; writers whose instructions are easy to follow often describe uninteresting dishes.